OpenStack in transition

OpenStack is one of the most important and complex open-source projects you’ve never heard of. It’s a set of tools that allows large enterprises ranging from Comcast and PayPal to stock exchanges and telecom providers to run their own AWS-like cloud services inside their data centers. Only a few years ago, there was a lot of hype around OpenStack as the project went through the usual hype cycle. Now, we’re talking about a stable project that many of the most valuable companies on earth rely on. But this also means the ecosystem around it — and the foundation that shepherds it — is now trying to transition to this next phase.

The OpenStack project was founded by Rackspace and NASA in 2010. Two years later, the growing project moved into the OpenStack Foundation, a nonprofit group that set out to promote the project and help manage the community. When it was founded, OpenStack still had a few competitors, like CloudStack and Eucalyptus. OpenStack, thanks to the backing of major companies and its fast-growing community, quickly became the only game in town, though. With that, community events like the OpenStack Summit started to draw thousands of developers, and with each of its semi-annual releases, the number of contributors to the project has increased.

Now, that growth in contributors has slowed and, as evidenced by the attendance at this week’s Summit in Vancouver.

In the early days, there were also plenty of startups in the ecosystem — and the VC money followed them, together with some of the most lavish conference parties (or “bullshit,” as Canonical founder Mark Shuttleworth called it) that I have experienced. The OpenStack market didn’t materialize quite as fast as many had hoped, though, so some of the early players went out of business, some shut down their OpenStack units and others sold to the remaining players. Today, only a few of the early players remain standing, and the top players are now the likes of Red Hat, Canonical and Rackspace.

And to complicate matters, all of this is happening in the shadow of the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) and the Kubernetes project it manages being in the early stages of the hype cycle.

Meanwhile, the OpenStack Foundation itself is in the middle of its own transition as it looks to bring on other open-source infrastructure projects that are complementary to its overall mission of making open-source infrastructure easier to build and consume.

Unsurprisingly, all of this clouded the mood at the OpenStack Summit this week, but I’m actually not part of the doom and gloom contingent. In my view, what we are seeing here is a mature open-source project that has gone through its ups and downs and now, with all of the froth skimmed off, it’s a tool that provides a critical piece of infrastructure for businesses. Canonical’s Mark Shuttleworth, who created his own bit of drama during his keynote by directly attacking his competitors like Red Hat, told me that low attendance at the conference may not be a bad thing, for example, since the people who are actually in attendance are now just trying to figure out what OpenStack is all about and are all potential customers.

Others echoed a similar sentiment. “I think some of it goes with, to some extent, what’s been building over the last couple of Summits,” Bryan Thompson, Rackspace’s senior director and general manager for OpenStack, said as he summed up what I heard from a number of other vendors at the event. “That is: Is open stack dead? Is this going away? Or is everything just leapfrogging and going straight to Kubernetes on bare metal. And I don’t want to phrase it as ‘it’s a good thing,’ because I think it’s a challenge for the foundation and for the community. But I think it’s actually a positive thing because the core OpenStack services — the core projects — have just matured. We’re not in the early science experiment days of trying to push ahead and scale and grow the core projects, they were actually achieved and people are actually using it.”

That current state produces fewer flashy headlines, but every survey, both from the Foundation itself and third-party analysts, show that the number of users — and their OpenStack clouds — continues to grow. Meanwhile, the Foundation is looking to bring up attendance at its events, too, by adding container and CI/CD tracks, for example.

The company that maybe best exemplifies the ups and downs of OpenStack is Mirantis, a well-funded startup that has weathered the storm by reinventing itself multiple times. Mirantis started as one of the first OpenStack distributions and contributors to the project. During those early days, it raised one of the largest funding rounds in the OpenStack world with a $100 million Series B round, which was quickly followed by another $100 million round in 2015. But by early 2017, Mirantis had pivoted from being a distribution and toward offering managed services for open-source platforms. It also made an early bet on Kubernetes and offered services for that, too. And then this year, it added yet another twist to its corporate story by refocusing its efforts on the Netflix-incubated Spinnaker open-source tool and helping companies build their CI/CD pipelines based on that. In the process, the company shrunk from almost 1,000 employees to 450 today, but as Mirantis CEO and co-founder Boris Renski told me, it’s now cash-flow positive.

So just as the OpenStack Foundation is moving toward CI/CD with its Zuul tool, Mirantis is betting on Spinnaker, which solves some of the same issues, but with an emphasis on integrating multiple code repositories. Renski, it’s worth noting, actually advocated for bringing Spinnaker into the OpenStack foundation (it’s currently managed on a more ad hoc basis by Netflix and Google).

“We need some governance, we need some process,” Renski said. “The [OpenStack] Foundation is known for actually being very good and effectively seeding this kind of formalized, automated and documented governance in open source and the two should work together much closer. I think that Spinnaker should become part of the Foundation. That’s the opportunity and I think it should focus 150 percent of their energy on that before it builds its own thing and before [Spinnaker] goes off to the CNCF as yet another project.”

So what does the Foundation think about all of this? In talking to OpenStack CTO Mark Collier and Executive Director Jonathan Bryce over the last few months, it’s clear that the Foundation knows that change is needed. That process started with opening up the Foundation to other projects, making it more akin to the Linux Foundation, where Linux remains in the name as its flagship project, but where a lot of the energy now comes from projects it helps manage, including the likes of the CNCF and Cloud Foundry. At the Sydney Summit last year, the team told me that part of the mission now is to retask the large OpenStack community to work on these new topics around open infrastructure. This week, that message became clearer.

“Our mission is all about making it easier for people to build and operate open infrastructure,” Bryce told me this week. “And open infrastructure is about operating functioning services based off of open source tool. So open source is not enough. And we’ve been, you know, I think, very, very oriented around a set of open source projects. But in the seven years since we launched, what we’ve seen is people have taken those projects, they’ve turned it into services that are running and then they piled a bunch of other stuff on top of it — and that becomes really difficult to maintain and manage over the long term.” So now, going forward, that part about maintaining these clouds is becoming increasingly important for the project.

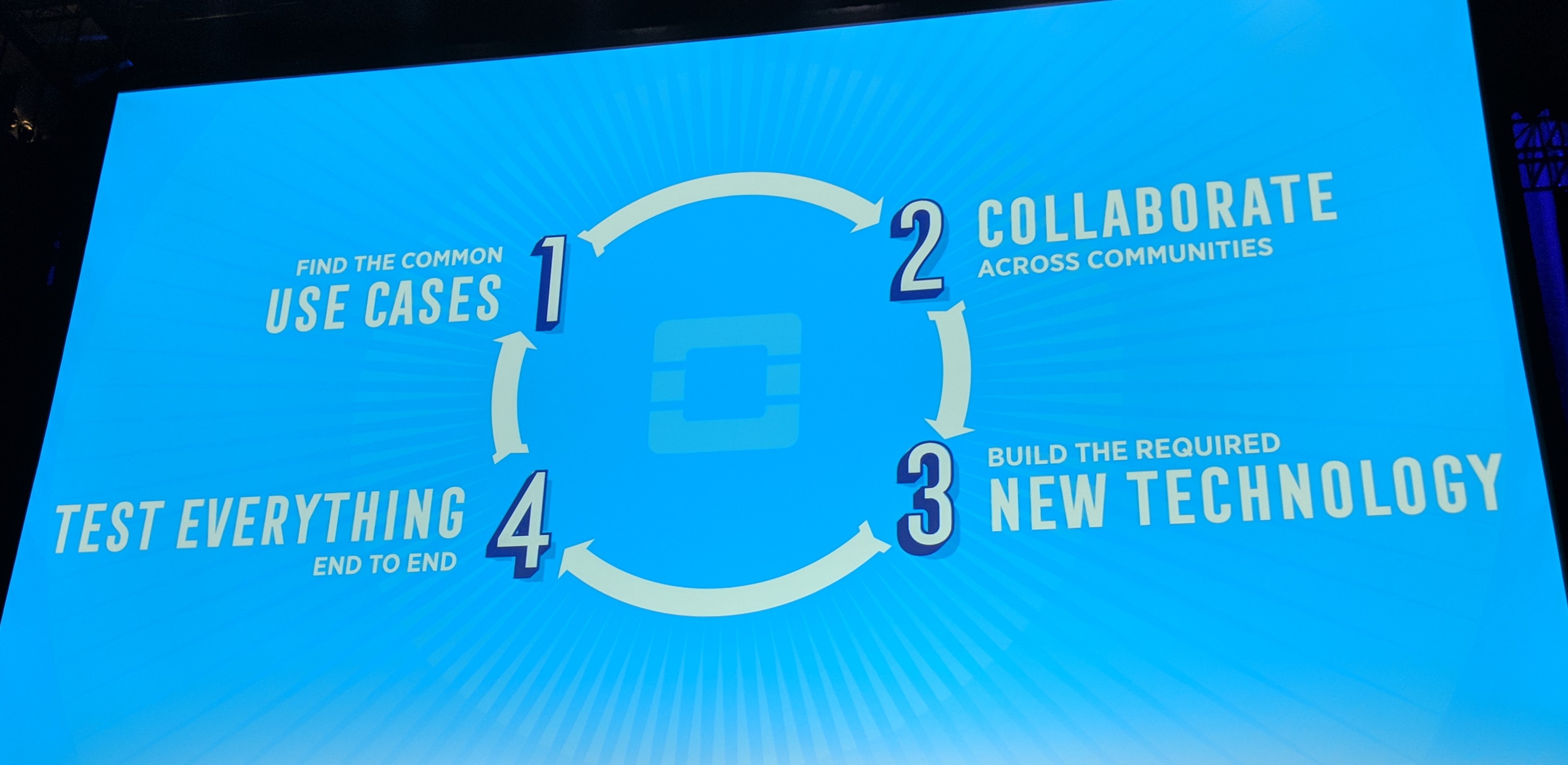

“Open source is not enough,” is an interesting phrase here, because that’s really at the core of the issue at hand. “The best thing about open source is that there’s more of it than ever,” said Bryce. “And it’s also the worst thing. Because the way that most open source communities work is that it’s almost like having silos of developers inside of a company — and then not having them talk to each other, not having them test together, and then expecting to have a coherent, easy to use product come out at the end of the day.”

And Bryce also stressed that projects like OpenStack can’t be only about code. Moving to a cloud-native development model, whether that’s with Kubernetes on top of OpenStack or some other model, is about more than just changing how you release software. It’s also about culture.

“We realized that this was an aspect of the foundation that we were under-prioritizing,” said Bryce. “We focused a lot on the OpenStack projects and the upstream work and all those kinds of things. And we also built an operator community, but I think that thinking about it in broader terms lead us to a realization that we had last year. It’s not just about OpenStack. The things that we have done to make OpenStack more usable apply broadly to these businesses [that use it], because there isn’t a single one that’s only running OpenStack. There’s not a single one of them.”

More and more, the other thing they run, besides their legacy VMware stacks, is containers and specifically containers managed with Kubernetes, of course, and while the OpenStack community first saw containers as a bit of a threat, the Foundation is now looking at more ways to bring those communities together, too.

What about the flagging attendance at the OpenStack events? Bryce and Collier echoed what many of the vendors also noted. “In the past, we had something like 7,000 developers — something insane — but the bulk of the code comes down to about 200 or 300 developers,” said Bryce. Even the somewhat diminished commercial ecosystem doesn’t strike Bryce and Collier as too much of an issue, in part because the Foundation’s finances are closely tied to its membership. And while IBM dropped out as a project sponsor, Tencent took its place.

“There’s the ecosystem side in terms of who’s making a product and selling it to people,” Collier acknowledged. “But for whom is this so critical to their business results that they are going to invest in it. So there’s two sides to that, but in terms of who’s investing in OpenStack and the Foundation and making all the software better, I feel like we’re in a really good place.” He also noted that the Foundation is seeing lots of investment in China right now, so while other regions may be slowing down, others are picking up the slack.

So here is an open-source project in transition — one that has passed through the trough of disillusionment and hit the plateau of productivity, but that is now looking for its next mission. Bryce and Collier admit that they don’t have all the answers, but if there’s one thing that’s clear, it’s that both the OpenStack project and foundation are far from dead.

Powered by WPeMatico