Asia

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

This week, I’ve tried to do something new at TechCrunch with this experimental column — getting obsessed about a topic broadly in tech and writing a continuous stream of thoughts and analysis about it.

With my research consultant and contributor Arman Tabatabai, we’ve covered two topics: Form Ds, the filing that startups usually submit to the SEC after a venture round closes (although increasingly do not), and SoftBank, which faces all kinds of strategic pressure due to its debt binging. If you missed the other episodes, here are links to the editions from Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday.

We are experimenting with new content forms at TechCrunch. This is a rough draft of something new — provide your feedback directly to the authors: Danny at danny@techcrunch.com or Arman at Arman.Tabatabai@techcrunch.com if you like or hate something here.

Today, one final round of thoughts on SoftBank and Rakuten (heavily written by Arman) and a lengthy list of articles for your weekend reading.

BEHROUZ MEHRI/AFP/Getty Images

Understanding SoftBank’s competitive strategy requires a bit of a deep dive into Japanese e-commence giant Rakuten.

Rakuten has been struggling to compete with Amazon and others like SoftBank’s Yahoo! Japan. So at the end of 2017, Rakuten announced it would be entering the telco space, hoping that operating its own network could generate user growth through better incentives around mobile shopping, streaming and payments.

Today, Japan’s telco space is a relatively cozy oligopoly dominated by NTT DoCoMo, au-KDDI and SoftBank. A major reason why Rakuten feels it can succeed where others have failed to break in is because it has the government on its side.

Rakuten’s plan to offer prices at least 30 percent lower than incumbent rates has led to favorable treatment from Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government, which has been looking for ways to stimulate market competition to force lower the country’s high phone prices.

Though a new entrant hasn’t been approved to enter the telco market since eAccess in 2007, Rakuten has already gotten the thumbs-up to start operations in 2019. The government also instituted regulations that would make the new kid in town more competitive, such as banning telcos from limiting device portability.

Rakuten’s partnerships with key utilities and infrastructure players will also allow it to build out its network quickly, including one with Japan’s second largest mobile service provider, KDDI.

Just last week, Rakuten and KDDI announced an agreement where Rakuten will help KDDI utilize its payment and logistics infrastructure as KDDI turns its head toward e-commerce and payments, while KDDI will give Rakuten access to its network and nationwide roaming services, allowing Rakuten to provide nationwide service as its builds out its own infrastructure.

The agreement with KDDI is especially scary for SoftBank, the country’s third biggest telco and one of Rakuten’s e-commerce competitors, and whose customers seem most vulnerable to churn. The partnership also makes it seem even more likely that SoftBank’s competitors are looking to push it out of the market or turn into a dud its upcoming mobile segments IPO.

While Rakuten’s head-first dive into the market won’t ease investors into an IPO, it’s important we note that Rakuten is targeting a much smaller market share than the incumbents, targeting 10 million subscribers by 2028, a number lower than the company’s original 15 million subs goal and significantly lower than the 76 million, 52 million and 40 million subscribers NTT, KDDI and SoftBank (respectively) hold currently. And even with its agreements, Rakuten faces a serious and expensive uphill battle in building out its network infrastructure quickly enough to compete.

Ultimately, Rakuten’s telco initiative is a splash, but one that seems like it will merely make its competitors wet and not drown them. For SoftBank, it is an annoying distraction on its telco IPO roadshow, but a distraction that is easily explained to potential investors.

Rajeev Misra. Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Changing gears from Rakuten, emails from readers this week asked us to look deeper into SoftBank’s performance over the last two decades. As we did so, it became clear that SoftBank has had a long history of price competitions and new entrants across its businesses, and it has proven its ability to operate and consistently grow earnings.

Since 2000, SoftBank has grown earnings at a ~30 percent CAGR and experienced revenue growth in all but one year. When eAccess did enter the telco market and picked up four million subscribers, SoftBank bought it and integrated it into its own system.

As we discussed earlier this week, despite having always held on to a clunky amount of debt, SoftBank has managed to deliver consistent growth by making sure its revenue and operating growth outpaced the upticks in its debt and interest expense.

A great example of this came after SoftBank’s acquisition of Vodafone in 2006, when it saw a huge spike in its interest expense, but also in its operating income.

Over the following five years, SoftBank managed to reduce its interest expense at an annual rate of 12 percent while growing its operating income at 16 percent. And regardless of its debt balances, SoftBank has always seemingly been able to secure funding one way or another, as shown by its ability to raise $90+ billion for the Vision Fund in less than a year from when plans for the fund were first reported.

The Vision Fund itself started as a way for SoftBank to continue to invest while its balance sheet was tight due to nearly back-to-back massive acquisitions of Sprint and Arm. Just look at how Rajeev Misra, who oversees the Vision Fund, discussed its creation in an interview with The Economic Times:

We had just bought ARM in June for $32 billion and Masa felt we are on the cusp of a technology revolution over the next 5-10 years with machine learning, AI, robotics and the impact of that in disrupting every industry – from healthcare to financial services to manufacturing.

We felt the world was going through a new industrial revolution. We were constrained financially given that we just did a $32-billion acquisition.

SoftBank, historically over the last 20 years, has invested from its own balance sheet. So, we had two options.

Either monetise some of the gains we made in Alibaba which we decided has a lot more upside… Alibaba has more than doubled in the last 12 months. So we decided to keep it which turned out to be good decision. The second option was to go out and raise money and co-invest with others. We prepared a presentation, went out, and by god’s grace we raised the fund.

Even before the Vision Fund, SoftBank has always had a strategy to make big bets in industries of the future. And while many have failed, the several that have paid off, like its $20 million investment in Alibaba, had massive cash outs that have driven consistent earnings growth for decades. SoftBank seems to be banking its future on the same strategy and, frankly, it’s unclear how much they even care about how competitive their telco is, as shown by this exchange in the same interview with Misra:

Question: What about sectors like telecom?

Misra: Let the dust settle.

Our obsession with SoftBank this week is probably going to subside, and we are in the market for our next deep dive topic in tech and finance. Have ideas? Drop us a line at danny@techcrunch.com and arman.tabatabai@techcrunch.com

Photo by Darren Johnson / EyeEm via Getty Images

The CIA’s communications suffered a catastrophic compromise. It started in Iran. This is a great follow-up from Yahoo News’ Zach Dorfman and Jenna McLaughlin on one of the most important espionage stories this past decade. The CIA, using an internet-based communications system to connect with spies and sources in the field, failed to keep the security of the system intact, leading to the dismantling of its Iranian, Chinese and potentially other espionage rings. This article advances the story as we know it from the New York Times’ original piece, and Foreign Policy’s excellent follow up also written by Zach Dorfman. Definitely worth a read from a security/technical audience. (3,200 words)

The $6 Trillion Barrier Holding Electric Cars Back. Don’t read — the answer is infrastructure. (1,000 words, but should be one)

The Rodney Brooks Rules for Predicting a Technology’s Commercial Success. A a good reminder that some technologies are much closer to reality than others, and that the key difference between them is our collective experience handling the technology. Rodney Brooks is the right person to cover this subject, although one can’t help but feel that every example is Musk-inspired. (2,800 words)

Uber’s economics team is its secret weapon by Alison Griswold & Soon there may be more economists at tech companies than in policy schools by Roberta Holland, both in Quartz . Griswold does a great job giving an overview of how Uber is using economists not just to improve its product for end users, but also to shape the discussion of public policy around the company. Clearly, Uber is not alone; as Holland notes in her piece, academic economists are very popular in Silicon Valley right now, with salaries that can match the top machine learning experts. (2,750 words and 1,200 words, respectively)

The future’s so bright, I gotta wear blinders. A short piece by Nicholas Carr fighting back against the notion that computing is still “at the beginning.” Many of our devices and pieces of software are already decades old — if they haven’t had an effect on human behavior or productivity, when are they going to? A useful antidote to some ideas we hear from the Valley every single day. (900 words)

The future of photography is code. Yes, yes, I am very late to this — blame Pocket disease. TechCrunch’s own Devin Coldewey writes a candid essay on the transition from improving photography through hardware like lenses to improving photos through computation. The future is looking very bright for beautiful photos, indeed. (2,400 words)

Freedom on the Net 2018 | Freedom House. And if you are looking for some depressing news, Freedom House’s report (which I am also a bit late to) is dreary. China is now increasingly the source of authoritarian internet control technology, and countries across the world are backtracking on internet freedom (including the U.S.). Sobering, but with so much riding on the openness of the internet, we all need to pay attention and build the kind of future for this technology that we want. (32 page PDF with exec summary)

What we are reading (or at least, trying to read)

Powered by WPeMatico

The holiday season is here again, touting all sorts of kids’ toys that pledge to pack ‘STEM smarts’ in the box, not just the usual battery-based fun.

Educational playthings are nothing new, of course. But, in recent years, long time toymakers and a flurry of new market entrants have piggybacked on the popularity of smartphones and apps, building connected toys for even very young kids that seek to tap into a wider ‘learn to code’ movement which itself feeds off worries about the future employability of those lacking techie skills.

Whether the lofty educational claims being made for some of these STEM gizmos stands the test of time remains to be seen. Much of this sums to clever branding. Though there’s no doubt a lot of care and attention has gone into building this category out, you’ll also find equally eye-catching price-tags.

Whatever STEM toy you buy there’s a high chance it won’t survive the fickle attention spans of kids at rest and play. (Even as your children’s appetite to be schooled while having fun might dash your ‘engineer in training’ expectations.) Tearing impressionable eyeballs away from YouTube or mobile games might be your main parental challenge — and whether kids really need to start ‘learning to code’ aged just 4 or 5 seems questionable.

Buyers with high ‘outcome’ hopes for STEM toys should certainly go in with their eyes, rather than their wallets, wide open. The ‘STEM premium’ can be steep indeed, even as the capabilities and educational potential of the playthings themselves varies considerably.

At the cheaper end of the price spectrum, a ‘developmental toy’ might not really be so very different from a more basic or traditional building block type toy used in concert with a kid’s own imagination, for example.

While, at the premium end, there are a few devices in the market that are essentially fully fledged computers — but with a child-friendly layer applied to hand-hold and gamify STEM learning. An alternative investment in your child’s future might be to commit to advancing their learning opportunities yourself, using whatever computing devices you already have at home. (There are plenty of standalone apps offering guided coding lessons, for example. And tons and tons of open source resources.)

For a little DIY STEM learning inspiration read this wonderful childhood memoir by TechCrunch’s very own John Biggs — a self-confessed STEM toy sceptic.

It’s also worth noting that some startups in this still youthful category have already pivoted more toward selling wares direct to schools — aiming to plug learning gadgets into formal curricula, rather than risking the toys falling out of favor at home. Which does lend weight to the idea that standalone ‘play to learn’ toys don’t necessarily live up to the hype. And are getting tossed under the sofa after a few days’ use.

We certainly don’t suggest there are any shortcuts to turn kids into coders in the gift ideas presented here. It’s through proper guidance — plus the power of their imagination — that the vast majority of children learn. And of course kids are individuals, with their own ideas about what they want to do and become.

The increasingly commercialized rush towards STEM toys, with hundreds of millions of investor dollars being poured into the category, might also be a cause for parental caution. There’s a risk of barriers being thrown up to more freeform learning — if companies start pushing harder to hold onto kids’ attention in a more and more competitive market. Barriers that could end up dampening creative thinking.

At the same time (adult) consumers are becoming concerned about how much time they spend online and on screens. So pushing kids to get plugged in from a very early age might not feel like the right thing to do. Your parental priorities might be more focused on making sure they develop into well rounded human beings — by playing with other kids and/or non-digital toys that help them get to know and understand the world around them, and encourage using more of their own imagination.

But for those fixed on buying into the STEM toy craze this holiday season, we’ve compiled a list of some of the main players, presented in alphabetical order, rounding up a selection of what they’re offering for 2018, hitting a variety of price-points, product types and age ranges, to present a market overview — and with the hope that a well chosen gift might at least spark a few bright ideas…

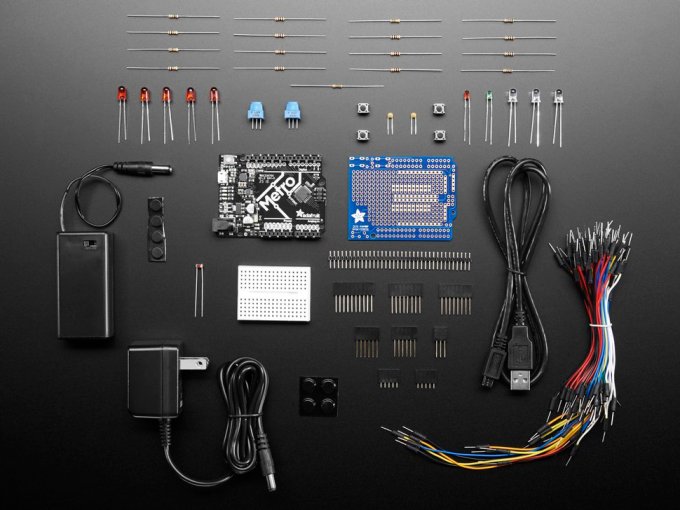

Product: Metro 328 Starter Pack

Price: $45

Description: Not a typical STEM toy but a starter kit from maker-focused and electronics hobbyist brand Adafruit. The kit is intended to get the user learning about electronics and Arduino microcontrollers to set them on a path to being a maker. Adafruit says the kit is designed for “everyone, even people with little or no electronics and programming experience”. Though parental supervision is a must unless you’re buying for a teenager or mature older child. Computer access is also required for programming the Arduino.

Be sure to check out Adafruit’s Young Engineers Category for a wider range of hardware hacking gift ideas too, from $10 for a Bare Conductive Paint Pen, to $25 for the Drawdio fun pack, to $35 for this Konstruktor DIY Film Camera Kit or $75 for the Snap Circuits Green kit — where budding makers can learn about renewable energy sources by building a range of solar and kinetic energy powered projects. Adafruit also sells a selection of STEM focused children’s books too, such as Python for Kids ($35)

Age: Teenagers, or younger children with parental supervision

[inline-ads]

Product: Cozmo

Price: $180

Description: The animation loving Anki team added a learn-to-code layer to their cute, desktop-mapping bot last year — called Cozmo Code Lab, which was delivered via free update — so the cartoonesque, programmable truck is not new on the scene for 2018 but has been gaining fresh powers over the years.

This year the company has turned its attention to adults, launching a new but almost identical-looking assistant-style bot, called Vector, that’s not really aimed at kids. That more pricey ($250) robot is slated to be getting access to its code lab in future, so it should have some DIY programming potential too.

Age: 8+

Product: Kamigami Jurassic World Robot

Price: ~$60

Description: Hobbyist robotics startup Dash Robotics has been collaborating with toymaker Mattel on the Kamigami line of biologically inspired robots for over a year now. The USB-charged bots arrive at kids’ homes in build-it-yourself form before coming to programmable, biomimetic life via the use of a simple, icon-based coding interface in the companion app.

The latest addition to the range is dinosaur bot series Jurassic World, currently comprised of a pair of pretty similar looking raptor dinosaurs, each with light up eyes and appropriate sound effects. Using the app kids can complete challenges to unlock new abilities and sounds. And if you have more than one dinosaur in the same house they can react to each other to make things even more lively.

Age: 8+

Product: Harry Potter Coding Kit

Price: $100

Description: British learn-to-code startup Kano has expanded its line this year with a co-branded, build-it-yourself wand linked to the fictional Harry Potter wizard series. The motion-sensitive e-product features a gyroscope, accelerometer, magnetometer and Bluetooth wireless so kids can use it to interact with coding content on-screen. The company offers 70-plus challenges for children to play wizard with, using wand gestures to manipulate digital content. Like many STEM toys it requires a tablet or desktop computer to work its digital magic (iOS and Android tablets are supported, as well as desktop PCs including Kano’s Computer Kit Touch, below)

Age: 6+

Product: Computer Kit Touch

Price: $280

Description: The latest version of Kano’s build-it-yourself Pi-powered kids’ computer. This year’s computer kit includes the familiar bright orange physical keyboard but now paired with a touchscreen. Kano reckons touch is a natural aid to the drag-and-drop, block-based learn-to-code systems it’s putting under kids’ fingertips here. Although its KanoOS Pi skin does support text-based coding too, and can run a wide range of other apps and programs — making this STEM device a fully fledged computer in its own right

Age: 6-13

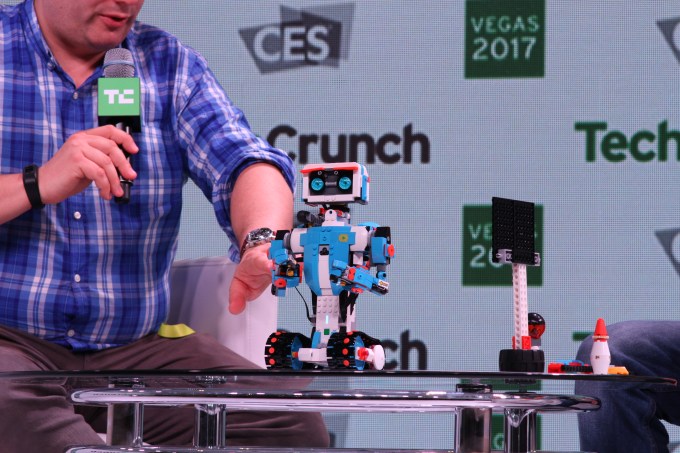

Product: Boost Creative Toolbox

Price: $160

Description: Boost is Lego’s relatively recent foray into offering a simpler robotics and programming system aimed at younger kids vs its more sophisticated and expensive veteran Mindstorms creator platform (for 10+ year olds). The Boost Creative Toolbox is an entry point to Lego + robotics, letting kids build a range of different brick-based bots — all of which can be controlled and programmed via the companion app which offers an icon-based coding system.

Boost components can also be combined with other Lego kits to bring other not-electronic kits to life — such as its Stormbringer Ninjago Dragon kit (sold separately for $40). Ninjago + Boost means = a dragon that can walk and turn its head as if it’s about to breathe fire

Age: 7-12

Product: Avengers Hero Inventor Kit

Price: $150

Description: This Disney co-branded wearable in kit form from the hardware hackers over at littleBits lets superhero-inspired kids snap together all sorts of electronic and plastic bits to make their own gauntlet from the Avengers movie franchise. The gizmo features an LED matrix panel, based on Tony Stark’s palm Repulsor Beam, they can control via companion app. There are 18 in-app activities for them to explore, assuming kids don’t just use amuse themselves acting out their Marvel superhero fantasies

Age: 8+

It’s worth noting that littleBits has lots more to offer — so if bringing yet more Disney-branded merch into your home really isn’t your thing, check out its wide range of DIY electronics kits, which cater to various price points, such as this Crawly Creature Kit ($40) or an Electronic Music Inventor Kit ($100), and much more… No major movie franchises necessary

Product: Codey Rocky

Price: $100

Description: Shenzhen-based STEM kit maker Makeblock crowdfunded this emotive, programmable bot geared towards younger kids on Kickstarter. There’s no assembly required, though the bot itself can transform into a wearable or handheld device for game playing, as Codey (the head) detaches from Rocky (the wheeled body).

Despite the young target age, the toy is packed with sophisticated tech — making use of deep learning algorithms, for example. While the company’s visual programming system, mBlock, also supports Python text coding, and allows kids to code bot movements and visual effects on the display, tapping into the 10 programmable modules on this sensor-heavy bot. Makeblock says kids can program Codey to create dot matrix animations, design games and even build AI and IoT applications, thanks to baked in support for voice, image and even face recognition… The bot has also been designed to be compatible with Lego bricks so kids can design and build physical add-ons too

Age: 6+

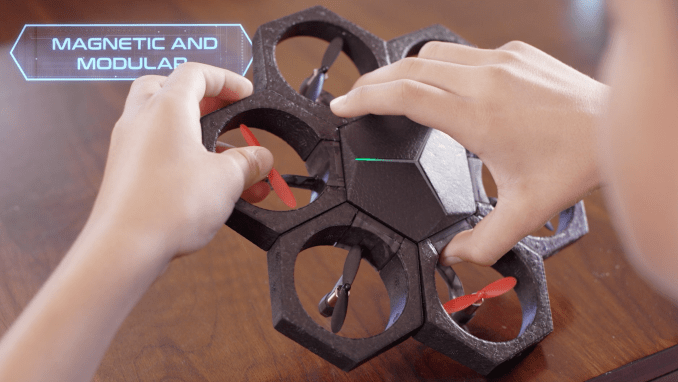

Product: Airblock

Price: $100

Description: Another programmable gizmo from Makeblock’s range. Airblock is a modular and programmable drone/hovercraft so this is a STEM device that can fly. Magnetic connectors are used for easy assembly of the soft foam pieces. Several different assembly configurations are possible. The companion app’s block-based coding interface is used for programming and controlling your Airblock creations

Age: 8+

Product: Evo

Price: $100

Description: This programmable robot has a twist as it can be controlled without a child always having to be stuck to a screen. The Evo’s sensing system can detect and respond to marks made by marker pens and stickers in the accompanying Experience Pack — so this is coding via paper plus visual cues.

There is also a digital, block-based coding interface for controlling Evo, called OzoBlockly (based on Google’s Blockly system). This has a five-level coding system to support a range of ages, from pre-readers (using just icon-based blocks), up to a ‘Master mode’ which Ozobot says includes extensive low-level control and advanced programming features

Age: 9+

Product: Modular Laptop

Price: $320 (with a Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+), $285 without

Description: This snazzy 14-inch modular laptop, powered by Raspberry Pi, has a special focus on teaching coding and electronics. Slide the laptop’s keyboard forward and it reveals a built in rail for hardware hacking. Guided projects designed for kids include building a music maker and a smart robot. The laptop runs pi-top’s learn-to-code oriented OS — which supports block-based coding programs like Scratch and kid-friendly wares like Minecraft Pi edition, as well as its homebrew CEEDUniverse: A Civilization style game that bakes in visual programming puzzles to teach basic coding concepts. The pi-top also comes with a full software suite of more standard computing apps (including apps from Google and Microsoft). So this is no simple toy. Not a new model for this year — but still a compelling STEM machine

Age: 8+

Product: Starter Kit

Price: $200

Description: Programmable robotics blocks for even very young inventors. The blocks snap together and are color-coded based on function so as to minimize instruction for the target age group. Kids can program their creations to do stuff like drive, play music, detect obstacles and more via a drag-and-drop coding interface in the companion Robo Code app. Another app — Robo Live — lets them control what they’ve built in real time. The physical blocks can also support Lego-based add-ons for more imaginative designs

Age: 5+

Product: Root

Price: $200

Description: A robot that can sense and draw, thanks to a variety of on board sensors, battery-powered kinetic energy and its central feature: A built-in pen holder. Root uses spirographs as the medium for teaching STEM as kids get to code what the bot draws. They can also create musical compositions with a scan and play mode that turns Root into a music maker. The companion app offers three levels of coding interfaces to support different learning abilities and ages. At the top end it supports programming in Swift (with Python and JavaScript slated as coming soon). An optional subscription service offers access to additional learning materials and projects to expand Root’s educational value

Age: 4+

Product: Bolt

Price: $150

Description: The app-enabled robot ball maker’s latest STEM gizmo. It’s still a transparent sphere but now has an 8×8 LED matrix lodged inside to expand the programmable elements. This colorful matrix can be programmed to display words, show data in real-time and offer game design opportunities. Bolt also includes an ambient light sensor, and speed and direction sensors, giving it an additional power up over earlier models. The Sphero Edu companion app supports drawing, Scratch-style block-based and JavaScript text programming options to suit different ages

Age: 8+

Product: Range of coding, electronics and craft kits

Price: From ~$30 up to $150

Description: A delightful range of electronic toys and coding kits, hitting various age and price-points, and often making use of traditional craft materials (which of course kids love). Examples include a solar powered moisture sensor kit ($40) to alert when a pot plant needs water; electronic dough ($35); a micro:bot add-on kit ($35) that makes use of the BBC micro:bit device (sold separately); and the creative coder kit ($70), which pairs block-based coding with a wearable that lets kids see their code in action (and reacting to their actions)

Age: 4+, 8+, 11+ depending on kit

Product: JIMU Robot BuilderBots Series: Overdrive Kit

Price: $120

Description: More snap-together, codable robot trucks that kids get to build and control. These can be programmed either via posing and recording, or using Ubtech’s drag-and-drop, block-based Blockly coding program. The Shenzhen-based company, which has been in the STEM game for several years, offers a range of other kits in the same Jimu kit series — such as this similarly priced UnicornBot and its classic MeeBot Kit, which can be expanded via the newer Animal Add-on Kit

Age: 8+

Product: Dot Creativity Kit

Price: $80

Description: San Francisco-based Wonder Workshop offers a kid-friendly blend of controllable robotics and DIY craft-style projects in this entry-level Dot Creativity Kit. Younger kids can play around and personalize the talkative connected device. But the startup sells a trio of chatty robots all aimed at encouraging children to get into coding. Next in line there’s Dash ($150), also for 6+ year olds. Then Cue ($200) for 11+. The startup also has a growing range of accessories to expand the bots’ (programmable) functionality — such as this Sketch Kit ($40) which adds a few arty smarts to Dash or Cue.

With Dot, younger kids play around using a suite of creative apps to control and customize their robot and tap more deeply into its capabilities, with the apps supporting a range of projects and puzzles designed to both entertain them and introduce basic coding concepts.

Age: 6+

Powered by WPeMatico

When China’s Invictus Gaming defeated European squad Fnatic in the League of Legends 2018 finals this past Saturday, China’s social media platforms became awash in ecstasy and pride.

“It’s like winning an Olympic gold, a teenage dream come true,” writes one thirty-something audience of the competition on his WeChat feed.

Many others share that sentiment. So far, the hashtag #IG冠军, which means “IG the champion,” has generated over one million threads on Weibo, China’s equivalent of Twitter with over four million monthly active users. This is a critical moment for China’s first-generation of players who grew up under parents and teachers who too easily dismissed all kinds of video games.

IG’s victory marks the first time a Chinese team has won the world championship for LoL – fondly called so by fans – the world’s most played PC game according to research firm Newzoo. The role-playing and monster-slaying title is run by Riot Games Inc, a Los Angeles-headquartered studio that WeChat operator Tencent fully bought out in 2015.

It wasn’t just gamers and the youth cheering for IG. Chinese mainstream media also rushed to congratulate. An op-ed from the communist party paper Guangming Daily called IG’s victory “an alternative path to the national sports dream.”

China has a history of obsessing over sports, evident in its generous spending on the Summer Olympics back in 2008 and the upcoming 2022 Winter Olympics. Now esports – or competitive video gaming – as an officially recognized sporting event, is gaining ground among policymakers.

Esports in China has grown from a 53.2 billion yuan ($7.72 billion) industry in 2016 into one that’s estimated to earmark 88.7 billion yuan ($12.87 billion) in revenue in 2018, according to research firm Gamma Data. Local officials across the country want a share of the booming market. In some cases, the governments have shelled out billions of yuan to turn their no-name towns into “esports hub” that would house competitions and gaming companies in hope of stimulating local economies.

Private companies have joined in the game, too. Tencent, China’s largest gaming company by revenue, has invested in NYSE-listed Huya and Douyu, two of China’s leading esports livestreaming services. IG itself is an esports organization that Wang Sicong, son of China’s once richest man Wang Jianlin, founded in 2011 and catapulted to today’s stardom.

But China’s relationship with video games overall has always been murky. While the government is rooting for professional gaming, it’s tightening control over leisure ones, condemning game publishers like Tencent for “poisoning” juveniles with blockbuster titles.

“The Chinese government treats esports and leisure games very differently,” a staff in the esports division of a major global gaming studio who asks to remain anonymous told TechCrunch. “I don’t think IG’s victory will cause big changes to the government’s attitude.”

Tencent, which earns two-thirds of its revenue from online gaming, lost $17.5 billion in market valuation when China’s state newspaper slashed its popular Honor of Kings, widely regarded a mobile copycat of LoL. This year, a hiatus in game license approvals again puts pressure on Tencent stock prices and profitability.

For esports and League of Legends alone, however, IG’s glory could mean a brighter future.

“At least now we will see League of Legends’ popularity continue into a couple more years. Esports’ development may also benefit from the event,” suggests the gaming company staff.

Powered by WPeMatico

Messaging app firm Line has given up majority control of its Line Games business after it raised outside financing to expand its collection of titles and go after global opportunities.

The Line Games business was formed earlier this year when Line merged its existing gaming division from NextFloor, the Korea-based game publisher that it acquired in 2017. Now the business has taken on capital from Anchor Equity Partners, which has provided 125 billion KRW ($110 million) in financing via its Lungo Entertainment entity, according to a disclosure from Line.

A Line spokesperson clarified that the deal will see Anchor acquire 144,743 newly created shares to take a 27.55 percent stake in Line Games. That increase means Line Corp’s own shareholding is diluted from 57.6 percent to a minority 41.73 percent stake.

Korea-based Anchor is best known for a number of deals in its homeland, including investments in e-commerce giant Ticket Monster, Korean chat giant Kakao’s Podotree content business and fashion retail group E-Land.

Line operates its eponymous chat app, which is the most popular messaging platform in Japan, Thailand and Taiwan, and also significantly used in Indonesia, but gaming is a major source of income. This year to date, Line has made 28.5 billion JPY ($250 million) from its content division, which is primarily virtual goods and in-app purchases from its social games. That division accounts for 19 percent of Line’s total revenue, and it is a figure that is only better by its advertising unit, which has grossed 79.3 billion JPY, or $700 million, in 2018 to date.

The games business is currently focused on Japan, Korea, Thailand and Taiwan, but it said that the new capital will go toward finding new IP for future titles and identifying games with global potential. It is also open to more strategic deals to broaden its focus.

While Line has always been big on games, Line Games isn’t just building for its own service. The company said earlier this year that it plans to focus on non-mobile platforms, which will include the Nintendo Switch among others consoles.

That comes from the addition of NextFloor, which is best known for titles like Dragon Flight and Destiny Child. Dragon Flight has racked up 14 million users since its 2012 launch; at its peak it saw $1 million in daily revenue. Destiny Child, a newer release in 2016, topped the charts in Korea and has been popular in Japan, North America and beyond.

Line went public in 2016 via a dual U.S.-Japan IPO that raised more than $1 billion.

Note: The original version of this article was updated to clarify that Lungo Entertainment is buying newly issued shares.

Powered by WPeMatico

Xiaomi has announced the newest version of its bezel-less Mi Mix family, and it doesn’t sport a notch like its Mi 8 flagship. Indeed, unlike the Mi 8 — which I called one of Xiaomi’s most brazen Apple clones — there’s a lot more to get excited about.

The Mi Mix 3 was unveiled at an event in Beijing and, like its predecessor, Xiaomi boasts that it offers a full front screen. Rather than opting for the near-industry standard notch, Xiaomi has developed a slider that houses its front-facing camera. Vivo and Oppo have done similar using a motorized approach, but Xiaomi’s is magnetic while it can also be programmed for functions such as answering calls.

That array gives it a claimed 93.4 percent screen-to-body ratio and a full 6.4-inch 1080p AMOLED display. The slider, by the way, is good for 300,000 cycles, according to Xiaomi’s lab testing.

The device itself follows the much-lauded Mi Mix aesthetic with a Snapdragon 845 processor and up to 10GB in RAM (!) in the highest-end model. Xiaomi puts plenty of emphasis on cameras. The Mi Mix 3 includes four of them: a 24-megapixel front camera paired with a two-megapixel sensor and on the back, like the Mi 8, a dual camera array with two 12-megapixel cameras.

Xiaomi has also snuck an ‘AI button’ on the left side of the phone, a first for the company. That awakens its Xiao Ai voice assistant, but since it only supports Chinese don’t expect to see that on worldwide models.

The 10GB version — made in partnership with Palace Museum, located at the Forbidden City where the device was launched — also packs 256GB of onboard storage and is priced at RMB 4,999, or $720. That’s in addition to a ceramic design that Xiaomi says is inspired by the museum… better that than a fruity-sounding U.S. company.

That’s the special model, and the more affordable options include 6GB + 128GB for RMB 3,299 ($475), 8GB +128G for RMB 3,599 ($520) and 8GB + 256GB for RMB 3,999 ($575). The company also plans to introduce a 5G version in Europe sometime early next year.

Xiaomi said the phones will go on sale in China from 1 November, there’s no word on international availability or pricing right now.

Powered by WPeMatico

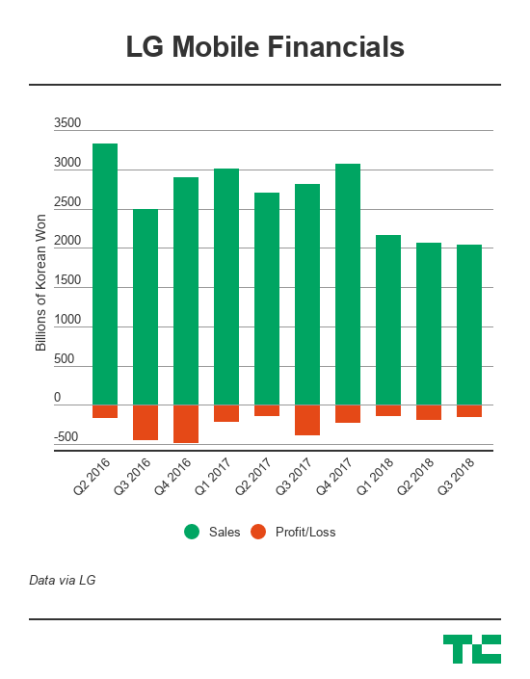

LG remains confident that it can turn the corner for its serially unprofitable mobile business despite the division racking up a loss of over $400 million this year so far.

The Korean company as a whole is having a good year. Following a record six months of profit and revenue in the first half of 2018, the group saw Q3 revenue jump 2.7 percent sequentially to reach 15.43 trillion KRW, or $13.76 billion. Operating profit rose by 45 percent year-on-year to reach 748.8 billion KRW, that’s $667.7 million.

The company’s home entertainment business is the standout performer generating total sales of 3.71 trillion RKW ($3.31 billion) and a 325.1 billion KRW ($289.9 million) profit, with LG Mobile second in terms of revenue. But, the mobile division continues to bleed cash. This time around in Q3, its losses were 146.3 billion RKW, that’s $130.5 million.

That betters large losses for Q3 2016 and 2017 — 436.4 billion KRW and 436.4 billion KRW, respectively — but it means that LG’s mobile division has lost the company $410 million in 2018 so far. But, as the chart below shows, LG has a long way to go before its mobile business stops hurting the group’s overall bottom line and restricting its otherwise impressive growth as a company.

The company played up its performance with a claim that it had weathered challenging global markets — where Chinese brands are competing hard and mobile saturation is weakening consumer demand — by “significantly reduced its operating deficit as a direct result of its business plan and its stronger focus on mid-range products.”

LG recently outed its new V40 ThinQ, a flagship smartphone that packs no fewer than five cameras, and it is optimistic that its launch will boost sales in the final quarter of the year. More widely, it said that the cost-cutting strategy implemented with the appointment of new LG Mobile CEO Hwang Jeong-hwan last November will see it continue to “consolidate and implement a more profitable foundation.”

That strategy has focused around mid-range devices and emerging markets, where LG believes it can offer strong value for money that’ll appeal to consumers in the market for a deal. That explains why mobile division sales are down this year but, crucially, the division is bleeding less capital. Whilst that strategy has helped stem losses, it remains to be seen whether it is the right one to turn the unit profitable.

Powered by WPeMatico

SOSV, a 20-year-old fund with $500 million in assets under management, has been running accelerators for years. Their oldest one, HAX, is the premier hardware accelerator in San Francisco and Shenzhen, and they’ve recently launched a food accelerator in New York and a pair of biology accelerators. Now, however, they’ve just announced DLab, a crypto accelerator that is paired with Cardano to build out distributed apps and solutions.

It is led by Nick Plante, a programmer integral in drafting the JOBS Act and who co-founded Wefunder, a successful crowdfunding platform.

“We can only make this sort of commitment to ecosystems we feel are incredibly compelling; it takes a substantial amount of dedication, education, staffing, and of course the long-term financial commitment to support the space and the companies,” said Plante. “We invest in ecosystems that we identify as ‘macro trends’ like disruptive food, life sciences and synthetic biology, Chinese market entry, IoT and robotics… things that will fundamentally alter the way that we live in the next 100 years.”

“Decentralization is clearly a macro trend, in the macro sense. What’s happening with blockchain and digital ledger technologies has the potential to upend some of the most basic economic incentives that lie beneath the things we do every day; to affect the ways that humans collaborate, identify, trust, govern, and bring new ideas to life… it underlies all of it,” he said.

DLab supplies up to $200,000 in pre-seed funding as well as perks from the SOSV global network of accelerators. They are also offering fellowships in partnership with Cardano to work with projects that would further blockchain research.

“Through last year and the start of this year we kept watching the blockchain ecosystem do some amazing things — along with some criminal things. The surveys and reports about the fraud rates of ICOs and other unpleasantness kept underlining our concerns report after report. The potential for the big economic shifts I mentioned earlier were clearly here but there were so, so many problems; there was a real need for education, for curation, and for proper governance and incentive structures to be put in place,” said Plante.

The group is accepting applications now for a January cohort. The group invests in 150 startups per year, a heady number in these cash-poor times.

Powered by WPeMatico

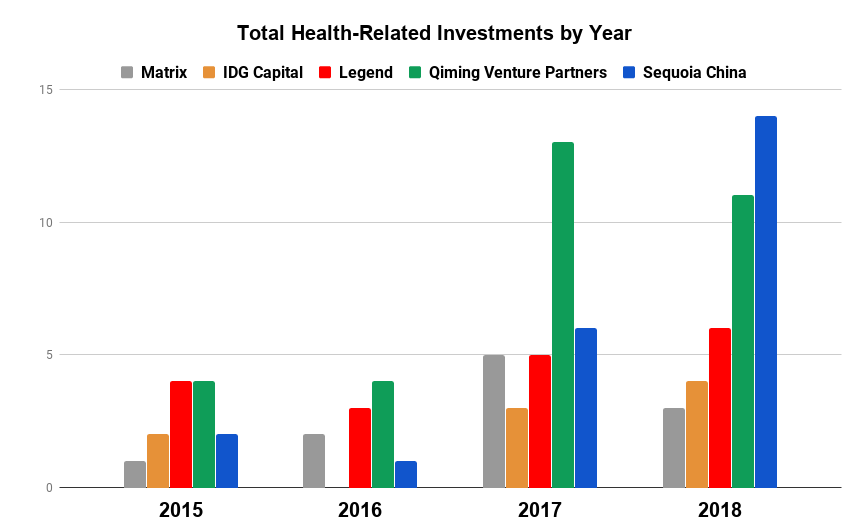

Silicon Valley is in the midst of a health craze, and it is being driven by “Eastern” medicine.

It’s been a record year for US medical investing, but investors in Beijing and Shanghai are now increasingly leading the largest deals for US life science and biotech companies. In fact, Chinese venture firms have invested more this year into life science and biotech in the US than they have back home, providing financing for over 300 US-based companies, per Pitchbook. That’s the story at Viela Bio, a Maryland-based company exploring treatments for inflammation and autoimmune diseases, which raised a $250 million Series A led by three Chinese firms.

Chinese capital’s newfound appetite also flows into the mainland. Business is booming for Chinese medical startups, who are also seeing the strongest year of venture investment ever, with over one hundred companies receiving $4 billion in investment.

As Chinese investors continue to shift their strategies towards life science and biotech, China is emphatically positioning itself to be a leader in medical investing with a growing influence on the world’s future major health institutions.

We like to talk about things we can interact with or be entertained by. And so as nine-figure checks flow in and out of China with stunning regularity, we fixate on the internet giants, the gaming leaders or the latest media platform backed by Tencent or Alibaba.

However, if we follow the money, it’s clear that the top venture firms in China have actually been turning their focus towards the country’s deficient health system.

A clear leader in China’s strategy shift has been Sequoia Capital China, one of the country’s most heralded venture firms tied to multiple billion-dollar IPOs just this year.

Historically, Sequoia didn’t have much interest in the medical sector. Health was one of the firm’s smallest investment categories, and it participated in only three health-related deals from 2015-16, making up just 4% of its total investing activity.

Recently, however, life sciences have piqued Sequoia’s fascination, confirms a spokesperson with the firm. Sequoia dove into six health-related deals in 2017 and has already participated in 14 in 2018 so far. The firm now sits among the most active health investors in China and the medical sector has become its second biggest investment area, with life science and biotech companies accounting for nearly 30% of its investing activity in recent years.

Health-related investment data for 2015-18 compiled from Pitchbook, Crunchbase, and SEC Edgar

There’s no shortage of areas in need of transformation within Chinese medical care, and a wide range of strategies are being employed by China’s VCs. While some investors hope to address influenza, others are focused on innovative treatments for hypertension, diabetes and other chronic diseases.

For instance, according to the Chinese Journal of Cancer, in 2015, 36% of world’s lung cancer diagnoses came from China, yet the country’s cancer survival rate was 17% below the global average. Sequoia has set its sights on tackling China’s high rate of cancer and its low survival rate, with roughly 70% of its deals in the past two years focusing on cancer detection and treatment.

That is driven in part by investments like the firm’s $90 million Series A investment into Shanghai-based JW Therapeutics, a company developing innovative immunotherapy cancer treatments. The company is a quintessential example of how Chinese VCs are building the country’s next set of health startups using their international footprints and learnings from across the globe.

Founded as a joint-venture offshoot between US-based Juno Therapeutics and China’s WuXi AppTec, JW benefits from Juno’s experience as a top developer of cancer immunotherapy drugs, as well as WuXi’s expertise as one of the world’s leading contract research organizations, focusing on all aspects of the drug R&D and development cycle.

Specifically, JW is focused on the next-generation of cell-based immunotherapy cancer treatments using chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) technologies. (Yeah…I know…) For the WebMD warriors and the rest of us with a medical background that stopped at tenth-grade chemistry, CAR-T essentially looks to attack cancer cells by utilizing the body’s own immune system.

Past waves of biotech startups often focused on other immunologic treatments that used genetically-modified antibodies created in animals. The antibodies would effectively act as “police,” identifying and attaching to “bad guy” targets in order to turn off or quiet down malignant cells. CAR-T looks instead to modify the body’s native immune cells to attack and kill the bad guys directly.

Chinese VCs are investing in a wide range of innovative life science and biotech startups. (Photo by Eugeneonline via Getty Images)

The international and interdisciplinary pedigree of China’s new medical leaders not only applies to the organizations themselves but also to those running the show.

At the helm of JW sits James Li. In a past life, the co-founder and CEO held stints as an executive heading up operations in China for the world’s biggest biopharmaceutical companies including Amgen and Merck. Li was also once a partner at the Silicon Valley brand-name investor, Kleiner Perkins.

JW embodies the benefits that can come from importing insights and expertise, a practice that will come to define the companies leading the medical future as the country’s smartest capital increasingly finds its way overseas.

Despite heavy investment by China’s leading VCs, Silicon Valley is doubling down in the US health sector. (AFP PHOTO / POOL / JASON LEE)

Innovation in medicine transcends borders. Sickness and death are unfortunately universal, and groundbreaking discoveries in one country can save lives in the rest.

The boom in China’s life science industry has left valuations lofty and cross-border investment and import regulations in China have improved.

As such, Chinese venture firms are now increasingly searching for innovation abroad, looking to capitalize on expanding opportunities in the more mature US medical industry that can offer innovative technologies and advanced processes that can be brought back to the East.

In April, Qiming Venture Partners, another Chinese venture titan, closed a $120 million fund focused on early-stage US healthcare. Qiming has been ramping up its participation in the medical space, investing in 24 companies over the 2017-18 period.

New firms diving into the space hasn’t frightened the Bay Area’s notable investors, who have doubled down in the US medical space alongside their Chinese counterparts.

Partner directories for America’s most influential firms are increasingly populated with former doctors and medically-versed VCs who can find the best medical startups and have a growing influence on the flow of venture dollars in the US.

At the top of the list is Krishna Yeshwant, the GV (formerly Google Ventures) general partner leading the firm’s aggressive push into the medical industry.

Krishna Yeshwant (GV) at TechCrunch Disrupt NY 2017

A doctor by trade, Yeshwant’s interest runs the gamut of the medical spectrum, leading investments focusing on anything from real-time patient care insights to antibody and therapeutic technologies for cancer and neurodegenerative disorders.

Per data from Pitchbook and Crunchbase, Krishna has been GV’s most active partner over the past two years, participating in deals that total over a billion dollars in aggregate funding.

Backed by the efforts of Yeshwant and select others, the medical industry has become one of the most prominent investment areas for Google’s venture capital arm, driving roughly 30% of its investments in 2017 compared to just under 15% in 2015.

GV’s affinity for medical-investing has found renewed life, but life science is also part of the firm’s DNA. Like many brand-name Valley investors, GV founder Bill Maris has long held a passion for the health startups. After leaving GV in 2016, Maris launched his own fund, Section 32, focused specifically on biotech, healthcare and life sciences.

In the same vein, life science and health investing has been part of the lifeblood for some major US funds including Founders Fund, which has consistently dedicated over 25% of its deployed capital to the space since at least 2015.

The tides may be changing, however, as the recent expansion of oversight for the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) may severely impact the flow of Chinese capital into areas of the US health sector.

Under its extended purview, CFIUS will review – and possibly block – any investment or transaction involving a foreign entity related to the production, design or testing of technology that falls under a list of 27 critical industries, including biotech research and development.

The true implications of the expanded rules will depend on how aggressively and how often CFIUS exercises its power. But a lengthy review process and the threat of regulatory blocks may significantly increase the burden on Chinese investors, effectively shutting off the Chinese money spigot.

Regardless of CFIUS, while China’s active presence in the US health markets hasn’t deterred Valley mainstays, with a severely broken health system and an improved investment environment backed by government support, China’s commitment to medical innovation is only getting stronger.

Deficiencies in China’s health sector has historically led to troublesome outcomes. Now the government is jump-starting investment through supportive policy. (Photo by Alexander Tessmer / EyeEm via Getty Images)

They say successful startups identify real problems that need solving. Marred with inefficiencies, poor results, and compounding consumer frustration, China’s health industry has many.

Outside of a wealthy few, citizens are forced to make often lengthy treks to overcrowded and understaffed hospitals in urban centers. Reception areas exist only in concept, as any open space is quickly filled by hordes of the concerned, sick, and fearful settling in for wait times that can last multiple days.

If and when patients are finally seen, they are frequently met by overworked or inexperienced medical staff, rushing to get people in and out in hopes of servicing the endless line behind them.

Historically, when patients were diagnosed, treatment options were limited and ineffective, as import laws and affordability issues made many globally approved drugs unavailable.

As one would assume, poor detection and treatment have led to problematic outcomes. Heart disease, stroke, diabetes and chronic lung disease accounts for 80% of deaths in China, according to a recent report from the World Bank.

Recurring issues of misconduct, deception and dishonesty have amplified the population’s mounting frustration.

After past cases of widespread sickness caused by improperly handled vaccinations, China’s vaccine crisis reached a breaking point earlier this year. It was revealed that 250,000 children had been given defective and fallacious rabies vaccinations, a fact that inspectors had discovered months prior and swept under the rug.

Fracturing public trust around medical treatment has serious, potentially destabilizing effects. And with deficiencies permeating nearly all aspects of China’s health and medical infrastructure, there is a gaping set of opportunities for disruptive change.

In response to these issues, China’s government placed more emphasis on the search for medical innovation by rolling out policies that improve the chances of success for health startups, while reducing costs and risk for investors.

Billions of public investment flooded into the life science sector, and easier approval processes for patents, research grants, and generic drugs, suddenly made the prospect of building a life science or biotech company in China less daunting.

For Chinese venture capitalists, on top of financial incentives and a higher-growth local medical sector, loosening of drug import laws opened up opportunities to improve China’s medical system through innovation abroad.

Liquidity has also improved due to swelling global interest in healthcare. Plus, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange recently announced changes to allow the listing of pre-revenue biotech companies.

The changes implemented across China’s major institutions have effectively provided Chinese health investors with a much broader opportunity set, faster growth companies, faster liquidity, and increased certainty, all at lower cost.

However, while the structural and regulatory changes in China’s healthcare system has led to more medical startups with more growth, it hasn’t necessarily driven quality.

US and Western investors haven’t taken the same cross-border approach as their peers in Beijing. From talking with those in the industry, the laxity of the Chinese system, and others, have made many US investors weary of investing in life science companies overseas.

And with the Valley similarly stepping up its focus on startups that sprout from the strong American university system, bubbling valuations have started to raise concern.

But with China dedicating more and more billions across the globe, the country is determined to patch the massive holes in its medical system and establish itself as the next leader in international health innovation.

Powered by WPeMatico

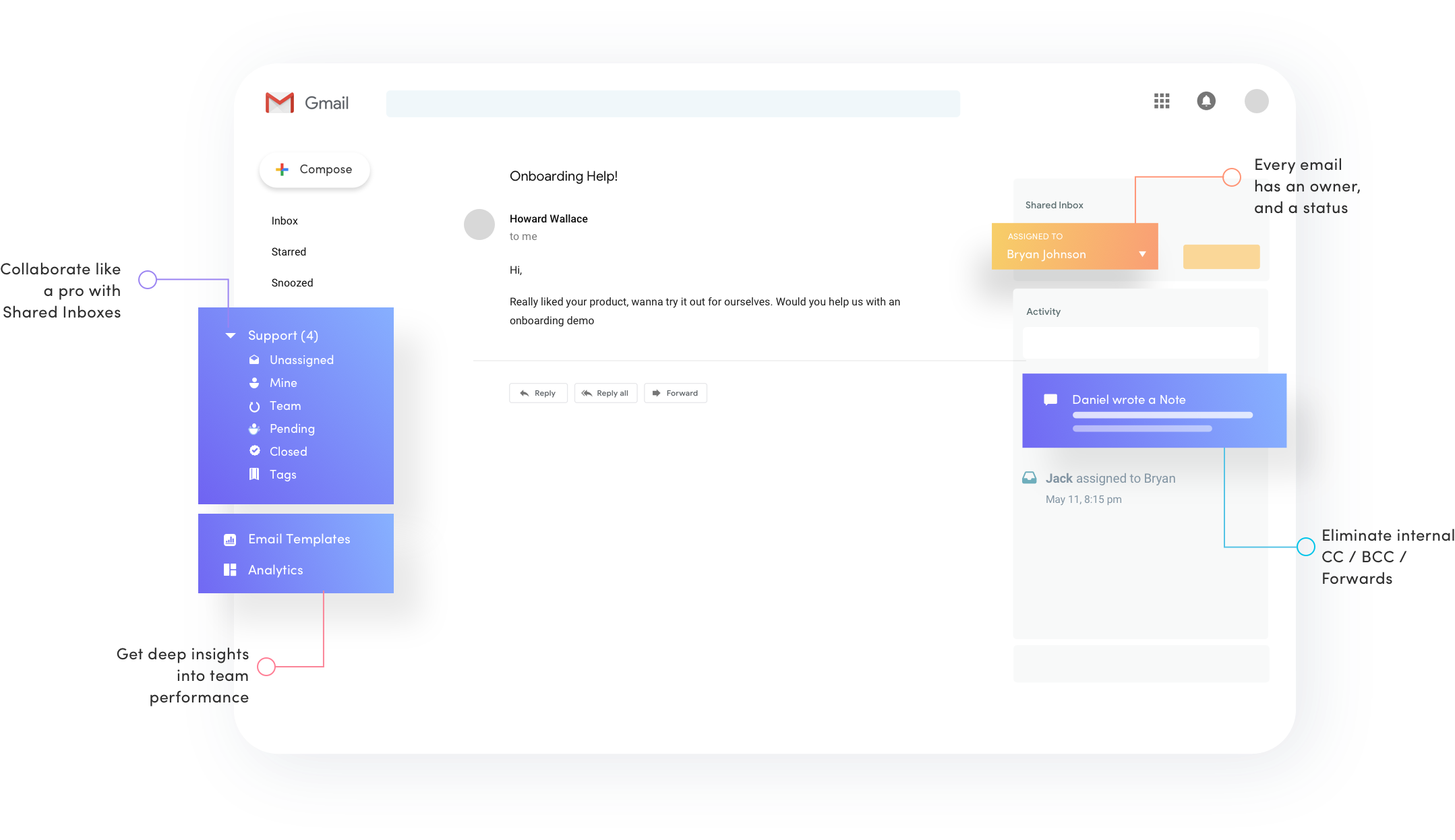

Meet Hiver, a service that lets you collaborate on generic email addresses, such as jobs@yourcompany.com, support@, sales@, etc. Hiver isn’t the only company working on shared inboxes. But compared to Front, everything happens in Gmail directly.

To be fair, Front has been doing a fantastic job when it comes to multiplayer email — and the company has been doing great. Front is a new email client that lets you work together on your inbound emails.

But many teams don’t necessarily want to use a brand new email client. Some people love the Gmail interface so much that they don’t even think about switching to something else.

Hiver is a Google Chrome extension that adds a bunch of feature to your Gmail inbox. In addition to your personal inbox, you can now access shared inboxes with other people in your team. You can then assign an email to one of your coworkers and see what everybody is working on.

If you need help in order to reply to a tedious email, you can write a note in the right column and notify your teammates using @-mentions. All your comments live in this separate column so that you don’t clutter your email thread with forwards and CCs.

Whenever someone starts replying, Hiver shows a collision alert so that customers don’t get two replies. You can also use templates for faster replies, send emails later and share drafts to get another pair of eyes.

More recently, Hiver added automation with simple if/then rules to assign conversations to the right person and categorize your emails automatically.

If you’ve used Front in the past, those features will sound familiar as you can do all of this in Front, and much more. But it turns out that some companies really wanted a “Front for Gmail”.

Hiver just raised a $4 million funding round from Kalaari Capital and Kae Capital. The company is based in India and has 50 employees already. A thousand companies are currently using Hiver, such as Hubspot, Vacasa, Pinterest and Lyft. Most of Hiver’s clients are based in the U.S.

Building a product on top of Gmail creates some limitations. For instance, you’ll have to remain a G Suite customer in order to keep using Hiver. Hiver also works better on desktop. The company has mobile apps, but they are still a bit basic so far.

Hiver uses a software-as-a-service approach. Plans start at $14 per user per month, and you need to pay more for automations, Salesforce integration and more.

Powered by WPeMatico

Photographer: Daro Sulakauri/Bloomberg

According to a new study conducted by the Center for American Entrepreneurship and NYU’s Shack Institute of Real Estate, the US may be losing its competitive advantage as the dominant nucleus of the startup and venture capital universe.

The analysis, led by senior Brookings Institution fellow Ian Hathaway and “Rise of the Creative Class” author Richard Florida, examines the flow of venture capital over 100,000 deals from 2005 to 2017 and details how the historically US-centric practice of venture capital has become a global phenomenon.

While the US still appears to produce the largest amount of venture activity in the world, America’s share of the global pie is falling dramatically and doing so quickly.

In the mid-90s, the US accounted for more than 95% of global venture capital investment. By 2012, this number had fallen to 70%. At the end of 2017, the US share of total venture investment had fallen to just 50%.

Over the last decade, non-US countries have propelled growth in the global startup and venture economy, which has swelled from $50 billion to over $170 billion in size. In particular, China, India and the UK now account for a third of global venture deal count and dollars – 2-3x the share held ten years ago. And with VC dollars increasingly circulating into modernizing Asia-Pac and European cities, the researchers found that the erosion in the US share of venture capital is trending in the wrong direction.

We’ve spent the summer discussing the notion of Silicon Valley reaching its parabolic peak – Observing the “rise of the rest” across smaller American tech hubs. In reality, the data reveals a “rise in the rest of the world”, with startup ecosystems outside the US growing at a faster pace than most US hubs.

The Bay Area remains the world’s preeminent beneficiary of VC investment, and New York, Los Angeles, and Boston all find themselves in the top ten cities contributing to global venture growth. However, only six of the top 20 cities are located in the US, while 14 are in Asia or Europe. At the individual level, only two American cities crack the top 20 fastest growing startup hubs.

Still, the authors found the bulk of VC activity remains highly concentrated in a small number of incumbent startup cities. More than 50% of all global venture capital deployed can be attributed to only six cities and half of the growth in VC activity over the last five years can be attributed to just four cities. Despite the growing number of ecosystems playing a role in venture decisions, the dominant incumbent startup hubs hold a firm grip on the majority of capital deployed.

Unsurprisingly, the largest contributor to the globalization of venture capital and the slimming share of the US is the rapid escalation of China’s startup ecosystem.

In the last three years, China has captured nearly a fourth of total VC investment. Since 2010, Beijing contributed more to VC deployment growth than any other city, while three other Chinese cities (Shanghai, Hangzhou, Shenzhen) fell in the top 15.

A major part of China’s ascension can be tied to the idiosyncratic rise of late-stage “mega deals”, which the study defines as $500 million or more in size. Once an extremely rare occurrence, mega deals now make up a significant portion of all venture dollars deployed. From 2005-2007, only two mega deals took place. From 2010-2012, eight of such deals took place. From 2015-2017, there were 80 global mega deals, representing a fifth of the total venture capital activity. Chinese cities accounted for half of all mega deal investment over the same period.

It’s not all bad for the US, with the study highlighting continued ecosystem growth in established US hubs and leading roles for non-valley markets in NY, LA, and Boston.

And the globalization of the startup and venture economy is by no means a “bad thing”. In fact, access to capital, the spread of entrepreneurial spirit, and stronger global economic development and prosperity is almost unquestionably a “good thing.”

However, the US’ share of venture-backed startups is falling, and the US losing its competitive advantage in the startup and venture capital market could have major implications for its future as a global economic leader. Five of the six largest US companies were previously venture-backed startups and now provide a combined value of around $4 trillion.

The intense competition for talent marks another major challenge for the US who has historically been a huge beneficiary of foreign-born entrepreneurs. With the rise of local ecosystems across the globe, entrepreneurs no longer have to flock to the US to build their companies or have access to venture capital. The problem attracting entrepreneurs is compounded by notoriously unfriendly US visa policies – not to mention recent harsh rhetoric and tension over immigration that make the US a less attractive destination for skilled immigrants.

At a recent speaking event, Florida stated he believed the US’ fading competitive advantage was a greater threat to American economic power than previous collapses seen in the steel and auto industries. A sentiment echoed by Techstars co-founder Brad Feld, who in the report’s forward states, “government leaders should read this report with alarm.”

It remains to be seen whether the train has left the station or if the US can hold on to its position as the world’s venture leader. What is clear is that Silicon Valley is no longer the center of the universe and the geography of the startup and venture capital world is changing.

“The Rise of the Global Startup City: The New Map of Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital” tries to illustrate these tectonic shifts and identifies tiers of global startup cities based on size, growth and balance of VC deals and investments.

Powered by WPeMatico