As biological manufacturing moves to the mainstream, Synvitrobio rebrands and raises cash

The pace at which the scientific breakthroughs working to bend the machinery of life to the whims of manufacturing have transformed into real businesses has intensified competition in the biomanufacturing market.

That’s just one reason why Synvitrobio is rebranding as it takes on $2.6 million in new financing to pursue opportunities in biopharmaceutical and biochemical manufacturing. Under its new name, Tierra Biosciences, the company hopes to emphasize its focus on agricultural and biochemical products.

The company is one of several looking to commercialize the field of “cell-free” manufacturing — where biological engineers strip down the cellular building blocks of life to their most basic components to create processes that ideally can be more easily manipulated to produce different kinds of chemicals.

There’s a standard way to create these cell-free processes (described quite nicely in The Economist).

Grab a few quarts of culture with some kind of bacteria, plant or animal cells in it. Then use pressure to force the cells through a valve to break up their membranes and DNA. Give the goo a nice warm environment heated to roughly the average temperature of a human body for about an hour. That activates enzymes that will eat the existing DNA.

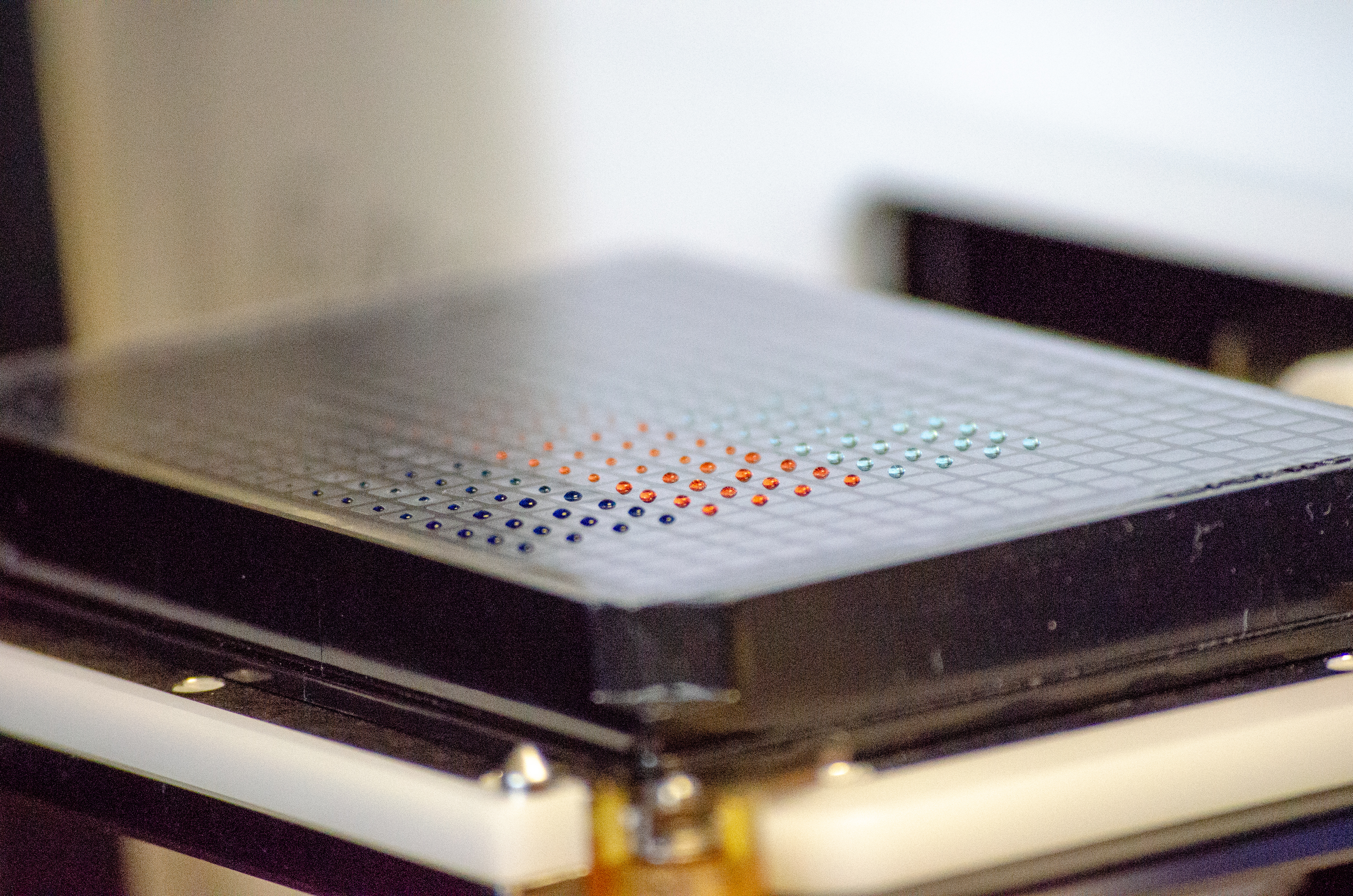

Put all of it in a centrifuge to separate out the ribosomes (which are the important bits). Take those ribosomes and give them a mixture of sugars, amino acids, adenosine triphosphate (the molecular compound that breaks down to provide energy for all biological functions) and new DNA with a different set of instructions on what to make and voila! Micro-factories in a test tube.

Along with co-founders Richard Murray of the California Institute of Technology and George Church, one of the living legends of modern genetics, chief executive officer Zachary Sun designed Tierra to be an engine for new biochemical discovery.

“Everything floats in the cytoplasm… We keep that internal stuff and that allows us to run reactions where a cell wall isn’t necessary. I want to reduce the complex system down to its component parts,” says Sun. “We look at this as a data collection problem. We want to use cell-free to tell you what to put either in a cell or in cell-free systems… We can collect more data faster using our cell-free system.”

The startup is already working with the Department of Energy research institution at Oak Ridge National Laboratory to develop processes to create vanillin (vanilla extract) and mevalonate (turpentine) from biomass.

It’s an approach that is already showing the potential for investment returns in life sciences and pharmaceuticals. For inspiration, Tierra can look to the South San Francisco-based Sutro Biopharma.

That company has signed a drug discovery agreement with Merck to develop new immune-modulating therapies (that bring the immune system into check) for cancer and auto-immune disorders, in a deal worth up to $1.6 billion if the company hits certain milestones — in addition to a $60 million upfront payment. Sutro raised more than $85 million in new funding in July (from investors including Merck) and just filed to go public on the Nasdaq.

According to Sun, the newly named Tierra has its own partnerships with global 2,000 companies in the works. “We’re looking to scale those commitments. We see the application space as being this natural products environment,” he says.

There’re multiple avenues to pursue, with the technology widely applicable to everything from pesticides to pharmaceuticals, flavorings and even energy.

Cyclotron Road team photos. 2016. Zachary Sun.

“Synthetic biology at its core is about applying engineering best practices to speed up the ‘design-build-test’ cycles in the reprogramming of existing or construction of new biological systems. By component-izing and modularizing the cell they can radically increase the speed of those cycles,” says Seth Bannon, a co-founder of the venture capital firm Fifty Years, which invests in startups commercializing “frontier” science.

For the investors, entrepreneurs and reporters who witnessed the birth of the cleantech bubble a decade ago and then tracked its implosion in subsequent years, the excitement this kind of technology elicits is another of history’s rhymes.

Technologies like Tierra’s aren’t new. San Diego-based Genomatica has been working on biological manufacturing for the past 18 years. The company is now exploring a cell-free system to grow chemicals that are used in the manufacture of materials like Lycra. Since 2008, Medford, Mass.-based GreenLight Biosciences has been working to bring its own biologically based zero-calorie sugar substitute to market.

What may be different now is the maturity of the technologies that are being commercialized and the perspective of the startups coming to market — who have the benefit of avoiding the missteps made by an earlier generation.

Investors led by Social Capital with participation from Fifty Years, KdT Ventures and angel investors seem to see a difference in these companies. And large research institutions are also marshaling resources to support the vision laid out by Sun, Murray and Church. DARPA, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Energy, Cyclotron Road and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the National Science Foundation and the Gates Foundation have all backed the company, as well.

“So many therapeutic molecules come from nature. As the DNA of plants, animals and microbes is read in exponentially increasing volume, we expect to find useful and game-changing chemistry encoded by it. Tierra’s platform will allow us to look for molecules which might otherwise be buried in the complexity of cells’ metabolism,” says Louis Metzger, chief scientific officer of Tierra, who comes from a background of drug discovery.

Powered by WPeMatico