Fundings & Exits

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the gray space in between.

Today we’re peeking at what’s gone on in the world of altcoins recently, the other cryptocurrencies aside from bitcoin.

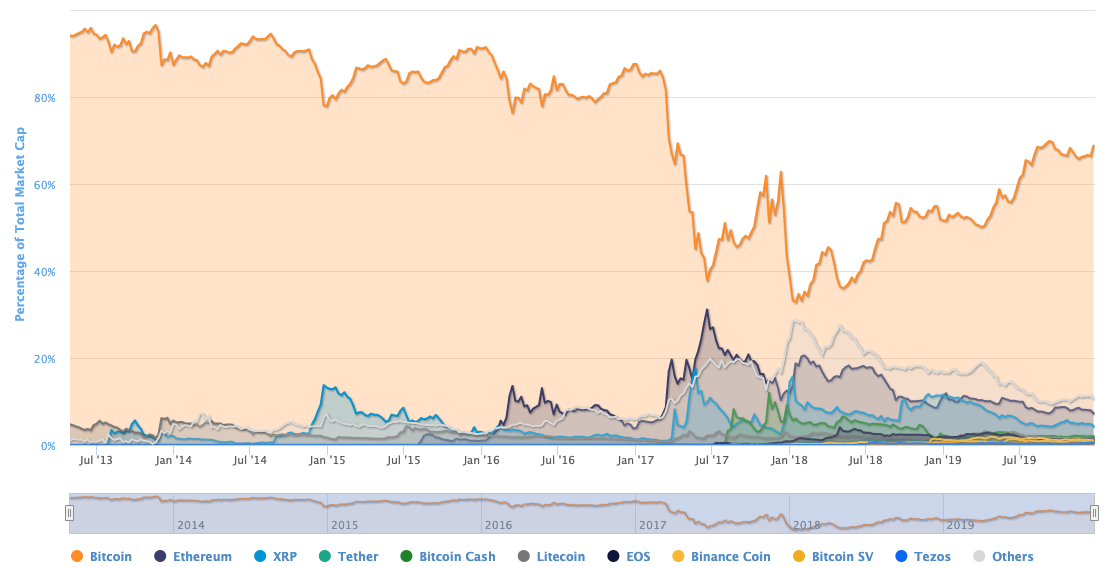

As 2016 came to a close, altcoins like ether and XRP saw their value soar. Toward the end of 2016 through early 2018, bitcoin’s relative share of the aggregate value of all cryptocurrencies fell to about a third.

Since then there’s been a reversal. Bitcoin is not only back over the 50% market share mark, it has effectively doubled its portion of crypto worth over the last two years.

What happened? Why altcoins have struggled isn’t something we can answer with a single data point or chart. But we can highlight a few reasons that help explain what happened. We’ll start with a look at the data and then we’ll highlight three ideas concerning what changed that pushed altcoins down, and bitcoin back up.

Over the past few weeks we’ve spent most of our time digging into IPOs, larger startups, stocks and revenue thresholds. Today we’re expanding our horizons a bit, looking at a market that sits somewhere to the side of our usual public-private divide. We’re having fun!

Let’s start with a few caveats to save tweets.

We all know that comparing the value of a cryptocurrency or token isn’t the only way to stack blockchains against one another. We also also know that comparing market caps isn’t a perfect way to examine the market. And, yes, there’s lots of development work that goes on behind the scenes that doesn’t show up in the data we are going to examine.

That said, we’re nearly 11 years into the bitcoin era. We care a bit more today than we did a half-decade ago about what is, versus what might be.

From the fine folks over at CoinMarketCap, the following set of data maps the relative value of the major cryptos, with smaller coins aggregated into a shared line:

I know it’s the day after a major holiday, so let’s help out. The big orange area is bitcoin. The 2017-2018 era is the period in which altcoins had their heyday. And since mid-2018 you can see bitcoin recapture most of its lost, relative prominence.

Bearing in mind that the value of bitcoin has traded as high as roughly $20,000 in late 2017, and is worth about $7,400 today, the chart does not merely show bitcoin recovering its former value. But it does show how over the last two years bitcoin’s share of the value of traded cryptos has doubled. Here are the key data points:

More simply, bitcoin’s share of the value of all cryptos held steady above 80% for a very long time. Then in early 2017 that same share began to fall. It continued to slip into the early days of 2018. Since then it recovered first to its December 2017 levels. And this year the relative value of bitcoin rose again, bringing it to twice its lowest ratings.

Why did that happen? Here are three reasons that form a part of the why.

For those of you with pie to eat, here’s our arguments upfront. Bitcoin bounced back due to:

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the gray space in between.

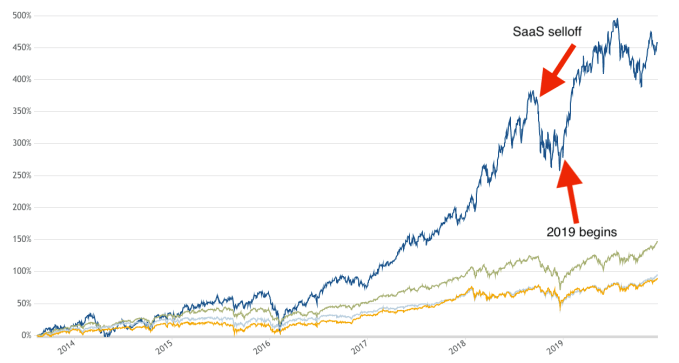

Today, something short. Continuing our loose collection of looks back of the past year, it’s worth remembering two related facts. First, that this time last year SaaS stocks were getting beat up. And, second, that in the ensuing year they’ve risen mightily.

If you are in a hurry, the gist of our point is that the recovery in value of SaaS stocks probably made a number of 2019 IPOs possible. And, given that SaaS shares have recovered well as a group, that the 2020 IPO season should be active as all heck, provided that things don’t change.

Let’s not forget how slack the public markets were a year ago for a startup category vital to venture capital returns.

We’re depending on Bessemer’s cloud index today, renamed the “BVP Nasdaq Emerging Cloud Index” when it was rebuilt in October. The Cloud Index is a collection of SaaS and cloud companies that are trackable as a unit, helping provide good data on the value of modern software and tooling concerns.

If the index rises, it’s generally good news for startups as it implies that investors are bidding up the value of SaaS companies as they grow; if the index falls, it implies that revenue multiples are contracting amongst the public comps of SaaS startups.*

Ultimately, startups want public companies that look like them (comps) to have sky-high revenue multiples (price/sales multiples, basically). That helps startups argue for a better valuation during their next round; or it helps them defend their current valuation as they grow.

Given that it’s Christmas Eve, I’m going to present you with a somewhat ugly chart. Today I can do no better. Please excuse the annotation fidelity as well:

Powered by WPeMatico

Mastercard announced today that it is acquiring RiskRecon, a Salt Lake City startup that uses publicly available data to build security assessments of organizations. The companies did not share the purchase price.

It has become increasingly important for financial services companies like Mastercard to help customers navigate cybersecurity, and RiskRecon will give customers an objective score of a company’s risk profile.

“Through a powerful combination of AI and data-driven advanced technology, RiskRecon offers an exciting opportunity to complement our existing strategy and technology to secure the cyber space,” Ajay Bhalla, president of cyber and intelligence for Mastercard, said in a statement.

RiskRecon CEO Kelly White told TechCrunch in a 2016 interview after the company’s $3 million seed round that the company looks at information that is readily available on the internet and puts it together to measure a company’s overall security risk:

RiskRecon leverages information that is available on the web from companies operating there as part of the act of doing business. “If you stand up web servers and DNS servers, these are intentionally discoverable because they are providing services on the internet. Systems reveal the software being run and version information from which you can determine security performance.”

White sees joining Mastercard as an opportunity to be a part of a larger organization and all that that entails. “By becoming part of their team, we have an opportunity to scale our solution and help companies in new industries and geographies take steps to better manage their cybersecurity risk,” he said in a statement.

RiskRecon launched in 2015 and has raised $40 million, according to Crunchbase data. Investors included Accel, Dell Technologies Capital, General Catalyst and F-Prime Capital.

It’s worth noting that the company was not alone in the space, competing with New York City-based SecurityScoreCard, which launched in 2013 and has raised over $112 million, according to Crunchbase. The last investment came in June for $50 million.

Today’s deal is subject to standard regulatory approval, but is expected to close in the first quarter in 2020.

Powered by WPeMatico

Now that the final technology IPOs of 2019 have touched down, it’s a good time to start looking back at what happened during the year. We’re hunting for trends as the clock winds down. Here’s one that’s obvious: Hardware startups are still struggling.

It’s cliché to note in startupland that hardware is hard. Everyone knows it. Making hardware is difficult by itself, but as all tech hardware requires software, hardware shops wind up needing wider domain expertise than pure-software startups. And that’s hard.

But even if a nuts-and-bolts tech company hits scale, it seems difficult to keep that momentum up.

This year we saw Peloton, a hybrid hardware and digital services company, go public and struggle. Despite a recent public market resurgence, the company is slipping back toward its IPO price. Today its equity is trading down about 6% to around $30 per share. The company’s IPO price of $29 is uncomfortably close to its current value.

2019’s IPO crop also included EHang, a late entry to the market (more here on its debut) that quickly began to lose altitude after it started to float. EHang traded up today, but the firm is still worth less than its IPO valuation, a reduced figure that was dinged during the China-based drone company’s march toward the public markets.

So, Peloton is about flat and EHang is down. That’s not a great mix of results for a year’s IPO class of hardware companies. Looking back in time, things don’t get much better.

NIO, a China-based electric car company (despite making this thing of beauty), has deleted about two-thirds of its value since its late-2018 U.S.-listed IPO. After going public at $6.25, shares of NIO are worth just $2.70 today.

Sonos also went public in the United States in 2018. It traded above its IPO price of $15 at first. Then it fell under $10 per share as 2018 came to a close. The smart speaker and stereo company spent 2019 recovering. It’s now worth its IPO price again, closing trading today worth about $14.80 per share.

If you go back to 2017, however, Roku has kicked ass. After pricing at $14 per share, the TV hardware and digital services firm is trading for $137 per share, a nearly 10x gain. But Roku was moving away from hardware at the time of its IPO, making it a somewhat poor example. Hardware revenues for Roku were just 31% of revenue in its most recent quarter, for example. That figure was 42% in the year-ago quarter. It will continue to fall.

We don’t need to go over what happened to Fitbit and GoPro, I don’t think.

Hardware can make a lot of money. Samsung and Apple make oceans of money from their hardware. Microsoft has managed to make Surface into a real business, with billions of dollars in yearly revenue. Amazon has a big hardware business with both consumer reading gadgets and consumer surveillance devices. Even Google is taking its new phone seriously enough to buy out a chunk of the NBA’s ad slots (I think it’s this one), according to my extensive in-market testing. Facebook is the laggard of the group.

But for smaller hardware companies going public, unless I’m missing a number of recent of IPOs — and I don’t think that I am — it’s a tough world out there.

Powered by WPeMatico

F5 got an expensive holiday present today, snagging startup Shape Security for approximately $1 billion.

What the networking company gets with a shiny red ribbon is a security product that helps stop automated attacks like credential stuffing. In an article earlier this year, Shape CTO Shuman Ghosemajumder explained what the company does:

We’re an enterprise-focused company that protects the majority of large U.S. banks, the majority of the largest airlines, similar kinds of profiles with major retailers, hotel chains, government agencies and so on. We specifically protect them against automated fraud and abuse on their consumer-facing applications — their websites and their mobile apps.

F5 president and CEO François Locoh-Donou sees a way to protect his customers in a comprehensive way. “With Shape, we will deliver end-to-end application protection, which means revenue generating, brand-anchoring applications are protected from the point at which they are created through to the point where consumers interact with them—from code to customer,” Locoh-Donou said in a statement.

As for Shape, CEO Derek Smith said that it wasn’t a huge coincidence that F5 was the buyer, given his company was seeing F5 consistently in its customers. Now they can work together as a single platform.

Shape launched in 2011 and raised $183 million, according to Crunchbase data. Investors included Kleiner Perkins, Tomorrow Partners, Norwest Venture Partners, Baseline Ventures and C5 Capital. In its most recent round in September, the company raised $51 million on a valuation of $1 billion.

F5 has been in a spending mood this year. It also acquired NGINX in March for $670 million. NGINX is the commercial company behind the open-source web server of the same name. It’s worth noting that prior to that, F5 had not made an acquisition since 2014.

It was a big year in security M&A. Consider that in June, four security companies sold in one three-day period. That included Insight Partners buying Recorded Future for $780 million and FireEye buying Verodin for $250 million. Palo Alto Networks bought two companies in the period: Twistlock for $400 million and PureSec for between $60 and $70 million.

This deal is expected to close in mid-2020, and is of course, subject to standard regulatory approval. Upon closing Shape’s Smith will join the F5 management team and Shape employees will be folded into F5. The company will remain in its Santa Clara headquarters.

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to Equity, TechCrunch’s venture capital-focused podcast, where we unpack the numbers behind the headlines.

This week Kate was in SF, Alex was in Providence and there was a mountain of news to shovel through. If you’re here because we mentioned linking to a certain story in the show notes, that’s here. For everyone else, let’s get into the agenda.

We kicked off with a look at three new venture funds. In order:

From there we turned to the gender imbalance in the world of venture capital. This year, companies founded by women raised only 2.8% of capital. These not-so-stellar statistics are always worth digging into.

We then took a quick look at two different venture rounds, including ProdPerfect’s $13 million Series A and Pepper’s smaller $5.6 million round. ProdPerfect’s round was led by Anthos Capital (known for investing in Honey, which sold for $4 billion). The company has $2 million in ARR and is growing quickly. Pepper, formed by former Snap denizens, is working to help other startups lower their CAC costs in-channel. Smart.

And finally, Alex wanted to bring up his series on startups that reach the $100 million ARR threshold (Extra Crunch membership required). A first piece looking into the idea led to a few more submissions. There seem to be enough companies to name the grouping with something nice. Centurion? Centipede? Centaur? We’re working on it.

Equity drops every Friday at 6:00 am PT, so subscribe to us on Apple Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify and all the casts.

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the grey space in between.

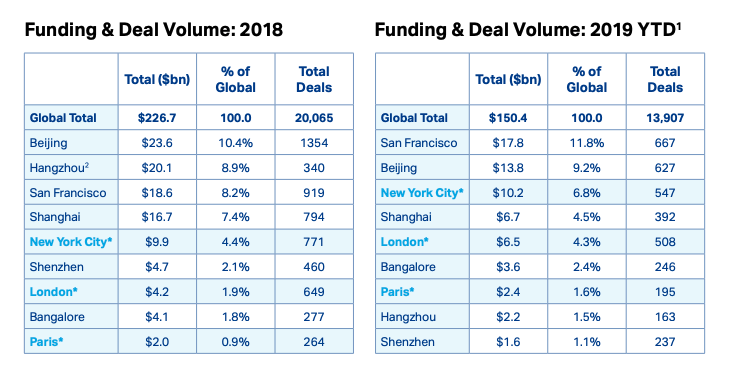

Today, we’re digging into a host of data concerning the East Coast venture capital scene, specifically looking into the performance of its two key startup markets.

It’s 12 degrees Fahrenheit as I write this in my office situated between Boston and New York City — a perfect vantage point for studying these vibrant tech ecosystems. Let’s see what the data tells us.

The information we’re examining today comes from White Star Capital (often via CBInsights), a venture capital firm that describes itself as “transatlantic” and takes part in seed, Series A and Series B rounds around the globe. The group last raised a $180 million fund that TechCrunch covered here, noting at the time that capital pool was “oversubscribed from an initial target of $140 million” and would be invested into “around 20 new companies from the new fund, writing opening cheques of between $1 million and $6 million.”

With boots on the ground in New York, White Star cares about the East Coast, so the fund’s put dossier on the region isn’t unexpected. What it includes, however, is.

We’ll start with NYC and its surprising 2019 before turning to Boston, digging into its super-giant venture totals and hearing from Founder Collective’s Eric Paley on the state of things in urban Massachusetts.

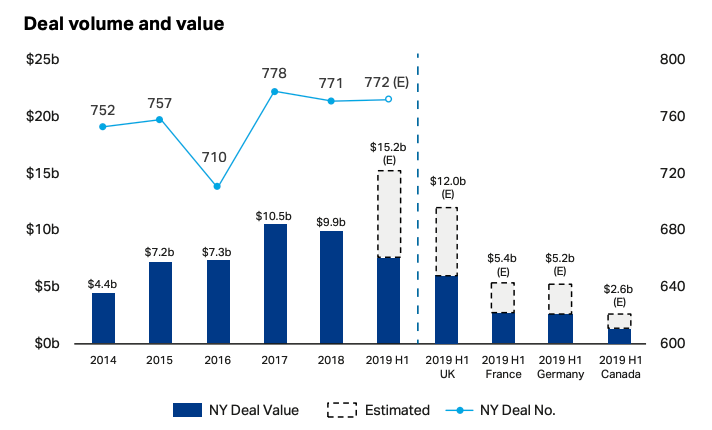

White Star’s report details record-breaking figures for NYC’s current year. Off of effectively flat deal volume (New York City sees around 775 venture deals per year at the moment, or a little more than two per day), the overgrown town should set record venture dollar volume in 2019.

Observe the following, astounding chart detailing the abnormality of 2019 from a comparative venture dollar perspective:

By smashing 2017’s local maximum, 2019 appears set to crush the city’s record — and rich — venture investment totals. The graphic also manages to point out (somewhat embarrassingly) that Gotham will manage to best a number of European countries’ aggregate venture dollar investments by itself this year.

That’s is a useful bit of context as in the United States, New York City is always Number Two to Silicon Valley. But, this chart argues, being number two in the number-one market is still a hell of a lot of capital.

Putting New York City’s venture into even sharper comparative perspective, observe the following table:

Powered by WPeMatico

Leapfin, a startup selling corporate finance tooling, announced a $4.5 million round this morning. The funding event was led by Bowery Capital, and included dollars from a number of former technology executives.

Before its newly announced investment, the company had raised just a small seed round. The small capital amounts may seem inconsequential, but they’re more strategic than anything. According to Leapfin CEO Raymond Lau, the company is running lean and keeping an eye on profitability.

After being founded in 2015 and starting commercialization of its product in 2018, the company is stepping a bit further out of the shadows this morning. Let’s talk about what it does, and why both its product and business philosophy are neat.

Leapfin helps companies track their revenue and cost of revenue expenses.

In more human terms, Leapfin helps companies track sales, and how much it costs to create and distribute its goods and services to customers. “Cost of revenue,” also known (roughly) as “cost of goods sold,” may sound like a jargony accounting term, but in reality it’s a bedrock business concept that anyone involved with startups needs to understand.

Let’s explain why. Once you deduct costs of revenue from revenue itself, you’re left with gross profit. That’s what businesses use to cover their operating costs. And, crucially, the larger a company’s gross profit is in relation to its revenue, the higher margin its revenue is; investors love high gross margin revenue.

In part, their high gross margins are why software startups are worth so much.

Back to Leapfin, its product is a shot at making business a more limpid process. In a call with TechCrunch, Leapfin’s Lau explained that many companies only have “one-in-thirty” visibility into their operations; that business owners only manage to fully collate their revenue and cost of revenue results monthly, meaning that the rest of the time they are flying at least partially blind.

The goal of Leapfin, according to Lau, is to provide a “single source of truth” for ongoing business results, using “robotic process automation” to help companies cut down on repetitive work. So Lepafin does two things: helps companies know where they stand financially, and saves them time on rote tasks that tend to come with accounting.

The company is pretty happy with its ability to sell its product so far. Lau told TechCrunch that it has found “very, very strong product market fit,” for example. Asked to describe when he felt that Leapfin had gelled with the market, Lau explained that in his view, product market fit is more “process” than a “tipping point,” but that he was confident in Leapfin’s product-market harmony when its customers began referring other companies (to a product that costs six-figures annually), and its sales cycle tightened.

Leapfin is run a bit differently from most SaaS companies that we cover. Instead of raising lots to invest in blow-out sales and marketing expenses, Leapfin is running pretty lean.

TechCrunch asked Lau why he only raised $4.5 million in the new round, which, given the product progress his company has made, felt modest. He said that the Leapfin staff “are outsiders in a way,” and that while his “peers are raising tens of millions,” his company could be profitable by the third quarter of next year. So Leapfin doesn’t need more money, and selling shares ahead of growth is an expensive way to raise capital.

Lau also said, however, that his company’s small raise “doesn’t mean that [it] won’t raise more down the road.” Another check in 2020 to ward off any downturn fears would make some sense. But Leapfin probably won’t sweat a crash too much, as the company keeps profitability and cash flow positivity “in sight,” according to its CEO.

Despite that, the company expects to hire quickly, expanding from around 20 people today to 50 by the end of next year. What we need next from Leapfin is an ARR number so we can vet just how much product market fit it really has.

Powered by WPeMatico

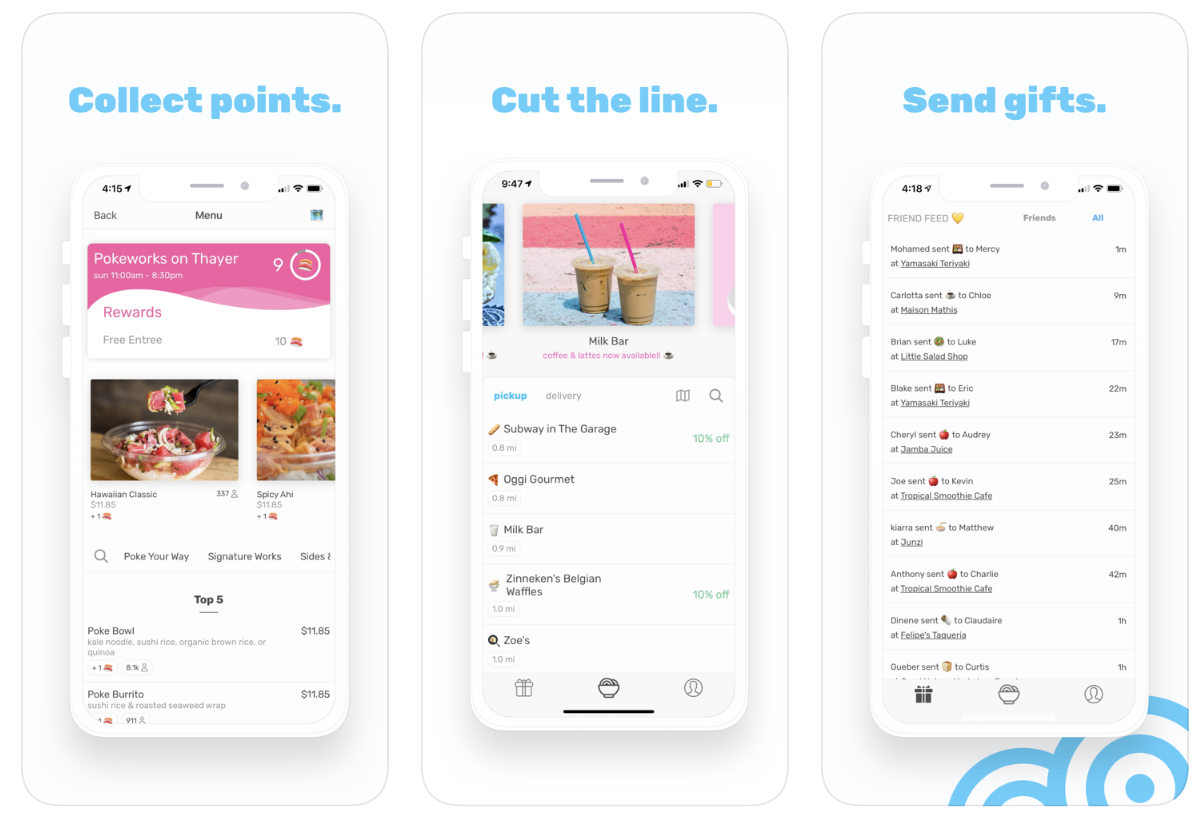

“We were in the back washing blenders so they could keep taking Snackpass orders,” recalls co-founder and CEO Kevin Tan. The team from order-ahead food startup Snackpass was willing to get their hands dirty to keep up with demand at one of their first restaurant partners, Tropical Smoothie Cafe on the Yale University campus.

Why were people so eager to pay for takeout through Snackpass? Because it lets them earn loyalty points to redeem for free food — both for themselves and as gifts for their friends. Sending people Snackpass rewards became a new way to flirt or show gratitude at Yale. And through the Venmo-esque Snackpass social feed, users could keep up with a fresh form of gossip while discovering restaurants.

“Anywhere someone is standing in line to order something, we can solve that with Snackpass,” says Tan. “Consumer spending will be social in the future.”

That future is already taking hold. Two years after launch, Snackpass is on 11 college campuses across the U.S., often boasting a 75% penetration rate amongst students within six months. It takes a cut of every order and keeps margins high because users pick up the food themselves rather than waiting for delivery. While other food ordering startups battle to offer discounts as marauding users deal-hop between apps, Snackpass keeps users coming back through its loyalty program.

Its momentum, retention and opportunity to expand from colleges to dense cities has now won Snackpass a $21 million Series A led by Andreessen Horowitz partner Andrew Chen. The round was joined by other heavy hitters, like Y Combinator, General Catalyst, Inspired Capital and First Round, plus angels, including musician Nas, NFL star Larry Fitzgerald and legendary talent agent Michael Ovitz. Building on Snackpass’ $2.7 million seed, the cash will go toward hiring up with the goal of reaching 100 campuses in two years.

Its momentum, retention and opportunity to expand from colleges to dense cities has now won Snackpass a $21 million Series A led by Andreessen Horowitz partner Andrew Chen. The round was joined by other heavy hitters, like Y Combinator, General Catalyst, Inspired Capital and First Round, plus angels, including musician Nas, NFL star Larry Fitzgerald and legendary talent agent Michael Ovitz. Building on Snackpass’ $2.7 million seed, the cash will go toward hiring up with the goal of reaching 100 campuses in two years.

“Takeout is an important market because it’s huge — also in the hundreds of billions — and fragmented,” writes Chen. “The opportunity complements the food delivery market in a big way: For the average restaurant, there are 6 takeout orders for every delivery order!”

Like many of the best startup ideas, Snackpass was born out of the founders’ own needs at Yale. Slow and expensive food delivery services didn’t make sense for smaller orders like a coffee, ice cream or a pepperoni slice on campuses small enough for customers to walk or bike to the restaurant. Tan says, “I was dabbling in several side projects, including helping a friend who managed a local pizza shop build a website to help better reach the local student community.” He realized how tough it was for restaurants around colleges to retain and reward customers, especially as regulars graduated.

Tan joined up with neuroscience student and Thiel Fellow Jamie Marshall, who became Snackpass’ COO. “I had grown up calling in every order,” Marshall tells me. “Waiting in line didn’t make sense for me. I used every order-ahead platform and thought this was the future.” Jonathan Cameron, a serial entrepreneur who’d built his own order-ahead app called Happy Hour, rounded out the founding team.

Snackpass founders (from left): Jamie Marshall and Kevin Tan

Snackpass offers users a list of nearby restaurants from which they can order ahead, with special tags for ones offering deals. Menu items include counts of how many people have ordered them and how many rewards points you’ll earn buying them. You pay in the app, skip the line at the restaurant and grab your order from the counter. Each restaurant can configure their own rewards system with how much items earn and cost, such as giving you a free coffee for every 10 you buy.

Users can then spend their points to get themselves free menu items, or send a virtual Snackpass gift card to any of their phone contacts or people they find via search. This gives Snackpass a way to grow virally that most food apps lack. Thankfully, you can block people on Snackpass if they get creepy showering you with gifts.

Each purchase and gift on Snackpass shows up in its social feed unless you make it private. “That’s become its own language. People use it to flirt with each other, or bond and connect with someone new,” Tan tells me. “There’s some drama or intrigue there seeing who’s sending gifts to who. People even look at the feed in the way they look at someone’s Instagram to see what’s going on with them.”

Snackpass has also done some integration work specifically for the college market that sets it apart from other order-ahead and delivery services. It can sync with students’ campus meal plans so they can spend them through the app. And student groups from clubs to fraternities can pre-load and replenish accounts for their members. Snackpass works with the same organizations to launch on new campuses. “We host parties, sponsor tailgates and make it feel like a student-led effort so it grows organically across campus communities,” Tan explains. “These efforts, combined with the social feed which would give anyone FOMO if they’re not in the app.”

With all the competition in the space, restaurants can be inundated with apps to manage, some of which just exacerbate spikes in demand that overwhelm kitchens. “There is certainly a risk that local restaurants will start to get platform fatigue, finding that using some apps will take too big of a bite out of their margins,” says Tan. That’s why Snackpass built features that let restaurants batch orders and control how many come in at a certain time so dine-in patients and non-app users aren’t stuck with unreasonable delays.

With all the competition in the space, restaurants can be inundated with apps to manage, some of which just exacerbate spikes in demand that overwhelm kitchens. “There is certainly a risk that local restaurants will start to get platform fatigue, finding that using some apps will take too big of a bite out of their margins,” says Tan. That’s why Snackpass built features that let restaurants batch orders and control how many come in at a certain time so dine-in patients and non-app users aren’t stuck with unreasonable delays.

Snackpass has recruited talent from Uber Eats and an advisor from Yelp’s executive team to help it navigate the tricky SMB sales process. One ace up its sleeve is that it can offer to send push notifications to announce recently signed partners or specials they’re launching, driving the new customers restaurants are desperate for. Tan says his startup is considering if it could charge for this kind of promotion down the line. Most customers who walk into restaurants are effectively in incognito mode, but Snackpass provides its partners with analytics to help them improve their own businesses.

“At the surface level there is a lot of competition in this space,” Tan admits. “The social aspect of the app has been the key differentiator for us. Other companies have been focused on creating the fastest, cheapest, most efficient delivery service, but it’s really hard to make those margins work and consumers are trained to shop around on different apps to get the best deal or fastest delivery time . . . Eating food is supposed to be fun and social, and our generation grew up online and in social networks. We’re combining the social aspect of eating with the utility of order ahead, which has helped us build loyalty and enable retention amongst our users.”

It will still be a battle to overtake long-running competitors like Allset, Level Up and Ritual, plus incumbents that offer takeout pickup like Uber and Grubhub. Logistics is a cut-throat business, and plenty of startups have already failed in the restaurant loyalty space.

Having Andreessen Horowitz’s support could give Snackpass some extra firepower. “A16z has better support and services for their portfolio companies than any other VC we’ve come across and they’ve delivered,” Tan tells me. “We knew that Andrew Chen understands growth and marketplaces from his blog and his Twitter.” That’s critical in a crowded space where such a precise balance of customer acquisition and lifetime value is necessary.

Snapchat, TikTok and Fortnite have all tapped into the youth market with a lighthearted nature that keeps users coming back until they develop network effect. Snackpass is managing to do the same, not with a messaging app or game, but a commerce platform. “We play up creativity, silliness and delight in areas where most companies focus on utility and convenience,” Tan concludes. “We built Snackpass for ourselves and our friends. We’ve carried on this philosophy: if something makes us laugh, we put it in the app.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the grey space in between.

Today we’re exploring the 2019 IPO cohort from a capital-in perspective. How much did tech companies going public in 2019 raise before they went public, and what impact that did that have on their valuation when they debuted?

Looking ahead, the tech startups and other venture-backed companies expected to go public in 2020 will include a similar mix of mid-sized offerings, unicorn debuts and perhaps a huge direct listing. What we’ve seen in 2019 should be a good prelude to the 2020 IPO market.

With that in mind, let’s examine how much money tech companies that went public this year raised before their IPO. Spoiler: It’s a lot more than was normal just a few years ago. Afterwards, I have a question regarding what to call companies in the $100 million ARR club (more here) that we’ve been exploring lately. Let’s go!

According to CBInsights’ recent IPO 2020 IPO report, there’s a sharp, upward swing in the amount of capital that tech companies raise before they go public. It’s so steep that the data draw a nearly linear breakout from a preceding, comfortable normal.

Here’s the chart:

There are two distinct periods; from 2012 to 2015, raising up to $100 million was the norm (median) for tech companies going public. That’s still a lot of cash, mind.

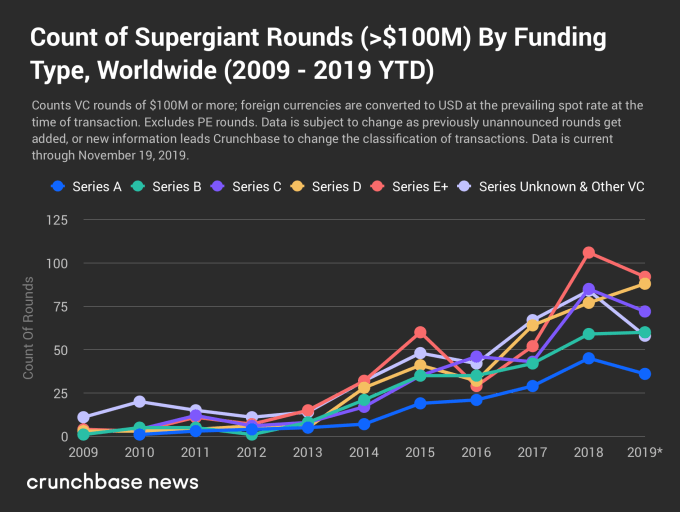

The second period is more exciting. From 2016 on we can see a private capital arms race in which tech companies going public stacked ever-greater sums under their mattresses before debuting. This is generally consistent with a different trend that you are also aware of, namely the rise of $100 million financings.

Before we turn back to the CBInsights data, let’s observe a chart from Crunchbase News that underscores the simply astounding rise of $100 million financings that was published just a few weeks ago. As you look at this chart, remember that prior to 2016, more than half of venture-backed technology companies going public had raised less than $100 million total:

Now, compare the two data sets.

Powered by WPeMatico