Fundings & Exits

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

The recovery in value of several high-profile electric car companies could help move yet-private EV manufacturers out of the pit lane and onto the IPO track.

On the heels of NIO’s shocking value appreciation after its recent earnings report, and Tesla’s own public market run, China-based Lixiang Automotive is reported to have filed privately for an IPO in the United States.

Lixiang Automotive is a Beijing-based company that was founded in 2015, according to Crunchbase data. The company has raised north of $1 billion while private, and is said to be valued at just under $3 billion. It most recently raised a $530 million round led by Xing Wang, of Meituan-Dianping fame.

It would not be the first Chinese EV company to go public in the United States, as NIO managed the feat in 2018. But the reported filing shows newfound confidence concerning investor sentiment by the alternative car market’s players and bankers.

To understand the news, we’ll first look at recent happenings from Lixiang’s public peers, and then examine the company itself.

A month ago, the Lixiang Automotive confidential IPO filing would have appeared quixotic. After all, its closest market comparable was flirting with penny-stock status.

NIO was in the tank more than a year after an IPO that proved far from smooth. After going public at $6.26 per share, its equity had traded down to nearly the $1 mark, setting a 52-week low at the terrifying figure of $1.19 per share. However, since then, shares of the unprofitable, cash-strapped EV manufacturer have recovered, trading for $3.84 per share today. Still down from its IPO price, yes, but up more than 200% from its recent all-time lows (a more than tripling in value).

That likely cleared a path for Lixiang Automotive to file, albeit privately. Reuters broke the news of its IPO prospects.

Tesla’s ascent also helped. After some oddly normal (for Tesla) drama cooled, the company’s shares have come back a long way. From 52-week lows of $176.99, Elon’s car company is now worth $445.25. Shares of Tesla are up 150% from their lows, a more than doubling in market cap. Investors appeared to find its earnings and delivery totals (and progress on its Chinese factory) heartening.

For Lixiang Automotive, the moves showed that U.S. equity markets were warming waters worth testing. Given that it is certainly unprofitable, the opening of a new funding avenue was welcome.

Notably, similar to NIO when it went public, the company is set to debut while its history of actually delivering cars is nascent. NIO went public having delivered cars in the mere hundreds. The firm did note at the time that it had commits north of 10,000 for its cars. During the early days of its IPO I wrote that the company’s limited history of revenue generation made its shares a gamble.

Lixiang is set to go public at a similar level of immaturity. According to Equal Ocean, Lixiang now delivers cars, though it began to ship them just last month:

Chinese electric vehicle manufacturer Lixiang Automotive, formerly known as CHJ, has announced that its EV project ‘Lixiang ONE 2020’ is officially mass-produced at the Changzhou factory and will start mass delivery in early December.

Pre-sales for the car took place in Q4 2019, as well, meaning that the company’s pre-Q4 2019 revenue should wind up looking very light.

If Lixiang does successfully go public it will show that corporate maturity is not a requirement for an IPO. When we do get to see Lixiang’s F-1 filing, we won’t see the history of a company with an obvious path to profits amid quick growth — we’ll see a deeply unprofitable company in the early motion of generating material revenue.

A little bit ago I would have given such an offering slim chance of success. But with NIO on the bounce and Tesla back on form, who knows?

Powered by WPeMatico

A few days before Christmas, TechCrunch caught up with CrowdStrike CEO George Kurtz to chat about his company’s public offering, direct listings and his expectations for the 2020 IPO market. We also spoke about CrowdStrike’s product niche — endpoint security — and a bit more on why he views his company as the Salesforce of security.

The conversation is timely. Of the 2019 IPO cohort, CrowdStrike’s IPO stands out as one of the year’s most successful debuts. As 2020’s IPO cycle is expected to be both busy and inclusive of some of the private market’s biggest names, Kurtz’s views are useful to understand. After all, his SaaS security company enjoyed a strong pricing cycle, a better-than-expected IPO fundraising haul and strong value appreciation after its debut.

Notably, CrowdStrike didn’t opt to pursue a direct listing; after chatting with the CEO of recent IPO Bill.com concerning why his SaaS company also decided on a traditional flotation, we wanted to hear from Kurtz as well. The security CEO called the current conversation around direct listings a “great debate,” before explaining his perspective.

Pulling from a longer conversation, what follows are Kurtz’s four tips for companies gearing up for a public offering, why his company elected chose a traditional public offering over a more exotic method, comments on endpoint security and where CrowdStrike fits inside its market, and, finally, quick notes on upcoming debuts.

The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What’s most important is the fact that when we IPO’d in June of 2019, we started the process three years earlier. And that is the number one thing that I can point to. When [CrowdStrike CFO Burt Podbere] and I went on the road show everybody knew us, all the buy side investors we had met with for three years, the sell side analysts knew us. The biggest thing that I would say is you can’t go on a road show and have someone not know your company, or not know you, or your CFO.

And we would share — as a private company, you share less — but we would share tidbits of information. And we built a level of consistency over time, where we would share something, and then they would see it come true. And we would share something else, and they would see it come true. And we did that over three years. So we built, I believe, trust with the street, in anticipation of, at some point in the future, an IPO.

We spent a lot of time running the company as if it was public, even when we were private. We had our own earnings call as a private company. We would write it up and we would script it.

You’ve seen other companies out there, if they don’t get their house in order it’s very hard to go [public]. And we believe we had our house in order. We ran it that way [which] allowed us to think and operate like a public company, which you want to get out of the way before you come become public. If there’s a takeaway here for folks that are thinking about [going public], run it and act like a public company before you’re public, including simulated earnings calls. And once you become public, you already have that muscle memory.

The third piece is [that] you [have to] look at the numbers. We are in rarified air. At the time of IPO we were the fastest growing SaaS company to IPO ever at scale. So we had the numbers, we had the growth rate, but it really was a combination of preparation beforehand, operating like a public company, […] and then we had the numbers to back it up.

One last point, we had the [total addressable market, or TAM] as well. We have the TAM as part of our story; security and where we play is a massive opportunity. So we had that market opportunity as well.

On this topic, Kurtz told TechCrunch two interesting things earlier in the conversation. First that what many people consider as “endpoint security” is too constrained, that the category includes “traditional endpoints plus things like mobile, plus things like containers, IoT devices, serverless, ephemeral cloud instances, [and] on and on.” The more things that fit under the umbrella of endpoint security, CrowdStrike’s focus, the bigger its market is.

Kurtz also discussed how the cloud migration — something that builds TAM for his company’s business — is still in “the early innings,” going on to say that in time “you’re going to start to see more critical workloads migrate to the cloud.” That should generate even more TAM for CrowdStrike and its competitors, like Carbon Black and Tanium.

Powered by WPeMatico

One Medical, a San Francisco-based primary care startup with tech-infused, concierge services filed for an IPO with the Securities and Exchange Commission today.

Internal medicine doctor Tom Lee founded the startup, now valued at well-over $1 billion dollars, in 2007. Lee exited his company in 2017, leaving it in the hands of former UnitedHealth group executive Amir Rubin.

The startup currently operates 72 health clinics in nine major cities throughout the U.S., with three more markets expected to open in 2020 and has raised just over $500 in venture capital from it’s biggest investor, the Carlyle Group (which owns just over a quarter of shares), Alphabet’s GV, J.P. Morgan and others. Google also incorporates One Medical into its campuses and accounts for about 10% of the company revenue, according to the SEC filing. The filing also mentions the company, which is officially incorporated as 1Life Healthcare Inc. ONEM, now plans to raise about $100 million.

Presumably, this money will help the company improve upon its technology and expand to more markets. We’ve reached out to One Medical for more and so far have only been referred to its wire statement.

According to that statement, One Medical has applied for a listing as ticker symbol, ONEM under its common stock on the Nasdaq Global Select Market.

Powered by WPeMatico

Trussle, the online mortgage broker backed by the likes of Goldman Sachs, LocalGlobe, Finch Capital and Seedcamp, has lost its founding CEO.

Ishaan Malhi, who co-founded the fintech startup five years ago, has resigned with “immediate effect,” according to a rather brief press release issued by Trussle this morning.

The company is now searching for Malhi’s replacement and in the interim says it will be led by Chairman Simon Williams and others in the senior leadership team. “Williams will be supported by co-founder Jonathan Galore who helped establish Trussle in 2015 and remains closely involved in the business,” reads the press release.

Williams joined Trussle’s board in April 2019, and has had a long stint in financial services. He spent nine years at Citigroup, heading up its International Retail Bank, and more recently served as head of HSBC’s Wealth Management group until 2014.

Meanwhile, the departure of Malhi seems rather abrupt, not least as he doesn’t appear to be involved in the recruitment of his successor. As well as resigning from the role of CEO, the Trussle co-founder has resigned from the startup’s board.

Trussle itself declined to provide further detail, with a spokesperson for the company advising that any questions with regards to why Malhi has resigned should be put to him. I pinged Malhi for comment but he declined to take my call having committed to spending the day with family.

However, he did give a statement to The Telegraph newspaper, telling reporter James Cook: “it was my decision to step down.”

More broadly, the story appears to be being spun as a young first-time founder growing a business to a size where more experienced leadership is needed to take it to the next stage. And it’s certainly true that the company has been staffing up in recent months, growing to 120 staff members (as of late November 2019) and bolstering the leadership team.

Along with Williams, Trussle announced in November that it had recruited ex-Wallaby Financial co-founder Todd Zino as CTO, and ex-head of Zoopla content strategy Sebastian Anthony as head of Organic Growth and Product Manager.

At the time of the announcement, Malhi said in a statement that “culture remains to be our competitive advantage” — a culture that has since seen its founding CEO depart abruptly before a replacement has been found.

Although, as one person with inside knowledge of Malhi’s departure framed it, Trussle has been attempting to diversify the startup’s leadership team for a while now and make the company “less of a one-man show.”

What’s also clear is that the online mortgage broker space is a tough one and pretty capital-intensive due to high customer acquisition costs compared to traditional brokers where cross-selling is the norm but cost of operations is greater and less scalable. The promise of the online broker model is that once scale is achieved, lower operational costs will start to offset those higher and fiercely competitive acquisition costs.

In other words, a classic venture/digitisation bet, but one that is yet to pan out definitively.

As another reference point, one source tells me that Trussle is projected to make a £10 million loss in 2019 based on £2 million in revenue. I also understand from sources that the startup recently closed an internal funding round from existing investors — separate from its £13.6 million Series B in May 2018, and that its backers remain bullish. As always, watch this space.

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the gray space in between.

Today we’re adding four new names to the growing $100 million annual recurring revenue (ARR) club. The firms — Sisense, SiteMinder, Monday.com, and Lemonade — add diversity to our current group of yet-private companies which have reached the nine-figure recurring revenue threshold.

Our goal in tracking the companies in this high-flying cohort is to keep tabs on the private firms (often unicorns, it should be said) that could go public if needed. While not every unicorn will or could go public, companies with nine-figure ARR have a clear path to the public markets provided that their economics are in reasonable shape.

And we’ve seen some remarkably efficient companies meet the mark, including Egnyte with just $137.5 million raised, and Braze, with only $175 million on its books. For growth-oriented, venture-backed companies, those are efficient results.

But let’s add a few more members to the club today. Please meet our new centurions, centaurs, or whatever we end up calling them.

Sisense is a business intelligence company that merged with Periscope Data earlier this year. The combined firm has raised just over $200 million, according to Crunchbase, with the lion’s share of that landing in Sisense’s column (about $175 million).

What’s notable about the combination is that the two firms were public about saying that, when brought together, they would have combined ARR of $100 million. That was back in May. Today, Sisense has crested the $100 million mark by itself, according to an interview with TechCrunch. With Periscope added to the mix the company’s total ARR is naturally higher.

Sisense had a few original goals according to CEO Amir Orad, including helping businesses “take complex data and bring it together to get insights.” Its second focus is helping companies “take complex data sets and build [them out] as an analytical application in their products,” he said.

Periscope came into the picture when Orad and the smaller company’s CEO Harry Glaser (now Sisense’s CMO) started talking as friends about their respective markets. According to Orad, Glaser outlined a new sort of organization being built inside some companies that “were not traditional BI teams” or “traditional product teams,” but instead brought together “data engineers and data scientists and very capable individuals who [wanted] to make sense of [the] data sitting in the cloud.” Periscope had built “a very impressive business” supporting those new organizations, with “many hundreds of customers,” Orad said.

That meant that Sisense’s pair of focuses were somewhat two of out three, making the corporate combination an obvious bet.

Regarding what changed as Sisense grew, cresting the $50 million ARR mark and later the $100 million ARR mark, Orad told TechCrunch that what differed was “scale,” saying that at its size “what you do impacts more people, more individuals, more companies, [and] more customers.” (I have interesting notes on how the two companies managed their combination from a culture perspective, let me know if you’d like to read them.)

The first Australian member of the nine-figure ARR club is SiteMinder, which we’re letting in on a technicality; the firm’s ARR figure is in Australian dollars, which works out to around $70 million USD. However, its growth curve appears steep so we’re not too worried about including it a little early from a domestic dollar perspective.

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the gray space in between.

It’s finally 2020, the year that should bring us a direct listing from home-sharing giant Airbnb, a technology company valued at tens of billions of dollars. The company’s flotation will be a key event in this coming year’s technology exit market. Expect the NYSE and Nasdaq to compete for the listing, bankers to queue to take part, and endless media coverage.

Given that that’s ahead, we’re going to take periodic looks at Airbnb as we tick closer to its eventual public market debut. And that means that this morning we’re looking back through time to see how fast the company has grown by using a quirky data point.

Airbnb releases a regular tally of its expected “guest stays” for New Year’s Eve each year, including 2019. We can therefore look back in time, tracking how quickly (or not) Airbnb’s New Year Eve guest tally has risen. This exercise will provide a loose, but fun proxy for the company’s growth as a whole.

Before we look into the figures themselves, keep in mind that we are looking at a guest figure which is at best a proxy for revenue. We don’t know the revenue mix of the guest stays, for example, meaning that Airbnb could have seen a 10% drop in per-guest revenue this New Year’s Eve — even with more guest stays — and we’d have no idea.

So, the cliche about grains of salt and taking, please.

But as more guests tends to mean more rentals which points towards more revenue, the New Year’s Eve figures are useful as we work to understand how quickly Airbnb is growing now compared to how fast it grew in the past. The faster the company is expanding today, the more it’s worth. And given recent news that the company has ditched profitability in favor of boosting its sales and marketing spend (leading to sharp, regular deficits in its quarterly results), how fast Airbnb can grow through higher spend is a key question for the highly-backed, San Francisco-based private company.

Here’s the tally of guest stays in Airbnb’s during New Years Eve (data via CNBC, Jon Erlichman, Airbnb), and their resulting year-over-year growth rates:

In chart form, that looks like this:

Let’s talk about a few things that stand out. First is that the company’s growth rate managed to stay over 100% for as long as it did. In case you’re a SaaS fan, what Airbnb pulled off in its early years (again, using this fun proxy for revenue growth) was far better than a triple-triple-double-double-double.

Next, the company’s growth rate in percentage terms has slowed dramatically, including in 2019. At the same time the firm managed to re-accelerate its gross guest growth in 2019. In numerical terms, Airbnb added 1,000,000 New Year’s Eve guest stays in 2017, 700,000 in 2018, and 800,000 in 2019. So 2019’s gross adds was not a record, but it was a better result than its year-ago tally.

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the gray space in between.

Today, the last day of 2019, we’re taking a second look at Boston. Regular readers of this column will recall that we recently took a peek at Boston’s startup ecosystem, and that we compiled a short countdown of the largest rounds that took place this year in Utah. Today we’re doing the latter with the former.

What follows is a countdown of Boston’s seven largest venture rounds from the year, including details concerning what the company does and who backed it. We’re also taking a shot after each entry at where we think the companies are on the path to going public.

As before, we’re using Crunchbase data for this project (here). And we’re only looking at venture rounds, so no post-IPO action, no grants, no secondaries, no debt, and no private equity-style buyouts.

Ready? Let’s have some fun.

Boston has produced a number of big exits in recent years, like Carbon Black’s IPO, DraftKings’ impending kinda-IPO, Cayan’s billion-dollar exit, and SimpliVity’s huge sale to HP. Despite that, however, Boston is often pigeon-holed as a biotech hotbed with little technology that folks from San Francisco can understand. That’s not really fair, it turns out. There’s plenty of SaaS in Boston.

As you read the list, keep tabs on what percent of the companies included you were already familiar with. These are startups that will to take up more and more media attention as they march towards the public markets. It’s better to know them now than later.

Following the pattern set with Utah, we’ll start at the smallest round of our group and then count up to the largest.

We could actually call the Motif FoodWorks‘ Series A a $117.5 million round as it came in two parts. However, the first tranche was $90 million total and landed in 2019 so that’s our selection for the uses of this post. The company is backed by Fonterra Ventures, Louis Dreyfus Corp, and General Atlantic.

Motif works in the alternative food space, creating things like fake meat and alt-dairy. Given the meteoric rise of Beyond Meat and Impossible Food’s big year, the space is hot. Lots of folks want to eat less meat for ethical or ecological reasons (often the two intertwine). That demand is powering a number of companies forward. Motif is riding a powerful wave.

The company’s known raised capital is encompassed in a large, early-stage round. That means that we won’t see an S-1 from this company for a long, long time.

An email marketing and analytics company, Klaviyo gets point for having a pricing page that actually makes sense — a rarity in the enterprise software world.

The Boston-based company was founded in 2012 and, according to Crunchbase data, has raised a total of $158.5 million. It raised just $8.5 million in total (across a small Seed round and a modest Series A) before its mega-round. How did it manage to raise such an enormous infusion in one go? As TechCrunch reported when the round was announced in April of this year:

The company is growing in leaps and bounds. It currently has 12,000 customers. To put that into perspective, it had just 1,000 at the end of 2016 and 5,000 at the end of 2017.

That will get the attention of anyone with a checkbook. The Summit Partners and Astral Capital-backed company has huge capital reserves for what we presume is the first time in its life. That means it’s not going public any time soon, even if our back-of-the-napkin math puts it comfortably over the $100 million ARR mark (warning: estimates were used in the creation of that number).

ezCater is an online catering marketplace. That’s an attractive business, it turns out, as evinced by the Boston company’s funding history. The startup has raised over $300 million to date according to Crunchbase, including capital from Insight Partners, ICONIQ Capital, Wellington Management, GIC, and Lightspeed.

The company’s 2019 $150 million Series D-1 that valued the company at $1.25 billion wasn’t its only nine-figure round; ezCater’s 2018 Series D was also over the mark, weighing in at $100 million.

When might the Northeast unicorn go public? An interview earlier this year put 2021 on the map as a target for the startup. That’s ages away from now, sadly, as I’d love to know how the company’s gross margin have changed since it started raising venture capital in huge gulps.

Cybereason competes with CrowdStrike. That’s a good space to play in as CrowStrike went public earlier this year, and it went pretty well. That fact makes the Boston’s endpoint security shop’s $200 million investment pretty easy to understand. Indeed, CrowdStrike went public to great effect in June of 2019; Cybereason announced its huge round two months later in August. Surprise.

As far as backing goes, Cybereason has friends at SoftBank, with the Japanese conglomerate leading its Series C, D, and E rounds. Prior leads include CRV and Spark Capital.

The market is hot for SaaS-y security companies, meaning that there is natural pressure on Cybereason to go public. The firm, worth a flat $1.0 billion post-money after its latest round, is therefore an obvious IPO candidate for 2020. If it has the guts, that is. With SoftBank in your corner, there’s probably always another $100 million lying around you can snap up to avoid filing. (More from CrowdStrike’s CEO coming later this week on the 2019 and 2020 IPO markets, by the way. Stay tuned.)

DataRobot does enterprise AI, allowing companies to use computer intelligence to help their flesh-and-blood staffers do more, more quickly. That’s the gist I got from learning what I could this morning, but as with all things AI I cannot tell you what’s real and what’s not.

Given its investor list, though, I’d bet that DataRobot is onto something. New Enterprise Associates led its 2014, 2016, and 2017 Series A, B, and C rounds. Meritech and Sapphire took over at the Series D, with Sapphire heroing DataRobot’s $206 million Series E. That round creatively valued the firm at, you guessed it, $1.0 billion according to Crunchbase.

DataRobot is hiring like mad (343 open positions as of this morning) and buying other companies (three in 2019). Flush with its largest round ever, I don’t see the company in a hurry to go public. That means no 2020 debut unless it’s monetizing faster than expected.

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the gray space in between.

It’s the second to last day of 2019, meaning we’re very nearly out of time this year; our space for repretrospection is quickly coming to a close. Before we do run out of hours, however, I wanted to peek at some data that former Kleiner Perkins investor and Packagd founder Eric Feng recently compiled.

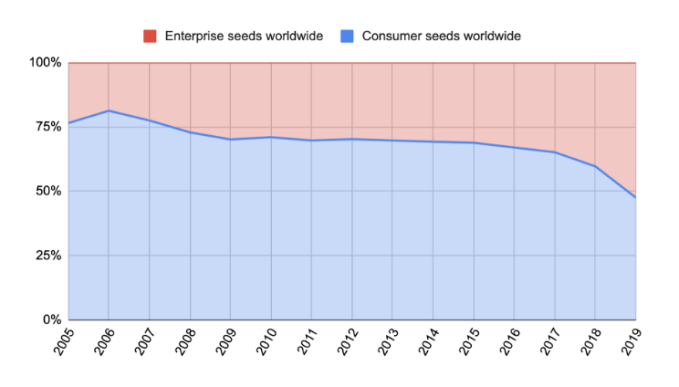

Feng dug into the changing ratio between enterprise-focused Seed deals and consumer-oriented Seed investments over the past decade or so, including 2019. The consumer-enterprise split, a loose divide that cleaves the startup world into two somewhat-neat buckets, has flipped. Feng’s data details a change in the majority, with startups selling to other companies raising more Seed deals than upstarts trying to build a customer base amongst folks like ourselves in 2019.

The change matters. As we continue to explore new unicorn creation (quick) and the pace of unicorn exits (comparatively slow), it’s also worth keeping an eye on the other end of the startup lifecycle. After all, what happens with Seed deals today will turn into changes to the unicorn market in years to come.

Let’s peek at a key chart from Feng, talk about Seed deal volume more generally, and close by positing a few reasons (only one of which is Snap’s IPO) as to why the market has changed as much as it has for the earliest stage of startup investing.

Feng’s piece, which you can read here, tracks the investment patterns of startup accelerator Y Combinator against its market. We care more about total deal volume, but I can’t recommend the dataset enough if you have the time.

Concerning the universe of Seed deals, here’s Feng’s key chart:

Chart via Eric Feng / Medium

As you can see, the chart shows that in the pre-2008 era, Seed deals were amply skewed towards consumer-focused Seed investments. A new normal was found after the 2008 crisis, with just a smidge under 75% of Seed deals focused on selling to the masses for nearly a decade.

In 2016, however, a new trend emerged: a gradual decline in consumer Seed deals and a shift towards enterprise investments.

This became more pronounced in 2017, sharper in 2018, and by 2019 fewer than half of Seed deals focused on consumers. Now, more than half are targeting other companies as their future customer base. (Y Combinator, as Feng notes, got there first, making a majority of investments into enterprise startups since 2010, with just a few outlying classes.)

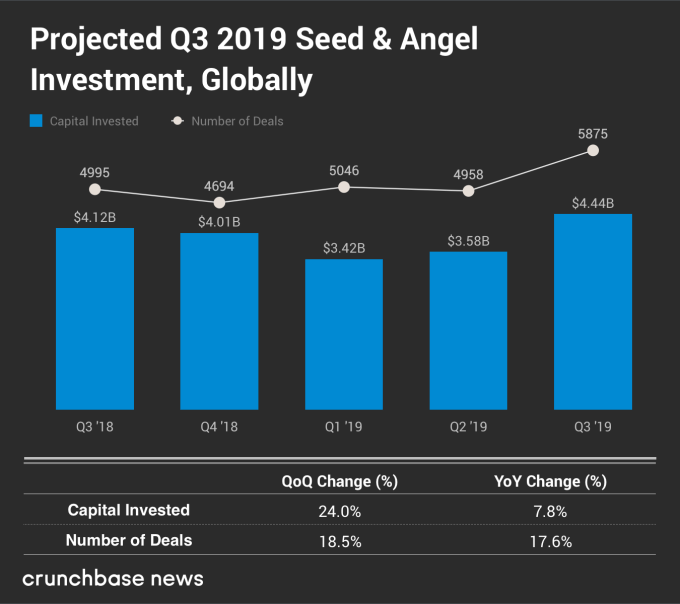

This flip comes as Seed deals sit at the 5,000-per-quarter mark. As Crunchbase News published as Q3 2019 ended, global Seed volume is strong:

So, we’re seeing a healthy number of deals as the consumer-enterprise ratio changes. This means that the change to more enterprise deals as a portion of all Seed investments isn’t predicated on their number holding steady while Seed deals dried up. Instead, enterprise deals are taking a rising share while volume appears healthy.

Now we get to the fun stuff; why is this happening?

As with many trends long in the making, there is no single reason why Seed investors have changed up their investing patterns. Instead, there are likely a myriad that added up to the eventual change. I’m going to ping a number of Seed investors this week to get some more input for us to chew on, but there are some obvious candidates that we can discuss today.

In no particular order, here are a few:

Powered by WPeMatico

VMware is closing the year with a significant new component in its arsenal. Today it announced it has closed the $2.7 billion Pivotal acquisition it originally announced in August.

The acquisition gives VMware another component in its march to transform from a pure virtual machine company into a cloud native vendor that can manage infrastructure wherever it lives. It fits alongside other recent deals like buying Heptio and Bitnami, two other deals that closed this year.

They hope this all fits neatly into VMware Tanzu, which is designed to bring Kubernetes containers and VMware virtual machines together in a single management platform.

“VMware Tanzu is built upon our recognized infrastructure products and further expanded with the technologies that Pivotal, Heptio, Bitnami and many other VMware teams bring to this new portfolio of products and services,” Ray O’Farrell, executive vice president and general manager of the Modern Application Platforms Business Unit at VMware, wrote in a blog post announcing the deal had closed.

Craig McLuckie, who came over in the Heptio deal and is now VP of R&D at VMware, told TechCrunch in November at KubeCon that while the deal hadn’t closed at that point, he saw a future where Pivotal could help at a professional services level, as well.

“In the future when Pivotal is a part of this story, they won’t be just delivering technology, but also deep expertise to support application transformation initiatives,” he said.

Up until the closing, the company had been publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange, but as of today, Pivotal becomes a wholly owned subsidiary of VMware. It’s important to note that this transaction didn’t happen in a vacuum, where two random companies came together.

In fact, VMware and Pivotal were part of the consortium of companies that Dell purchased when it acquired EMC in 2015 for $67 billion. While both were part of EMC and then Dell, each one operated separately and independently. At the time of the sale to Dell, Pivotal was considered a key piece, one that could stand strongly on its own.

Pivotal and VMware had another strong connection. Pivotal was originally created by a combination of EMC, VMware and GE (which owned a 10% stake for a time) to give these large organizations a separate company to undertake transformation initiatives.

It raised a hefty $1.7 billion before going public in 2018. A big chunk of that came in one heady day in 2016 when it announced $650 million in funding led by Ford’s $180 million investment.

The future looked bright at that point, but life as a public company was rough, and after a catastrophic June earnings report, things began to fall apart. The stock dropped 42% in one day. As I wrote in an analysis of the deal:

The stock price plunged from a high of $21.44 on May 30th to a low of $8.30 on August 14th. The company’s market cap plunged in that same time period falling from $5.828 billion on May 30th to $2.257 billion on August 14th. That’s when VMware admitted it was thinking about buying the struggling company.

VMware came to the rescue and offered $15.00 a share, a substantial premium above that August low point. As of today, it’s part of VMware.

Powered by WPeMatico

Over the weekend, media and digital brand holding company IAC announced that it had agreed to buy Care.com, which describes itself as “the world’s largest online family care platform,” in a deal valued at about $500 million. Despite being the best-known marketplace in the United States for finding child and senior caregivers, Care.com has spent the past nine months dealing with the fallout from a Wall Street Journal investigative article that detailed potentially dangerous gaps in its vetting process. The company’s issues not only highlight the problems with scaling a marketplace created to find caregivers for the most vulnerable members of society, but also the United States’ childcare crisis.

Childcare in the United States is weighed down with many issues and arguably no one platform can fix it, no matter how large or well-known. Over the past year and a half, however, several startups dedicated to fixing specific challenges have raised funding, including Wonderschool, Kinside and Winnie.

IAC and Care.com’s announcement came at the end of a year when more media attention has been paid to the difficulties American parents face in finding and affording childcare, and how that contributes to gender disparities, falling birthrates and other social issues. The U.S. is the only industrialized nation in the world without mandated paid parental leave and childcare is one of the biggest expenses for families. Several Democratic presidential candidates, including Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, have made universal childcare part of their platform and business leaders like Alexis Ohanian are using their clout to advocate for better family leave policies.

But the issue has already created deep structural problems. From an economic perspective, a September 2018 study by ReadyNation and Council for a Strong America estimated that annually, the 11 million working parents in the United States lose a total of $37 billion in earnings because they lack adequate childcare. Businesses in turn lose a total of $13 billion a year as a result, while the impact on lower income and sales tax reduces tax revenues by $7 billion. Many parents change their career trajectories after they have children, even if they did not plan to. For example, a study published earlier this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that 43% of women and 23% of men in STEM change fields, switch to part-time work or leave the workforce.

Powered by WPeMatico