BenevolentAI, which uses AI to develop drugs and energy solutions, nabs $115M at $2B valuation

In the ongoing race to build the best and smartest applications that tap into the advances of artificial intelligence, a startup out of London has raised a large round of funding to double down on solving persistent problems in areas like healthcare and energy. BenevolventAI announced today that it has raised $115 million to continue developing its core “AI brain” as well as different arms of the company that are using it specifically to break new ground in drug development and more.

This venture round values the company at $2.1 billion post-money, its founder and executive chairman Ken Mulvaney confirmed to TechCrunch. Investors in this round include previous backer Woodford Investment Management, and while Mulvaney said the company was not disclosing the names of any other investors, he added it was a mix of family offices and some strategic backers, with a majority coming from the U.S., but would not specify any more. Notably, BenevolentAI does not have any backing from more traditional VCs, which more generally have been doubling down on investments in AI startups. Founded in 2013, the company has now raised more than $200 million to date.

The core of BenevolentAI’s business is focused around what Mulvaney describes as a “brain” built by a team of scientists — some of whom are disclosed, and some of whom are not, for competitive reasons; Mulvaney said: There are 155 people working at the startup in all, with 300 projected by the end of this year. The brain has been created to ingest and compute billions of data points in specific areas such as health and material science, to help scientists better determine combinations that might finally solve persistently difficult problems in fields like medicine.

The crux of the issue in a field like drug development, for example, is that even as scientists identify the many permutations and strains of, say, a particular kind of cancer, each of these strains can mutate, and that is before you consider that each mutation might behave completely differently depending on which person develops the mutation.

This is precisely the kind of issue that AI, which is massive computational power and “learning” from previous computations, can help address. (And BenevolventAI is not the only one taking this approach. Specifically in cancer, others include Grail and Paige.AI.)

But even with the speed that AI brings to the table, it’s a very long, long game for BenevolentAI. The division of BenevolentAI that is focused on drugs, called Benevolent Bio, currently has two drugs in more advanced stages of development, Mulvaney said, although neither of those happen to be in the area of cancer. A Parkinson’s drug is currently in Phase 2B clinical trials, after years of work.

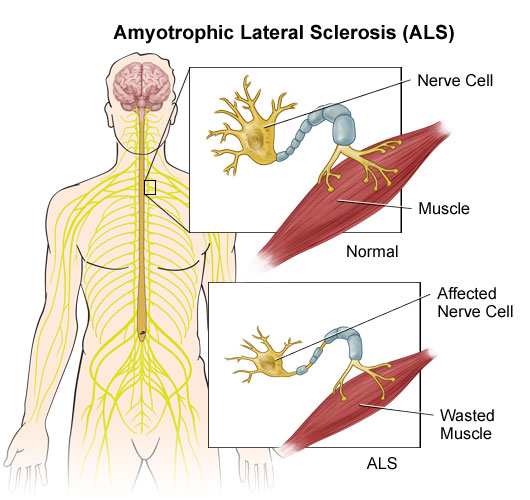

And an ALS medication currently in development — which Mulvaney says will aim to significantly extend the prospects for those who have been diagnosed with ALS — is about five years away from trials. It’s worth the effort to try, though: The best ALS medications on the market today at best only add about three months to a patient’s life expectancy.

And an ALS medication currently in development — which Mulvaney says will aim to significantly extend the prospects for those who have been diagnosed with ALS — is about five years away from trials. It’s worth the effort to try, though: The best ALS medications on the market today at best only add about three months to a patient’s life expectancy.

Some of the long period of development is because with drugs, there is a large regulatory framework a company must go through. “But we benefit from that,” Mulvaney said, “because it means you can actually then offer something in the market.” (Blood tests à la Theranos are very different in terms of regulatory requirements, he said.)

In part because of that long cycle, and also because BenevolentAI has spotted an adjacent opportunity, the company has more recently also been extending applications from its “brain” to other adjacent areas that also tap into chemistry and biology, such as material science.

One area Mulvaney said is of particular interest is to see if Benevolent can create materials that can both withstand extreme heat — to allow engines to work at higher rates without risks — as well as chemicals that could essentially create the next generation of efficient batteries that could provide more power in smaller formats for longer periods.

“There has been little development beyond a lithium-ion battery,” he noted, which may be fine for the Teslas of the world today. “But there is not enough lithium on this planet for us all to go electric, and there is not nearly enough energy density there unless you have thousands of batteries working together. We need other technology to provide more energy donation. That tech doesn’t exist yet because chemically it’s very difficult to do that.” And that spells opportunity for BenevolentAI.

Other areas where the startup hopes to move into over the coming months and years include agriculture, veterinary science, and other categories that sit alongside those BenevolentAI is already tapping.

Powered by WPeMatico