WeWork files confidentially for IPO

WeWork, the co-working giant now known as The We Company, has submitted confidential documents to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for an initial public offering, the company confirmed in a press release Monday.

According to The New York Times, the business initially filed IPO paperwork in December.

WeWork, valued at $47 billion in January, has raised $8.4 billion in a combination of debt and equity funding since it was founded by Adam Neumann and Miguel McKelvey in 2010. WeWork is among several tech unicorns with hundreds of millions, billions actually, in backing from the SoftBank Vision Fund. Recently, the Japanese telecom giant eyed a majority stake in the company worth $16 billion, but cooled their jets at the last minute.

WeWork doubled its revenue from $886 million in 2017 to roughly $1.8 billion in 2018, with net losses hitting a staggering $1.9 billion. These aren’t attractive metrics for a pre-IPO business; then again, Uber’s currently completing a closely watched IPO roadshow despite shrinking growth. Here’s more from Crunchbase News on WeWork’s top line financials:

- WeWork’s 2017 revenue: $886 million

- WeWork’s 2017 net loss: $933 million

- WeWorks 2018 revenue: $1.82 billion (+105.4 percent)

- WeWork’s 2018 net loss: $1.9 billion (+103.6 percent)

On the bright side, per Axios, WeWork established a 90 percent occupancy rate in 2018, with total membership rising 116 percent to 401,000.

WeWork is often referenced as the perfect example of Silicon Valley’s tendency to inflate valuations. WeWork, a real estate business, burns through cash rapidly and will undoubtedly have to work hard to convince public markets investors of its longevity, as well as its status as a tech company.

WeWork is backed by SoftBank, Benchmark, T. Rowe Price, Fidelity, Goldman Sachs and several others.

Powered by WPeMatico

Pana raises $10 million to help companies arrange travel for onsite interviews

Your last 10 emails with a recruiter before an onsite interview probably shouldn’t be about rebooking your canceled flight.

Pana is a Denver startup now setting its sights on the corporate travel market, with a specific eye towards killing the back-and-forth email or spreadsheet coordination. The startup, founded in 2015, first tried to gain an inroad with consumers, but its $49 per month individual-focused travel concierge plan probably limited its reach.

The company’s latest shot at taking on corporate travel lets companies use the service to outsource dealing with out-of-network “guests.” The startup is looking to take this path as an inroad into the broader corporate travel market, and is making the apparent choice to work with more expansive corporate travel companies like SAP’s Concur rather than against them, initially at least.

The company just closed a $10 million Series A round led by Bessemer Venture Partners with participation from Techstars, Matchstick Ventures, and MergeLane Fund. Previous investors also include 500 Startups, FG Angels and The Galvanize Fund.

Pana is already booking thousands of trips per month for companies using the service to coordinate business travel for interviewees. Rather than leaving recruiters to the arduous process of back-and-forth messaging to hammer out initial details, Pana takes care of it through an omni-channel mesh of automation and human concierge in-app chat, text or email.

“A key piece of the value proposition is that if you do ask something complex, we’re going to instantly connect you to a human agent,” founder Devon Tivona told TechCrunch in an interview. “When it does go to a person, we have a five-minute response time.”

Getting a flight booked for someone outside the company directory can be challenging enough, but with travel, everything grows infinitely more complex the second that something goes awry. In addition to functioning as a tool for coordination, the startup’s team of assistants are there to help re-book flights or re-arrange travel if everything doesn’t go according to plan.

Even if Pana is working with the big corporate travel agencies today, its investors are banking on the startup accomplishing what the giants can’t at their scale.

“…Whenever a really large incumbent, particularly in software gets acquired, and I’m thinking about when SAP acquired Concur five or so years ago, it creates this massive innovation gap that allows, I’d say, new startups to really reinvent the status quo,” Bessemer partner Kristina Shen told TechCrunch in an interview.

Pana’s current customers include Logitech, Quora and Shopify, among others.

Powered by WPeMatico

Caribou Biosciences CEO, Rachel Haurwitz will talk CRISPR’s present and future applications at DisruptSF

Seven years ago, Rachel Haurwitz finished her last day as a student in the University of California laboratory where she helped conduct some of the pioneering research on the gene editing technology known as CRISPR, and became employee number one at Caribou Biosciences, a company founded to commercialize that research.

In those seven years, the market for CRISPR applications has grown tremendously and Caribou Biosciences is at the forefront of the companies propelling it forward.

Which is why we’re absolutely thrilled to have Haurwitz join us on stage at Disrupt SF 2019.

Haurwitz studied under Caribou Biosciences’ co-founder Jennifer Doudna — one of the scientists who discovered CRISPR’s gene editing applications — and Caribou was formed to be the conduit through which the groundbreaking research from the Berkeley lab would become products that companies could use.

Short for “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats”, CRISPR works by targeting certain sequences of DNA — the genetic instructions for the development and reproduction of all organisms — and then binding them to an enzyme that cuts the specific sequence.

Once edited, researchers can add or simply delete pieces of genetic material, or change the DNA by replacing a segment with customized code designed to achieve specific functions.

There are few industries that CRISPR doesn’t have the power to transform. Already, Caribou Biosciences technology is being used at Intellia, which is developing therapies based on CRISPR technologies (Haurwitz is a co-founder). And that’s just the beginning.

Caribou’s chief executive thinks of her company as a platform for developing technologies in therapeutics, research, agriculture and industrial biology.

Already, CRISPR technologies are being used to biologically manufacture chemicals, replace pesticides and fertilizers, and provide cures for rare diseases once though impossible.

“Any market with bio-based products will be changed by gene editing,” Haurwitz has said.

At SF Disrupt Haurwitz will talk about the implications of that transformation, and what’s ahead for the company that’s leading the charge in this genetic revolution.

Tickets are available here.

Powered by WPeMatico

Mirantis makes configuring on-premises clouds easier

Mirantis, the company you may still remember as one of the biggest players in the early days of OpenStack, launched an interesting new hosted SaaS service today that makes it easier for enterprises to build and deploy their on-premises clouds. The new Mirantis Model Designer, which is available for free, lets operators easily customize their clouds — starting with OpenStack clouds next month and Kubernetes clusters in the coming months — and build the configurations to deploy them.

Typically, doing so involves writing lots of YAML files by hand, something that’s error-prone and few developers love. Yet that’s exactly what’s at the core of the infrastructure-as-code model. Model Designer, on the other hand, takes what Mirantis learned from its highly popular Fuel installer for OpenStack and takes it a step further. The Model Designer, which Mirantis co-founder and CMO Boris Renski demoed for me ahead of today’s announcement, presents users with a GUI interface that walks them through the configuration steps. What’s smart here is that every step has a difficulty level (modeled after Doom’s levels, ranging from “I’m too young to die” to “ultraviolence” — though it’s missing Dooms “nightmare” setting), which you can choose based on how much you want to customize the setting.

Typically, doing so involves writing lots of YAML files by hand, something that’s error-prone and few developers love. Yet that’s exactly what’s at the core of the infrastructure-as-code model. Model Designer, on the other hand, takes what Mirantis learned from its highly popular Fuel installer for OpenStack and takes it a step further. The Model Designer, which Mirantis co-founder and CMO Boris Renski demoed for me ahead of today’s announcement, presents users with a GUI interface that walks them through the configuration steps. What’s smart here is that every step has a difficulty level (modeled after Doom’s levels, ranging from “I’m too young to die” to “ultraviolence” — though it’s missing Dooms “nightmare” setting), which you can choose based on how much you want to customize the setting.

Model Designer is an opinionated tool, but it does give users quite a bit of freedom, too. Once the configuration step is done, Mirantis actually takes the settings and runs them through its Jenkins automation server to validate the configuration. As Renski pointed out, that step can’t take into account all of the idiosyncrasies of every platform, but it can ensure that the files are correct. After this, the tool provides the user with the configuration files, and actually deploying the OpenStack cloud is then simply a matter of taking the files, together with the core binaries that Mirantis makes available for download, to the on-premises cloud and executing a command-line script. Ideally, that’s all there is to the process. At this point, Mirantis’ DriveTrain tools take over and provision the cloud. For upgrades, users simply have to repeat the process.

Mirantis’ monetization strategy is to offer support, which ranges from basic support to fully managing a customer’s cloud. Model Designer is yet another way for the company to make more users aware of itself and then offer them support as they start using more of the company’s tools.

Powered by WPeMatico

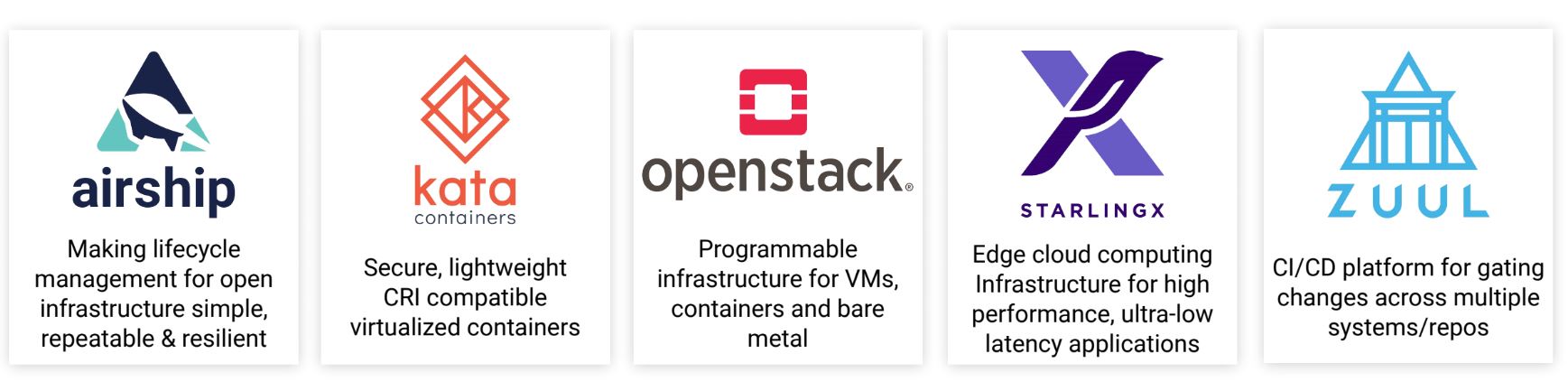

With Kata Containers and Zuul, OpenStack graduates its first infrastructure projects

Over the course of the last year and a half, the OpenStack Foundation made the switch from purely focusing on the core OpenStack project to opening itself up to other infrastructure-related projects as well. The first two of these projects, Kata Containers and the Zuul project gating system, have now exited their pilot phase and have become the first top-level Open Infrastructure Projects at the OpenStack Foundation.

The Foundation made the announcement at its Open Infrastructure Summit (previously known as the OpenStack Summit) in Denver today after the organization’s board voted to graduate them ahead of this week’s conference. “It’s an awesome milestone for the projects themselves,” OpenStack Foundation executive direction Jonathan Bryce told me. “It’s a validation of the fact that in the last 18 months, they have created sustainable and productive communities.”

It’s also a milestone for the OpenStack Foundation itself, though, which is still in the process of reinventing itself in many ways. It can now point at two successful projects that are under its stewardship, which will surely help it as it goes out and tries to attract others who are looking to bring their open-source projects under the aegis of a foundation.

In addition to graduating these first two projects, Airship — a collection of open-source tools for provisioning private clouds that is currently a pilot project — hit version 1.0 today. “Airship originated within AT&T,” Bryce said. “They built it from their need to bring a bunch of open-source tools together to deliver on their use case. And that’s why, from the beginning, it’s been really well-aligned with what we would love to see more of in the open-source world and why we’ve been super excited to be able to support their efforts there.”

With Airship, developers use YAML documents to describe what the final environment should look like and the result of that is a production-ready Kubernetes cluster that was deployed by OpenStack’s Helm tool — though without any other dependencies on OpenStack.

AT&T’s assistant vice president, Network Cloud Software Engineering, Ryan van Wyk, told me that a lot of enterprises want to use certain open-source components, but that the interplay between them is often difficult and that while it’s relatively easy to manage the life cycle of a single tool, it’s hard to do so when you bring in multiple open-source tools, all with their own life cycles. “What we found over the last five years working in this space is that you can go and get all the different open-source solutions that you need,” he said. “But then the operator has to invest a lot of engineering time and build extensions and wrappers and perhaps some orchestration to manage the life cycle of the various pieces of software required to deliver the infrastructure.”

It’s worth noting that nothing about Airship is specific to the telco world, though it’s no secret that OpenStack is quite popular in the telco world and unsurprisingly, the Foundation is using this week’s event to highlight the OpenStack project’s role in the upcoming 5G rollouts of various carriers.

In addition, the event will showcase OpenStack’s bare-metal capabilities, an area the project has also focused on in recent releases. Indeed, the Foundation today announced that its bare-metal tools now manage more than a million cores of compute. To codify these efforts, the Foundation also today launched the OpenStack Ironic Bare Metal program, which brings together some of the project’s biggest users, like Verizon Media (home of TechCrunch, though we don’t run on the Verizon cloud), 99Cloud, China Mobile, China Telecom, China Unicom, Mirantis, OVH, Red Hat, SUSE, Vexxhost and ZTE.

Powered by WPeMatico

FutureLearn takes $65M from Seek Group for 50% stake in UK online degree platform

Edtech and recruitment continue to converge. London-based online degree platform, FutureLearn, is taking £50 million (~$64.6M) from Australian-based online job matching group, Seek, in exchange for a 50 per cent stake in the business — just days after the same group led a massive Series E in U.S. online learning giant Coursera.

U.K. distance learning veteran, the Open University — which had wholly owned the FutureLearn platform up til now — retains a 50 per cent stake in the business following the Seek Group investment.

In a press release announcing the news, FutureLearn said the investment values it at £100M ($129M) — some six years after the initiative was first announced, with the OU bringing together a consortium of U.K. universities to attack the MOOCs/online learning space which was then being rapidly expanded by U.S. edtech startups.

“Our partnership with Seek and the investment in FutureLearn will take our unique mission to make education open for all into new parts of the world. Education improves lives, communities and economies and is a truly global product, with no tariffs on ideas,” said OU vice chancellor Mary Kellett in a statement on the investment.

The joint venture will have “contractual arrangements” to protect its academic independence, teaching methods and curriculum, the OU added — in an attempt to assuage concerns about an (overly) commercially minded takeover of its fledgling digital education platform.

The first FutureLearn courses launched in fall 2013. Since then a cumulative total of nine million+ people have signed up to learn via its platform — which now offers around 2,000 courses in all.

This includes short courses; postgraduate diplomas and certificates; all the way up to fully online degrees. (FutureLearn partners with six U.K. universities on the full degree courses at this stage.)

FutureLearn also has partnerships with management consultancy firm Accenture; the British Council; the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development; learn-to-code foundation Raspberry Pi; and Health Education England (part of the UK’s National Health Service); and is involved in U.K. government-backed initiatives to address skills gaps — including The Institute of Coding and the National Centre for Computing Education.

Last fall the Financial Times reported that the OU was looking for a £40M capital injection for FutureLearn to fund more courses and better compete with the scale of U.S. edtech giants — like Coursera and Lynda.com.

It’s not clear how many more courses FutureLearn plans to add with its new partner on board; a spokesperson told us it is not able to provide a figure at this stage.

For a little comparative context, some 40M people have taken online classes via Coursera to date — with that platform currently offering some 3,200 courses, and partnering with the likes of Columbia University, Johns Hopkins and the University of Michigan. While Coursera’s $103M in Series E reportedly valued its business at well over a $1BN, with Seek coming on board as a strategic investor.

The shared investor is an interesting but perhaps not surprising development given the different markets involved, and the challenge of monetizing free-to-access courses without having massive scale — suggesting the Seek group, which is already well established across Australia, New Zealand, China, South East Asia, Brazil and Mexico — sees more opportunities from strengthening regional online learning platform plays, in Europe and the U.S., to grow the overall online learning pipe and expand adjacent cross-marketing options in employment/job matching.

Last week, when its strategic investment in Coursera was announced, the Seek group talked effusively about how edtech platforms enabling up-skilling and re-skilling are “aligned” with its employment-focused business mission. (Or “our purpose of helping people live fulfilling working lives”, as it put it.)

The FutureLearn partnership provides Seek with access to another pool of potential job seekers — including actively engaged learners in the UK/Europe — to further grow the geographical reach of its recruitment platform.

Commenting on the investment in a statement, Seek co-founder and CEO Andrew Bassat said: “Technology is increasing the accessibility of quality education and can help millions of people up-skill and re-skill to adapt to rapidly changing labour markets. We see FutureLearn as a key enabler for education at scale.”

“FutureLearn’s reputation is strong and it has attracted leading education providers onto its platform. We are excited to come on as a partner with The Open University,” he added.

FutureLearn’s CEO Simon Nelson said the joint venture will allow the learning platform to extend its global reach and impact.

“This investment allows us to focus on developing more great courses and qualifications that both learners and employers will value,” he said in a statement. “This includes building a portfolio of micro-credentials and broadening our range of flexible, fully online degrees and being able to enhance support for our growing number of international partners to empower them to build credible digital strategies, and in doing so, transform access to education.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Tray.io hauls in $37 million Series B to keep expanding enterprise automation tool

Tray.io, the startup that wants to put automated workflows within reach of line of business users, announced a $37 million Series B investment today.

Spark Capital led the round with help from Meritech Capital, along with existing investors GGV Capital, True Ventures and Mosaic Ventures. Under the terms of the deal Spark’s Alex Clayton will be joining the Tray’s board of directors. The company has now raised over $59 million.

Rich Waldron, CEO at Tray, says the company looked around at the automation space and saw tools designed for engineers and IT pros and wanted to build something for less technical business users.

“We set about building a visual platform that would enable folks to essentially become programmers without needing to have an engineering background, and enabling them to be able to build out automation for their day-to-day role.”

He added, “As a result, we now have a service that can be used in departments across an organization, including IT, whereby they can build extremely powerful and flexible workflows that gather data from all these disparate sources, and carry out automation as per their desire.”

Alex Clayton from lead investor Spark Capital sees Tray filling in a big need in the automation space in a spot between high end tools like Mulesoft, which Salesforce bought last year for $6.5 billion, and simpler tools like Zapier. The problem, he says, is that there’s a huge shortage of time and resources to manage and really integrate all these different SaaS applications companies are using today to work together.

“So you really need something like Tray because the problem with the current Status Quo [particularly] in marketing sales operations, is that they don’t have the time or the resources to staff engineering for building integrations on disparate or bespoke applications or workflows,” he said.

Tray is a seven year old company, but started slowly taking the first 4 years to build out the product. They got $14 million Series A 12 months ago and have been taking off ever since. The company’s annual recurring revenue (ARR) is growing over 450 percent year over year with customers growing by 400 percent, according to data from the company. It already has over 200 customers including Lyft, Intercom, IBM and SAP.

The company’s R&D operation is in London, with headquarters in San Francisco. It currently has 85 employees, but expects to have 100 by the end of the quarter as it begins to put the investment to work.

Powered by WPeMatico

‘The Division 2’ is the brain-dead, antipolitical, gun-mongering vigilante simulator we deserve

In The Division 2, the answer to every question is a bullet. That’s not unique in the pervasively violent world of gaming, but in an environment drawn from the life and richly decorated with plausible human cost and cruelty, it seems a shame; and in a real world where plentiful assault rifles and government hit squads are the problems, not the solutions, this particular power fantasy feels backwards and cowardly.

Ubisoft’s meticulous avoidance of the real world except for physical likeness was meant to maximize its market and avoid the type of “controversy” that brings furious tweets and ineffectual boycotts down on media that dare to make statements. But the result is a game that panders to “good guy with a gun” advocates, NRA members, everyday carry die-hards, and those who dream of spilling the blood of unsavory interlopers and false patriots upon this great country’s soil.

There are two caveats: That we shouldn’t have expected anything else, from Ubisoft or anyone; and that it’s a pretty good game if you ignore all that stuff. But it’s getting harder to accept every day, and the excuses for game studios are getting fewer. (Some spoilers ahead, but trust me, it doesn’t matter.)

To put us all on the same page: The Division 2 (properly Tom Clancy’s The Division 2, which just about sums it up right there) is the latest “game as a service” to hit the block, aspiring less towards the bubblegum ubiquity of Fortnite and than the endless grind of a Destiny 2 or Diablo 3. The less said about Anthem, the better (except Jason Schrier’s great report, of course).

It’s published by Ubisoft, a global gaming power known for creating expansive gaming worlds (like the astonishingly beautiful Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey) with bafflingly uneven gameplay and writing (like the astonishingly lopsided Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey).

So it was perhaps to be expected that The Division 2 would be heavy on atmosphere and light on subtlety. But I didn’t expect to be told to see the President snatch a machine gun from his captors and mow them down — then tell your character that sometimes you can’t do what’s popular, you have to do what’s necessary.

It would be too much even if the game was a parody and not, as it in fact is, deeply and strangely earnest. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

EDC Simulator 2

The game is set in Washington, D.C.; its predecessor was in New York. Both were, like most U.S. cities in this fictitious near future, devastated by a biological attack on Black Friday that used money as a vector for a lethal virus. That’s a great idea, perhaps not practical (who pays in cash?), but a clever mashup of terrorist plots with consumerism. (The writing in the first Division was considerably better than this one.)

Your character is part of a group of sleeper agents seeded throughout the country, intended to activate in the event of a national emergency, surviving and operating on your own or with a handful of others, procuring equipment and supplies on the go, taking out the bad guys and saving the remaining civilians while authority reasserts itself.

You can see how this sets up a great game: exploring the ruins of a major city, shooing out villains, and upgrading your gear as you work your way up the ladder.

And in a way it does make a great game. If you consider the bad guys just types of human-shaped monsters, your various guns and equipment the equivalent of new swords and wands, breastplates and greaves, with your drones and tactical launchers modern spells and auras, it’s really quite a lot like Diablo, the progenitor of the “looter” genre.

And in a way it does make a great game. If you consider the bad guys just types of human-shaped monsters, your various guns and equipment the equivalent of new swords and wands, breastplates and greaves, with your drones and tactical launchers modern spells and auras, it’s really quite a lot like Diablo, the progenitor of the “looter” genre.

Moment to moment gameplay has you hiding behind cover, popping out to snap off a few shots at the bad guys, who are usually doing the same thing 10 or 20 yards away, but generally not as well as you. Move on to the next room or intersection, do it again with some more guys, rinse and repeat. It sounds monotonous, and it is, but so is baseball. People like it anyway. (I’d like to give a shout-out to the simple, effective multiplayer that let me join a friend in seconds.)

But the problem with The Division 2 isn’t its gameplay, although I could waste your time (instead) with some nitpicking of the damage systems, the mobs, the inventory screen, and so on. The problem with The Division 2 isn’t even that it venerates guns. Practically every game venerates guns, because as Tim Rogers memorably paraphrased CliffyB once: “games are power fantasies — and it’s easy to make power fantasies, because guns are so powerful, and raycasting is simple, and raycasting is like a gun.” It’s difficult to avoid.

No, the problem with The Division 2 is the breathtaking incongruity between the powerfully visualized human tragedy your character inhabits and the refusal to engage even in an elementary way with the themes to which it is inherently tied: terrorism, guns, government and anti-government forces, and everything else. It’s exploitative, cynical, and absurd.

The Washington, D.C. of the game is a truly amazing setting. Painstakingly detailed block by block and containing many of the most notable landmarks of the area, it’s a very interesting game world to explore, even more so I imagine if you are from there or are otherwise familiar with the city.

The Washington, D.C. of the game is a truly amazing setting. Painstakingly detailed block by block and containing many of the most notable landmarks of the area, it’s a very interesting game world to explore, even more so I imagine if you are from there or are otherwise familiar with the city.

The marks of a civilization-ending disaster are everywhere. Abandoned cars and security posts with vines and grass creeping up between them, broken and boarded up windows and doors, left luggage and improvised camping spots. Real places form the basis for thrilling setpiece shootouts: museums, famous offices, the White House itself (which you find under limp siege in the first mission). This is a fantasy very much based in reality — but only on the surface. In fact all this incredibly detailed scenery is nothing more than cover for shootouts.

I can’t tell you how many times my friend and I traversed intricately detailed monuments, halls, and other environments, marveling at the realism with which they were decorated (though perhaps there were a few too many gas cans), remarking to one another: “Damn, this place is insane. I can’t believe they made it this detailed just to have us do the same exact combat encounter as the entire rest of the game. How come nobody is talking about the history of this place, or the bodies, or the culture here?”

When fantasy isn’t

Now, to be clear, I don’t expect Ubisoft to make a game where you learn facts about helicopters while you shoot your way through the Air and Space Museum, or where you engage in philosophical conversation with the head of a band of marauders rather than lob grenades and corrosive goo in their general direction. (I kind of like both those ideas, though.)

But the dedication with which the company has avoided any kind of reality whatsoever is troubling.

We live in a time when people are taking what they call justice into their own hands by shooting others with weapons intended for warfare; when paramilitary groups are defending their strongholds with deadly force; when biological agents are being deployed against citizenry; when governments are surveilling and tracking people via controversial AI systems; when the leaders of that government are making unpopular and ethically fraught decisions without the knowledge of their constituency.

This game enthusiastically endorses all of the previous ideas with the naive justification that you’re the good guys. Of course you’re the good guys — everyone claims they’re the good guys! But objectively speaking, you’re a secret government hit squad killing whoever you’re told to, primarily other citizens. Ironically, despite being called an agent, you have no agency — you are a walking gun doing the bidding of a government that has almost entirely dissolved. What could possibly go wrong? The Division 2 certainly makes no effort to explore this.

The superficiality of the story I could excuse if it didn’t rely so strongly on using the real world as set dressing for its paramilitary dress-up-doll fantasy.

Basing your game in a real world location is, I think, a fabulous idea. But in doing so, especially if as part of the process you imply the death of millions, a developer incurs a responsibility to do more than use that location as level geometry.

The Division 2 instead uses these deaths and the most important places in D.C. literally as props. Nothing you do ever has anything to do with what the place is except in the loosest way. While you visit morgues and improvised mass graves piled with body bags, you never see anyone dead or dying… unless you kill them.

It’s hard to explain what I find so distasteful about this. It’s a combination of the obvious emphasis on the death of innocents, in a brute-force attempt to create emotional and political relevance, with the utterly vacuous violence you fill that world with. It feels disrespectful to itself, to the setting, to set a piece of media so incredibly dumb and mute in a disaster so credible and relevant.

This was a deliberate decision, to rob the game of any relevance — a marketing decision. To destroy D.C. — that sells. To write a story or design gameplay that in any way reflects why that destruction resonates — that doesn’t sell. “We cannot be openly political in our games,” said Alf Condelius, the COO of the studio that created the game, in a talk before the game’s release. Doing so, he said, would be “bad for business, unfortunately, if you want the honest truth.” I can’t be the only one who feels this to be a cop-out of pretty grand proportions, with the truth riding on its coattails.

This was a deliberate decision, to rob the game of any relevance — a marketing decision. To destroy D.C. — that sells. To write a story or design gameplay that in any way reflects why that destruction resonates — that doesn’t sell. “We cannot be openly political in our games,” said Alf Condelius, the COO of the studio that created the game, in a talk before the game’s release. Doing so, he said, would be “bad for business, unfortunately, if you want the honest truth.” I can’t be the only one who feels this to be a cop-out of pretty grand proportions, with the truth riding on its coattails.

Perhaps you think I’m holding game developers to an unreasonable standard. But I believe they are refusing to raise the bar themselves when they easily could and should. The level of detail in the world is amazing, and it was clearly designed by people who understand what could happen should disaster strike. The bodies piled in labs, the desolation of a city overtaken by nature, the perfect reproductions of landmarks — an enormous amount of effort and money was put into this part of the game.

On the other hand, it’s incredibly obvious from the get-go that very, very little attention was paid to the story and characters, the dialogue, the actual choices you can make as a player (there are none to speak of). There is no way to interact with people except to shoot them, or for them to tell you who to shoot. There is no mention of politics, of parties, of race or religion. I feel sure more time was spent modeling the guns — which, by the way, are real licensed models — than the main “characters,” though it must have been time-consuming to so completely to purge those characters of any ideas or opinions that could possibly reflect the real world.

One tragedy please, hold the relevance

This is deliberate. There’s no way this could have happened unless Ubisoft, from the start, made it clear that the game was to be divorced from the real world in every way except those that were deemed marketable.

That this is what they considerable marketable is a sad sort of indictment of the people they are selling this game to. The prospect of inserting oneself into a sort of justified vigilante role where you rain hot righteous lead on these generic villains trampling our great flag seems to be a special catnip concoction Ubisoft thought would appeal to millions — millions who (or more importantly, whose wallets) might be chilled by the idea of a story that actually takes on the societal issues that would be at play in a disaster like this one. We got the game we deserved, I suppose.

Say what you will about the narrative quality of campaigns of Call of Duty and Battlefield, but they at least attempt to engage with the content they are exploiting to sell the game. World War II is marketable because it’s the worst thing that ever happened and destroyed the lives of millions in a violent and dramatic way. Imagine building a photorealistic reproduction of wartime Stalingrad, or Paris, or Berlin, and then filling it not with Axis and Allied forces but simplified and palatable goodies and baddies with no particular ethos or history.

I certainly don’t mean to equate the theoretical destruction of D.C. with the Holocaust and WWII, but as perhaps the most popular period and venue for shooters like this, it’s the obvious comparison to make thematically, and what one finds is that however poor the story of a given WWII game, it inevitably attempts to emphasize and grapple with the enormity of the events you are experiencing. That’s the kind of responsibility I think you take on when you illustrate your game with the real world — even a fantasy version of the real world.

Furthermore Ubisoft has accepted that it must take some political stances, such as the inclusion of same-sex player-NPC relationships in Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey — not controversial to me and many others, certainly, but hardly an apolitical inclusion in the present global political landscape. (I applaud them for this, by the way, and many others have as well.) It’s arguable this is not “overt” in that Kassandra and Alexios don’t break the first wall to advocate for marriage equality, but I think it is deliberately and unapologetically espousing a stance on a politically and societally charged issue.

It seems it is not that the company cannot be overtly political, but that it decided in this case that to be political on issues of guns, the military, terrorism, and so on was too much of a risk. To me that is in itself a political choice.

I do think Ubisoft is a fantastic company and makes wonderful games — but I also think the decision to completely divorce a game with fundamentally political underpinnings from the real politics and humanitarian conditions that empower it is a sad and spineless decision that makes them look both avaricious and inhumane. I know they can do better because others already have and do.

The Division 2 is a good game as far as games go. But games, like movies, TV, and other media, are very much art now, deserving of criticism as to their ideas as well as their controls and graphics; and as art, The Division 2 is as much a barren wasteland scoured of humanity as the D.C. it depicts.

Powered by WPeMatico

How a blockchain startup with 1M users is working to break your Google habit

The antitrust argument that says big tech needs breaking up to stop platforms abusing competition and consumers in a two-faced role as seller and (manipulative) marketplace may only just be getting going on a mainstream political stage — but startups have been at the coal face of the fight against crushing platform power for years.

Presearch, a 2017-founded, pro-privacy blockchain-based startup that’s using cryptocurrency tokens as an incentive to decentralize search — and thereby (it hopes) loosen Google’s grip on what Internet users find and experience — was born out of the frustration, almost a decade before, of trying to build a local listing business only to have its efforts downranked by Google.

That business, Silicon Valley-based ShopCity.com, was founded in 2008 and offers local business search on Google’s home turf — operating sites like ShopPaloAlto.com and ShopMountainView.com — intended to promote local businesses by making them easier to find online.

But back in 2011 ShopCity complained publicly that Google’s search ranking systems were judging its content ‘low quality’ and relegating its listings pages to the unread deeps of search results. Listings which, nonetheless, had backing and buy in from city governments, business associations and local newspapers.

ShopCity went on to complain to the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), arguing Google was unfairly favoring its own local search products.

Going public with its complaint brought it into contact with sceptical segments of the tech press more accustomed to cheerleading Google’s rise than questioning the agency of its algorithms.

“We have developed a very comprehensive and holistic platform for community commerce, and that is why companies like The Buffalo News, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, have partnered up with us and paid substantial licensing fees to use our system,” wrote ShopCity co-founder Colin Pape, responding to a dismissive Gigaom article in November 2011 by trying to engage the author in comments below the fold.

“The fact that Google recently began copying our multi-domain model… and our in-community approach, is a good indication that we are onto something and not just a ‘two-bit upstart’,” Pape went on. “Google has stated that the local space is of great importance to them… so they definitely have a motive to hinder others from becoming leaders, and if all it takes to stop a competitor from developing is a quick tweak to a domain profile, then why not?”

While the FTC went on to clear Google of anti-competitive behavior in the ShopCity case, Europe’s antitrust authorities have taken a very different view about Mountain View’s algorithmic influence: The EU fined Google $2.73BN in 2017 after a lengthy investigations into its search comparison service which found, in a scenario similar to ShopCity’s contention, Google had demoted rival product search services and promoted its own competing comparison search product.

That decision was the first of a trio of multibillion EU fines for Google: A record-breaking $5BN fine for Android antitrust violations fast-followed in 2018. Earlier this year Google was stung a further $1.7BN for anti-competitive behavior related to its search ad brokering business.

“Google has given its own comparison shopping service an illegal advantage by abusing its dominance in general Internet search,” competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager said briefing press on the 2017 antitrust decision. “It has harmed competition and consumers.”

Of course fines alone — even those that exceed a billion dollars — won’t change anything where tech giants are concerned. But each EU antitrust decision requires Google to change its regional business practices to end the anti-competitive conduct too.

Commission authorities continue monitoring Google’s compliance in all three cases, leaving the door open for further interventions if its remedies are deemed inadequate (as rivals continue to complain). So the search giant remains on close watch in Europe, where its monopoly in search puts special conditions on it not to break EU competition rules in any other markets it operates in or enters.

There are wider signs, too, that increasing antitrust scrutiny of big tech — including the idea of breaking platforms up that’s suddenly inflated into a mainstream political talking point in the U.S. — is lifting a little of the crushing weight off of Google competitors.

One example: Google quietly added privacy-focused search rival DuckDuckGo to the list of default search engines offered in its Chrome browser in around 60 markets earlier this year.

DDG is a veteran pro-privacy search engine Google rival that’s been growing usage steadily for years. Not that you’d have guessed that from looking at Chrome’s selective lists prior to the aforementioned silent update: From zero markets to ~60 overnight does look rather  .

.

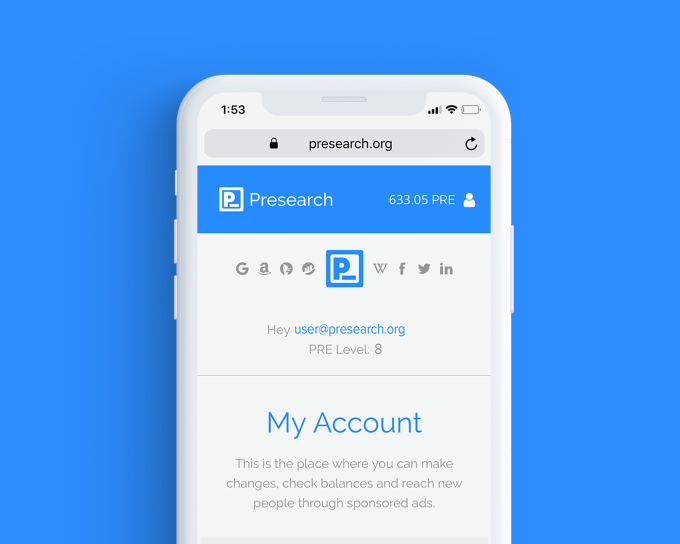

Rising antitrust risk could help unlatch more previously battened down platform hatches in a way that’s helpful to even smaller Google rivals. Search startups like Presearch . (On the size front, it’s just passed a million registered users — and says monthly active users for its beta are ~250k. Early adopters skew power user + crypto geek.)

Google’s dominance in search remains a given for now but a fresh wind is rattling tech giants thanks to a shift in tone around technology and antitrust, fuelled by societal concern about wider platform power and impacts, that’s aligned with fresh academic thinking.

And now growing, cross-spectrum political appetite to regulate the Internet. Or, to put it another way, the tech backlash smells like a vote winner.

That may seem counterintuitive when platforms have built massive consumer businesses by heavily marketing ‘free’ consumer-friendly services. But their shiny freebies have sprouted a hydra of ugly heads in recent years — whether it’s Facebook-fuelled, democracy-denting disinformation; YouTube-accelerated hate speech and extremism; or Twitter’s penchant for creating safe spaces for nazis to make friends and influence people.

Add to that: Omnipresent creepy ads that stalk people around the Internet. And a fast-flowing river of data breach scandals that have kept a steady spotlight on how the industry systematically plays fast and loose with people’s data.

European privacy regulations have further helped decloak adtech via an updated privacy legal framework that highlights how very many faceless companies are lurking in the background of the Internet, making money by selling intelligence they’ve gleaned by spying on what web users are browsing.

And that’s just the consumer side. For small businesses and startups trying to compete with platform goliaths engineered and optimized to throw their bulk around, deploying massive networks and resources to tractor-beam and data mine anything — from product development; to usage and app trends; to their next startup acquisition — the feeling can be one of complete impotence. And, well, burning injustice.

“That was actually the real genesis moment behind [Presearch] — the realization of just how big Google is,” Pape tells TechCrunch, recounting the history of the ShopCity FTC complaint. “In 2011 we woke up one day and found out that 80-90% of our Google traffic had disappeared and all of these sites, some of which had been online for more than a decade and were being run in partnership with city governments and chambers of commerce, they were all basically demoted onto page eight of Google.

“Even if you typed them by name… Google had effectively, in their own backyard, shut down this local initiative.”

“We ended up participating in this [FTC] investigation and ultimately it cleared Google but we’ve been really aware of the market power that they have — and certainly what could be perceived as monopolistic practices,” he adds. “It’s a huge challenge. Anybody trying to do any sort of publishing or anything really on the web, Google is the gatekeeper.”

Now, with Presearch, Pape and co are hoping to go after Google in its techie backyard — of search.

Search, decentralized

Breaking the “Google habit” and opening up web users to a richer and more diverse field of search alternatives is the name of the game.

Presearch’s vision is a community-owned, choice-rich online playing field in the place where the Google search box normally squats; a sort of pluralist, collaborative commons that welcomes multiple search providers and rewards and surfaces community-curated search results to further diversity — encouraging Internet users to discover a democratized multiplicity of search results, not just the things big tech wants them to see.

Or as Pape puts it: “The ultimate vision is a fully decentralized search engine where the users are actually crawling the web as they surf — and where there’s kind of a framework for all of the participants within the ecosystem to be rewarded.”

This means that Presearch, which is developing a community-contributed search engine in addition to the federated search tool platform, is competing with the third party search providers it offers access to.

But from its point of view it’s ‘the more the merrier’; Call it search choices for customizable courses.

“Or as we like to think of it, like a ‘Switzerland of search’,” says Pape, adding: “We do want to make sure it’s all about the user.”

Presearch’s startup advisor roster includes names that will be familiar to the wider blockchain community: Ethereum co-founder and founder of Decentral, Anthony Di Iorio; Rich Skrenta, founder and CEO of startup search engine Blekko (acquired by IBM Watson back in 2015); and industry lawyer, Addison Cameron-Huff.

“When you’re a producer on the web you realize how much control Google does really have over user traffic. Yet there are thousands of different search resources that are out there that are subsisting underneath of Google,” continues Pape. “So we’re really trying to give them more of a platform that a lot of these different providers — including DuckDuckGo, Qwant — could get behind to basically break that Google dependency and make it easier for them to have a direct relationship with the their audience.”

Of course they’re nowhere near challenging Google’s grip yet.

And like so many startups Presearch may never make good on the massive disruptive vision. It’s certainly got its work cut out. Being a startup in the Google-dominated search space makes the standard hostile success odds exponentially harsher.

“Presearch is a highly-ambitious project,” the startup admits in its WhitePaper. “Google is one of the best companies in the world, and #1 on the Internet. Improving on their results, experience, and integrations will be no small feat — many even say it’s impossible. However, we believe that collectively the community can creatively and elegantly fulfill its own search needs from the ground up and create an amazing and open search engine that is aligned with the interests of humanity, not just one company.”

For now the beta product is, by Pape’s ready admission, more of a “search utility” — offering a familiar search box where users can type their queries but atop a row of icons that allow them to quickly switch between different search engines or services.

As well as offering Google search (the default search engine for now), DuckDuckGo is in the list, as is French search engine Qwant. Social platforms like Facebook and LinkedIn are also there to cater to people-focused queries. As is stuff like Wikipedia for community-edited authority. In all Pape says the beta offers access to around 80 search services.

The basic idea for now is to let users select the most appropriate search tool for whatever bit of info they’re trying to locate. Aka that “level playing field for a whole bunch of different search resources” idea.

This does look like a power tool with niche appeal — Pape says about a quarter of active users are actively switching between different engines; so ~75% are not — but which is being juiced, and here comes the crypto, by rewarding users for searching via the federated search field with a token called PRE.

Pape says users are provided with a quarter token per presearch performed — up to a cap of eight tokens per day. The current market value of the PRE token is around $0.05. (So the hardest working Presearchers could presumably call themselves ’40cents’.)

While there are ways for users to extract PRE from the platform if they wish, converting it to another cryptocurrency via community built exchanges, Pape says the intent is to create more of “a closed loop ecosystem”. Hence he says they’re busy building a portal for users to be able to sell PRE tokens to advertisers.

“We will be promoting this closed loop ecosystem but it is an open standardized currency,” he notes. “It is tradable on various exchanges that community members have set up so there is the ability for people to convert the Presearch token to bitcoin which can then be converted to any local currency.”

“We see as well as opportunity to really build out an ecosystem of places for people to spend the token as well,” he adds. “So that they can exchange it directly for either digital goods or material goods through an online platform. So that’s also in the works.”

As things stand Pape says most early adopters are ‘hodlers’. Which is to say they’re holding onto their PRE — speculating on as yet unknown token economics. (As it so often goes in the blockchain space — until, well, it suddenly doesn’t.)

“There is, as throughout the entire cryptocurrency space, an element of speculation,” he agrees. “People do tend to let their imaginations run wild so there’s kind of this interesting confluence of that core base utility — where you basically have a token that is backed by advertising, something that you can really convert it to. And then there is this potential concept of the value of the network, and of having essentially some time of stake in the value of that network.

“So there’s going to be this interesting period over the next couple of years as the token economics change as we go from this nascent startup mode into more of a full on operating mode. Where the value will likely change.”

For advertisers the PRE token buys targeted ad impressions placed in front of Presearch users by being linked to keywords used by searchers (or “targeted, non-intrusive, keyword sponsorships” as the website explainer puts it).

This is the virtuous, privacy-respecting circle Presearch is hoping to create.

Pape makes a point of emphasizing there is “no tracking” of users’ searches. Which means there’s no profiling of Preseachers by Presearch itself — ads are being targeted contextually, per the current keyword search.

But of course if you’re clicking through to a third party like Google or Facebook that’s a whole other matter; and the standard tracking caveats apply.

Presearch’s claim not to be storing or otherwise tracking users’ searches has to be taken on trust for now. However it intends to fully open source the platform to ensure truly accountable transparency in the near future. (Pape says they’re hoping they’ll be able to do so in a year.)

In the meantime he notes that the founders make themselves available to users via a messaging group on Telegram — contrasting that accessibility with the perfect unreachability of Google’s founders to the average (or really almost any) Google user.

In the modern age of messaging apps, and with their ecosystem’s community-building imperatives, these founders are most certainly not operating in a vacuum.

Currently one PRE token buys an advertiser four ad impressions on the platform — which is one lever Presearch will be able to pull on to influence the value of the token as the ecosystem develops.

“Ultimately [impressions per token] could go to ten, a hundred,” suggests Pape. “That’s obviously going to change the token — and we’ll basically do that as we see the market forces at work and how many people are actually willing to sell their tokens.

“We’ve currently got a pretty strong demand side equation right now. It’s like three to one demand to supply. A lot of the people that are earning tokens are not choosing to redeem them; they’re choosing to keep them in a wallet and hold onto them for the future. So it’s an interesting experiment in tokenomics.”

“It’s super volatile, there’s so much sentiment that’s involved, that’s really the core driver of the value,” he adds. “There’s no real fundamentals yet. Nobody has established any correlation between anything.”

Presearch began life as an internal search tool built for use at the founders’ other company to reduce time tracking down information online. And then the crypto boom caught their eye — and they saw an possible incentive structure to encourage Google users to switch.

“We didn’t really see a go to market strategy with it — search is a very challenging industry. But then when we really started looking at the cryptocurrency opportunity and the ability to potentially denominate an advertising platform in a token that could be utilized to incentivize people to switch we started thinking that it was viable; we put it out to the community, we got really good feedback on the need and on the messaging.”

A token sale followed, between July and November 2017, to raise funds for developing the platform — the obvious route for Presearch to grow a blockchain-based, community-sustaining, closed-loop ecosystem.

“One of the keys was really the ownership structure and making sure that all the participants within the ecosystem are aligned under one unit of account — which is the token. Vs having conflicting interests where there’s an equity incentive as well that may run counter to that token,” notes Pape.

The token sale raised an initial $7M but lucky timing meant Presearch was riding the cryptocurrency rollercoaster during an upward wave which meant funds appreciated to around $21M by the end of the sale period.

The first version of the platform was also launched in November of 2017, with the token itself launching at the end of the month.

Since then Pape says several hundred advertisers have participated in testing phases of the platform. A new version of the platform is pending for launch “shortly” — with a different ad unit which will arrive with a dozen “curated sponsors” on board. “There’s more brand exposure so we really want to be selective in the early days and making sure that we’re only partnering with aligned projects,” he adds.

Almost a year and a half on from the original platform launch Presearch has just made good on the number one community ask: Browser extensions to make the platform easier to use for search.

User surveys showed the biggest reason people dropped out was ease of use, according to Pape.

The new extension is available for Chrome, Brave and Firefox browsers, and works to shave off usability friction. Previously beta users had to set Presearch as their homepage or remember to type its address into the URL bar before searching.

“There’s a really good alignment of the core community but ultimately it does come down to changing user habit and behavior and that is always challenging,” he adds. “This new browser extension enables them to use the browser URL field or the search field and basically access Presearch through the UI that they’re used to and that they’ve been demanding.

Around a quarter of sign-ups stick around and become active users, according to Pape — who dubs that “already really high”. The team is expecting the new browser extensions to fuel “significant” further growth.

“We are getting ready to push it out to the users through email — [and anticipate] that we’re going to see a significant increase in the percentage of users utilizing it. And if that assumption holds through and everything really holds out we’re going to do a much more active push to grow the user base.”

They also launched an iOS Presearch app last year which taps into the voice search trend. Users can speak to search specific services with a library of sites that can be added to the app to enable deep searching of web resources, as well as apps running locally on the device. (So, for example, you could tap and tell it to ‘presearch Google Maps for London’ or ‘Spotify for Taylor Swift’.)

Competition concerns attached to the convenience of voice search — which risks further flattening consumer choice and concentrating already highly concentrated market power given its focus on filtering options to return just one search result — is an area of interest for antitrust regulators.

Europe’s antitrust chief Vestager said in an interview earlier this year that she was trying to figure out “how to have competition when you have voice search”. So perhaps Presearch’s federated platform approach offers a glimpse of a possible solution.

Global community vs Google

Pape sums up the overall competitive positioning that Presearch is shooting for as “Google for usage, DuckDuckGo for positioning”.

“We have been focused on the cryptocurrency community but there’s a really big opportunity to help all these other content providers, internet service providers,” he argues. “There’s all this traffic that is happening and it’s currently defaulting over to Google with really no compensation to the publishers — or to the tech provider. And so we’re going to be going after those opportunities pretty aggressively to get people to basically replace Google as the default that they use if they’re linking in an article to some more information or if they are an ISP and they have an error page that shows up if somebody types in a URL wrong or types in a strange query or something. Rather than have it go to Google, have it go to Presearch.”

Trying to make crypto more accessible is another focus. So there’s a built-in wallet to store PRE tokens — meaning users don’t have to have their own wallet set up to start earning crypto. (Though of course they can move PRE into a different wallet if/when they want.)

“As far as geographies go it’s a global audience but there’s a pretty heavy contingent of users in Central and South America… Mexico, Brazil, Venezuela,” he adds, discussing where early interest has been coming from. “There’s a lot of crypto adoption that’s happening down there due to this [combination] where they’re super tech savvy, they’ve got really great infrastructure, but they are still in a developing nation. So any of these types of crypto opportunities are very significant to them.”

While Google remains the staple default search option Presearch does offer its own search engine — leaning on third party APIs for search results.

Pape says the plan is to switch from Google to this engine as the default down the line. Albeit they can’t justify the switch yet.

“We want to provide users with the best search results to start,” he concedes, before adding: “Up until just recently Google’s results were certainly superior; now we think we’ve got something that is actually quite competitive.”

He couches the Presearch engine as “very similar to DuckDuckGo” but with a couple of “unique features” — including an infinite scroll view, rather than having search results paginated. (“As you’re scrolling it will automatically refresh the results.”)

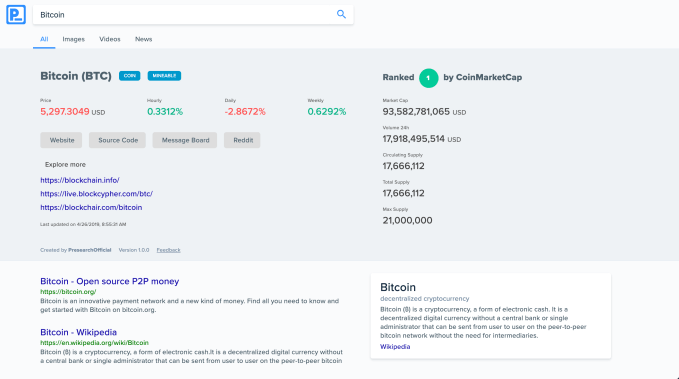

“But the biggest thing really is that we have these open source community packages so anybody can submit to us a package that would get triggered by certain keywords and basically show up with results at the top of the search.”

An example of one of these community packages can be seen by conducting a Presearch for “bitcoin” — which returns the below block of curated info related to the cryptocurrency above the rest of the search results:

Another example is currency conversions. When a currency conversion is typed into Presearch as a search query in the correct format (using relevant acronyms like USD and CAD) the query will surface a currency converter built by community members.

“It’s basically enabling anybody who knows HTML or Javascript to participate within the search ecosystem and add value to Presearch,” adds Pape.

The ultimate goal with the Presearch engine is to offer fully community-powered search where users not only create content packages and build out wider utility that can be served for particular keywords/searches but also curate these packages too.

The aim is also to have the community manage the entire process — such as by voting on what package should be the default where there are conflicting packages; and/or voting to approve package updates — much like Wikipedia editors work together on editing the online encyclopedia’s entries.

Pape notes that users would still be able to customize their own search results, such as by browsing the full suite of approved packages and selecting those that best meet their needs.

“The whole concept of the search engine is really more about user choice and giving them the ability to actively personalize their search results, and choose which contributors within the ecosystem they want to support,” he adds.

Of course Presearch is a very long way off that grand vision of wholly-community-powered search. So for now community packages are being curated by its core dev team.

Nor is it the first startup to dream big of community-powered and owned search. Not by a long, long chalk. It’s an idea that’s been kicked around the block many times before, even as Google’s dominating grip on search has cemented itself into place.

The level of crowdsourced effort required to generate differentiating value in the Google-dominated search space has proved a stumbling block for similarly minded startups wanting to compete head to head with Mountain View. And, clearly, Presearch will need a much larger user base if it’s to build and sustain enough community contributions to make its engine a compellingly useful product vs the usual search giant suspects.

But, as with Wikipedia, the idea is to keep building utility and momentum in growing increments. With — in its case — crypto rewards, backed by $21M in initial token sales, as the carrot to encourage community participation and contribution. So the founder logic sums to: ‘If we build it and pay people they’ll come’.

It’s worth noting that despite the community-focused mission Presearch’s current corporate structure is a Canadian corporation.

It does have a plan to transition to a foundation in future — with Pape envisaging distributing ~90%+ of the revenue that flows through the ecosystem to the various constituents and participants (searchers; node operators; curators; subject matter experts contributing to information indexes etc, etc), and retaining around 10% to fund operating the platform entity itself.

This is a structure familiar to many blockchain projects. Though Presearch is perhaps a bit unusual by being initially incorporated as a business.

“A lot of the crypto projects have done this foundation route [right off the bat] but really it’s more about taxes and it’s more about jurisdictional arbitrage and trying to minimize the potential regulatory risk,” Pape suggests. “For us, because of the way that we launched it, and our legal advisor [Cameron-Huff] — the founding lawyer for Ethereum — he gave us some really good guidance right out of the gate. And we’ve treated it as a business.

“We think we’ve got a really strong legal position and so we really didn’t need to do the offshore stuff at first. We figured we would get the usage and build up the core token economics. And then switch to an actual truly community-governed foundation, rather than a foundation in name which is governed by all the insiders — which is really what most of the crypto projects currently have done.”

For now Pape remains the sole shareholder of Presearch. Transitioning that sole ownership into the future foundation structure is likely a year out by his reckoning.

“One of the key concepts behind the project is ultimately providing an open source, transparent resource that is treated like more of a utility, that the community can provide input on and manage,” he adds. “So we’re looking at all the different government options.

“There’s a lot of technology being developed within the blockchain space right now. And some best practices that are starting to emerge. So we figured that we would give it a little while for that technology and those practices to mature and then we would be able to do that transition.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Some reassuring data for those worried unicorns are wrecking the Bay Area

Contributor

The San Francisco Bay Area is a global powerhouse at launching startups that go on to dominate their industries. For locals, this has long been a blessing and a curse.

On the bright side, the tech startup machine produces well-paid tech jobs and dollars flowing into local economies. On the flip side, it also exacerbates housing scarcity and sky-high living costs.

These issues were top-of-mind long before the unicorn boom: After all, tech giants from Intel to Google to Facebook have been scaling up in Northern California for over four decades. Lately however, the question of how many tech giants the region can sustainably support is getting fresh attention, as Pinterest, Uber and other super-valuable local companies embark on the IPO path.

The worries of techie oversaturation led us at Crunchbase News to take a look at the question: To what extent do tech companies launched and based in the Bay Area continue to grow here? And what portion of employees work elsewhere?

For those agonizing about the inflationary impact of the local unicorn boom, the data offers a bit of reassurance. While companies founded in the Bay Area rarely move their headquarters, their workforces tend to become much more geographically dispersed as they grow.

Headquarters ≠ headcount

Just because a company is based in Northern California doesn’t mean most workers are there also. Headquarters, our survey shows, does not always translate into headcount.

“Headquarters location can often be the wrong benchmark to use to identify where employees are located,” said Steve Cadigan, founder of Cadigan Talent Ventures, a Silicon Valley-based talent consultancy. That’s particularly the case for large tech companies.

Among the largest technology employers in Northern California, Crunchbase News found most have fewer than 25 percent of their full-time employees working in the city where they’re headquartered. We lay out the details for 10 of the most valuable regional tech companies in the chart below.

With the exception of Intel, all of these companies have a double-digit percentage of employees at headquarters, so it’s not as if they’re leaving town. However, if you’re a new hire at Silicon Valley’s most valuable companies, it appears chances are greater that you’ll be based outside of headquarters.

Tesla, meanwhile, is somewhat of a unique case. The company is based in Palo Alto, but doesn’t crack the city’s list of top 10 employers. In nearby Fremont, Calif., however, Tesla is the largest city employer, with roughly 10,000 reportedly working at its auto plant there.(Tesla has about 49,000 employees globally.)

Unicorns flock to San Fran, workers less so

High-valuation private and recently public tech companies can also be pretty dispersed.

Although they tend to have a larger percentage of employees at headquarters than more-established technology giants, the unicorn crowd does like to spread its wings.

Take Uber, the poster child for this trend. Although based in San Francisco, the ride-hailing giant has fewer than one-fourth of its employees there. Out of a global workforce of around 22,300, only about 5,000 are SF-based.

It’s unclear if that kind of breakdown is typical. We had trouble assembling similar geographic employee counts at other Bay Area unicorns, mainly because cities break out numbers only for their 10 largest employers. The lion’s share of regional unicorns are San Francisco-based, and of them only Uber made the Top 10.

That said, there is another, rougher methodology for assessing who works at headquarters: job postings. At a number of the most valuable Bay Area-based unicorns — including Airbnb, Juul, Lime, Instacart, Stripe and the now-public Lyft — a high number of open positions are far from the home office. And as we wrote last year, private companies have been actively seeking out cities to set up secondary hubs.

Even for earlier-stage startups, it’s not uncommon to set up headquarters in the San Francisco area for access to financing and networking, while doing the bulk of hiring in another location, Cadigan said. The evolution of collaborative work tools has also enabled more companies to add staff working remotely or in secondary offices.

Plus, of course, unicorn startups tend to be national or global in focus, and that necessitates hiring where their customers are located.

Take our jobs, please

As we wrap up, it’s worth bringing up how unusual it once was for denizens of a metro area to oppose a big influx of high-skill jobs. In the past couple of years, however, these attitudes have become more common. Witness Queens residents’ mixed reactions to Amazon’s HQ2 plans. And in San Francisco, a potential surge of newly minted IPO millionaires is causing some consternation among locals, along with jubilation among the realtor crowd.

Just as college towns retain room for new students by graduating older ones, however, it seems reasonable that sustaining Northern California’s strength as a startup hub requires locating jobs out-of-area as companies scale. That could be good news for other cities, including Austin, Phoenix, Nashville, Portland and others, which have emerged as popular secondary locations for fast-growing unicorns.

That said, we’re not predicting near-term contraction in Bay Area tech employment, particularly of the startup variety. The region’s massive entrepreneurial and venture ecosystem keeps on producing valuable newcomers well-capitalized to keep hiring.

Methodology

We looked only at employment at company headquarters (except for Apple) . Companies on the list may have additional employees based in other Northern California cities. For Apple, we included all Silicon Valley employees, per estimates by the Silicon Valley Business Journal.

Numbers are rounded to the nearest hundred for the largest employers. Most of the data is for full-time employees only. Large tech employers hire predominantly full-time for staff positions, so part-time, whether included or not, is expected to reflect only a very small percentage of employment.

Cities list their 10 largest employers in annual reports. We used either the annual reports themselves or data excerpted in Wikipedia, using calendar year 2017 or 2018.

Powered by WPeMatico