Fundings & Exits

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Spotify did it. Slack did it. Many other late-stage private technology companies are reported to be seriously considering it. Should yours?

If you are a board member of a late-stage, venture-backed company or part of its management team, you likely have heard of the term “direct listing.” Or you may have attended one or all of the slew of recent conferences being hosted by big-name investment banks and others, including tech investor guru Bill Gurley, who recently debated the pros and cons of choosing a direct listing over a traditional IPO.

Before you decide what’s right for your company, here are a few things you need to know about direct listings.

For people not familiar with the term, a direct listing is an alternative way for a private company to “go public,” but without selling its shares directly to the public and without the traditional underwriting assistance of investment bankers.

In a traditional IPO, a company raises money and creates a public market for its shares by selling newly created stock to investors. In some instances, a select number of pre-IPO investors, usually very large stockholders or management, may also sell a portion of their holdings in the IPO. In an IPO, the company engages investment bankers to help promote, price and sell the stock to investors. The investment bankers are paid a commission for their work that is based on the size of the IPO—usually seven percent for a traditional technology company IPO.

In a direct listing, a company does not sell stock directly to investors and does not receive any new capital. Instead, it facilitates the re-sale of shares held by company insiders such as employees, executives and pre-IPO investors. Investors in a direct listing buy shares directly from these company insiders.

Does this mean that a company doing a direct listing doesn’t need investment banks? Not quite. Companies still engage investment banks to assist with a direct listing and those banks still get paid quite well (to the tune of $35 million in Spotify and $22 million in Slack).

However, the investment banks play a very different role in a direct listing. Unlike a traditional IPO, in a direct listing, investment banks are prohibited under current law from organizing or attending investor meetings and they do not sell stock to investors. Instead, they act purely in an advisory capacity helping a company to position its story to investors, draft its IPO disclosures, educate a company’s insiders on process and strategize on investor outreach and liquidity.

The concept of a direct listing is actually not a new one. Companies in a variety of industries have used similar structures for years. However, the structure has only recently received a lot of investor and media attention because high-profile technology companies have started to use it to go public. But why have technology companies only recently started to consider direct listings?

The rise of massive pre-IPO fundraising rounds

With an abundance of investor capital, especially from institutional investors that historically hadn’t invested in private technology companies, massive pre-IPO fundraising rounds have become the norm. Slack raised over $400 million in August 2018—just over a year prior to its direct listing. Because of this widespread availability of capital, some technology companies are now able to raise sufficient capital before their actual IPO to either become profitable or put them on a path to profitability.

Criticism of current IPO process

There has been increasing negative sentiment, especially amongst well-known venture capitalists, about certain aspects of the traditional IPO process—namely IPO lock-up agreements and the pricing and allocation process.

IPO lock-up agreements. In a traditional IPO, investment bankers require pre-IPO investors, employees and the company to sign a “lock-up agreement” restricting them from selling or distributing shares for a specified period of time following the IPO—usually 180 days. The bankers put these agreements in place in order to stabilize the stock immediately after the IPO. While the merits of a lock-up agreement can certainly be debated, by the time VCs (and other insiders) are allowed to sell following an IPO, oftentimes the stock price has fallen significantly from its highs (sometimes to below the IPO price) or the post lock-up flood of selling can have an immediate negative impact on the trading price.

In a direct listing, there is no lock-up agreement, which allows for equal access to the offering to all of the company’s pre-IPO investors, including rank-and-file employees and smaller pre-IPO stockholders.

IPO pricing and allocation: In a traditional IPO, shares are often allocated directly by a company (with the assistance of its underwriters) to a small number of large, institutional investors. Traditional IPOs are often underpriced by design to provide large institutional investors the benefit of an immediate 10-15% “pop” in the stock price. Over the last few years, some of these “pops” have become more pronounced. For example, Beyond Meat’s stock soared from $25 to $73 on its first day of trading, a 163% gain. This has fueled a concern, particularly shared amongst the VC community, that investment banks improperly price and allocate shares in an IPO in order to benefit these institutional investors, which are also clients of the same investment banks that are underwriting the IPO. While the merits of this concern can also be debated, in instances where there is a large price discrepancy between the trading price of the stock following the IPO and the price of the IPO, there is often a sense that companies have left money on the table and that pre-IPO investors have suffered unnecessary dilution. If the IPO had been priced “correctly,” the company would have had to sell fewer shares to raise the same amount of proceeds.

Because a company is not selling stock in a direct listing, the trading price after listing is purely market driven and is not “set” by the company and its investment bankers. Moreover, since no new shares are issued in a direct listing, insiders do not suffer any dilution.

The Spotify effect

Before Spotify’s direct listing, technology companies hadn’t used the direct listing structure to go public. Spotify was, in many ways, the perfect test case for a direct listing. It was well known, didn’t need any additional capital and was cash flow positive. In addition, prior to its direct listing, Spotify had entered into a debt instrument that penalized the company so long as it remained private. As a result, it just needed to go public. After clearing some regulatory hurdles, Spotify successfully executed its direct listing in April 2018. After Spotify’s direct listing, Slack (relatively) quickly followed suit. Slack’s direct listing was notable because it represented the first traditional Silicon Valley-based VC-backed company to use the structure. It was also an enterprise software company, albeit one with a consumer cult following.

While a direct listing offers many benefits, the structure does not make sense for every company. Below is a list of key benefits and drawbacks:

Powered by WPeMatico

In the wake of WeWork’s embarrassing IPO rout, you might imagine that startups working in similar markets would cool it for a bit. Perhaps they could work on cutting spending, improving their gross margins, and, say, shooting for profitability.

Not so, at least in one case. Instead of doing those things, China-based Ucommune filed to go public in America this month. The WeWork competitor is mostly a co-working business. It’s also a marketing company. And it has some of the worst economics we’ve seen in a company since WeWork.

Why this company is trying to go public isn’t hard to understand. It needs the cash. But at the same time, the chance of it debuting at a price it likes seems slim, given the market’s recent history — as well as Ucommune’s own.

Before we chat about the business fundamentals of Ucommune, a primer on the company itself.

Founded in 2015, according to Crunchbase data, Ucommune has raised over hundreds of millions. In 2018 alone the company raised a venture round and its Series C and its Series D. Prior investors include Gopher Asset Management, Aikang Group, Tianhong Asset Management, All-Stars Investment and Longxi Real Estate.

TechCrunch reported that its final private round valued Ucommune at $3 billion.

All that capital was put to work. According to is F-1 filing, Ucommune operates 197 co-working facilities in 42 cities. The company also claims more than 600,000 members and nearly 73,000 workstations.

The WeWork similarities continue: While discussing itself in its IPO filing, the firm touts an “asset-light model,” which it claims helps property owners “benefit from our professional capabilities and strong brand recognition” as well as allowing its “business to scale at a cost-efficient manner.”

Let’s see.

As a primer for all you non-accountants, here’s how you make money as a company: First, generate some revenue. Next, deduct the direct costs that that revenue engendered. What’s left is called “gross profit,” and the relative total of gross profit generated from revenue is called gross margin. From there, subtract your operating costs. If there’s anything left over, that’s operating profit. Now take your operating profit and remove taxes and other costs. What remains is net income.

As you can quickly see, the more gross profit a business generates from its revenue, the more money is has left over to pay for operating expenses. So, revenues that generate lots of gross profit — called high-margin revenue — are better than those that don’t.

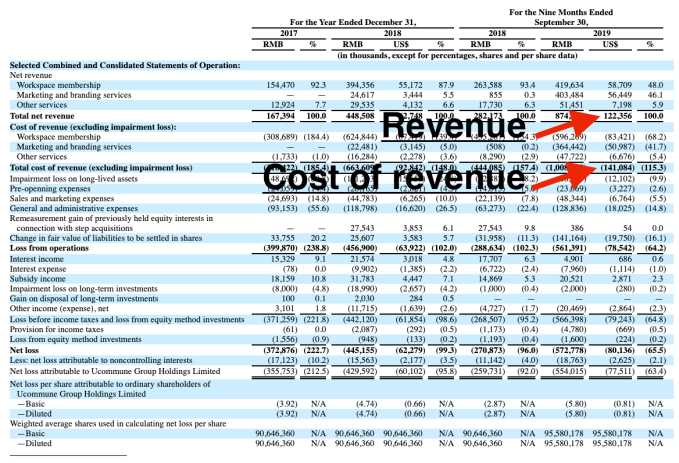

Ucommune, our IPO hopeful, is unique in that its revenue doesn’t generate any gross profit at all. Its revenue doesn’t even pay for itself. The company is gross margin negative.

Here’s what that looks like:

If your cost of revenue is higher than your revenue, your gross profit is negative. And that means that you have no gross margin available to fund operating costs. In turn, that means that your company is super unprofitable.

Ucommune is unprofitable, unsurprisingly. (If it feels like we’re overly focused on gross margins, keep in mind that software companies are worth as much as they are in part because they have very high gross margins.)

Things get a bit worse when we look further.

Digging in, Ucommune operates two main businesses. The first enterprise is co-working, which generated just less than half of the company’s total revenue during the first three quarters of 2019. Its second largest business is a marketing effort. Ucommune acquired a company called “Shengguang Zhongshuo” in December of 2018, a deal that lets the company drive revenue by selling “branding services and online targeted marketing services.”

Ucommune is therefore a hybrid co-working and services business. Neither piece of the whole is attractive from a margin perspective. For example, the company’s $58.7 million in co-working revenue earned during the first nine months of 2019 was nearly entirely offset by lease costs ($49.6 million) alone, before the company staffed and otherwise managed the locations in question.

The company’s marketing business is slightly better. Its $56.5 million in revenue from the first three quarters of 2019 was nearly offset by $51.0 million in revenue costs. Ucommune’s services arm, therefore, was more lucrative in terms of generating gross margin for the co-working company than its actual co-working business.

(Bear in mind as we go along that this company wants to go public.)

Wrapping our discussion of yuck, let’s talk about cash. Ucommune had cash and equivalents of $23.4 million and short-term investments worth $11.0 million at the end of Q3 2019. That’s $33.4 million in total that the company can access, presuming that every short-term investment is unwindable into cash inside the window in which Ucommune would need to access it.

A window that is closing, mind. Ucommune’s operations burned through $32.4 million in the first three quarters of 2019. If the company kept consuming cash at its prior pace, we can estimate that it will not have enough cash to make it to the end of Q2 2020. Which is why Ucommune is going public.

The only counterargument to the mess that is Ucommune’s business is that it is growing quickly. That’s true. The company’s revenue grew from ¥282.2 million in the first three quarters of 2018 to ¥874.6 million over the same time period this year. That’s quick!

But instead of demonstrating operating leverage (losing less money as its revenue grew), the company lost more money this year than the last, making its business appear likely to keep burning acres of cash while it grows. And you have to ask yourself if it is a good business, why are its private investors pushing it onto the public markets instead of giving it more of their own money?

They must have known, landing this close to WeWork, how this was going to look. And that’s not confidence-inspiring.

Powered by WPeMatico

Hugging Face has raised a $15 million funding round led by Lux Capital. The company first built a mobile app that let you chat with an artificial BFF, a sort of chatbot for bored teenagers. More recently, the startup released an open-source library for natural language processing applications. And that library has been massively successful.

A.Capital, Betaworks, Richard Socher, Greg Brockman, Kevin Durant and others are also participating in today’s funding round.

Hugging Face launched its original chatbot app back in early 2017. After months of work, the startup wanted to prove that chatbots don’t have to be a glorified command line interface for customer support.

With the app, you could generate a digital friend and text back and forth with your companion. And it wasn’t just about understanding what you meant — the app tried to detect your emotions to adapt answers based on your feelings.

It turns out that the technology behind that chatbot app is solid. As Brandon Reeves from Lux Capital wrote, there’s been a ton of progress when it comes to computer vision and image processing, but natural language processing has been lagging behind.

Hugging Face’s open-source framework Transformers has been downloaded over a million times. The GitHub project has amassed 19,000 stars, proving that the open-source community thinks this is a useful brick to build upon. Researchers at Google, Microsoft and Facebook have been playing around with it.

Some companies even use it in production, such as challenger bank Monzo for its customer support chatbot and Microsoft Bing. You can leverage Transformers for text classification, information extraction, summarization, text generation and conversational artificial intelligence.

With today’s funding round, the company plans to triple its headcount in New York and Paris.

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the grey space in between.

Today we’re looking into Uber’s bike bet and what the push could mean for Lime and other micromobility companies working to find a sustainable business model. As profitability comes back into vogue among investors at the expense of growth, both Uber and a cadre of mobility-focused startups are hoping that electric- and pedal-powered transport pay off.

Let’s take a look.

Uber is most famous for its ride-hailing business, and the on-demand car-hire service that Uber was founded upon still generates the bulk of its revenue. In its most recent quarter, for example, Uber’s ride-hailing segment generated $2.86 billion in adjusted net revenue. The next-largest Uber business, its Uber Eats segment, generated a comparatively modest $392 million in adjusted net revenue.

Which brings us to the smaller Uber efforts. Freight, its aptly-named hauling business, brought in $218 million in adjusted net revenue in the same quarter (Q3 2019). And finally, Uber’s “Other Bets” segment was responsible for $38 million in adjusted net revenue. That was the smallest result, but also the fastest-growing, exploding from $3 million in adjusted net revenue in the year-ago quarter.

While Q3 2019 was better for Uber than its preceding periods regarding growth, the company’s slowing expansion and stiff losses (its net loss in the period came to $1.16 billion), have left the global transportation giant hunting for new revenue. And its Other Bets segment, which includes incomes from “dockless e-bikes and e-scooters,” is growing like heck.

This recent news item was therefore not surprising:

“We want to double down on micromobility,” Christian Freese, Jump’s head of EMEA, told CNBC in an interview. “We have seen how beautifully it works with our core business and ride sharing, and want to invest more and deeper, especially in Europe.”

Uber claims adoption of Jump’s bikes and scooters in Europe has outpaced that of the U.S. in the last eight months. It says more than 500,000 Europeans rode the vehicles in the last eight months alone, racking up 5 million trips in total.

The move by Uber makes good sense. The firm needs to grow, it has found a vein of consumer interest to mine, and it has the scale (financial, and in terms of an existing userbase) to pull off the scheme.

Of course, even if Uber quadrupled its Other Bets income (which includes more than just micromobility dollars), the segment would only add up to around 4% of its Rides adjusted net revenue (using the company’s Q3 figure for reference.) Growth, however, is growth, and investors love a story.

Uber is not the only company that wants to make bikes and scooters work at scale. There are a number of startups around the world that have raised rafts of capital to do just that. And they don’t want Uber to win.

Powered by WPeMatico

Belgium-based all-in-one business software maker Odoo, which offers an open source version as well as subscription-based enterprise software and SaaS, has taken in $90 million led by a new investor: Global growth equity investor Summit Partners.

The funds have been raised via a secondary share sale. Odoo’s executive management team and existing investor SRIW and its affiliate Noshaq also participated in the share sale by buying stock — with VC firms Sofinnova and XAnge selling part of their shares to Summit Partners and others.

“Odoo is largely profitable and grows at 60% per year with an 83% gross margin product; so, we don’t need to raise money,” a spokeswoman told us. “Our bottleneck is not the cash but the recruitment of new developers, and the development of the partner network.

“What’s unusual in the deal is that existing managers, instead of cashing out, purchased part of the shares using a loan with banks.”

The 2005-founded company — which used to go by the name of OpenERP before transitioning to its current open core model in 2015 — last took in a $10M Series B back in 2014, per Crunchbase.

Odoo offers some 30 applications via its Enterprise platform — including ERP, accounting, stock, manufacturing, CRM, project management, marketing, human resources, website, eCommerce and point-of-sale apps — while a community of ~20,000 active members has contributed 16,000+ apps to the open source version of its software, addressing a broader swathe of business needs.

It focuses on the SME business apps segment, competing with the likes of Oracle, SAP and Zoho, to name a few. Odoo says it has in excess of 4.5 million users worldwide at this point, and touts revenue growth “consistently above 50% over the last ten years”.

Summit Partners told us funds from the secondary sale will be used to accelerate product development — and for continued global expansion.

“In our experience, traditional ERP is expensive and frequently fails to adapt to the unique needs of dynamic businesses. With its flexible suite of applications and a relentless focus on product, we believe Odoo is ideally positioned to capture this large and compelling market opportunity,” said Antony Clavel, a Summit Partners principal who has joined the Odoo board, in a supporting statement.

Odoo’s spokeswoman added that part of the expansion plan includes opening an office in Mexico in January, and another in Antwerpen, Belgium, in Q3.

This report was updated with additional comment

Powered by WPeMatico

This morning ProdPerfect, a technology startup focused on web application testing, announced a $13 million Series A led by Anthos Capital. Anthos is perhaps best known for investing in Honey, a startup which recently sold to PayPal for several billion dollars.

ProdPerfect, a remote-focused company, closed a $2.6 million seed round earlier in 2019. Fika Ventures and Eniac Ventures took part in the Series A after also putting capital into the company in the company’s preceding seed investment. The startup has now raised $15.7 million across three rounds, according to Crunchbase.

What does ProdPerfect’s product do regarding testing? And what is it going to do with all its new money? TechCrunch chatted with Dan Widing, ProdPerfect’s founder and CEO, to answer those questions, and learn how quickly the company is growing.

ProdPerfect automates end-to-end testing for web developers. According to Widing, the product “followed some of the lessons of the product analytics industry to build a tool that lets us quantitatively understand how our customers’ live users traverse the customers’ web application.” The company estimates that “many companies are compelled to put around 20% of their engineering budget into staffing a QA engineering department,” spend that it reckons it can help cut.

The web is a big place, with lots of pages and apps and more built and maintained by a global army of developers. Those end products require testing to find errors and bugs that could cause havoc for end users and companies alike. You can test well, or poorly. But according to Widing, the “gold standard of web testing is either directly or indirectly controlling a browser to traverse the site like a user does,” also known as “end-to-end testing.”

The product seems to have found early market traction. According to Widing, 18 months after landing its first handful of customers, his company has reached the 50-customer mark, generating “around $2 million” in annual recurring revenue (ARR), a standard revenue metric for modern software (SaaS) companies.

When TechCrunch last covered ProdPerfect, we called it a “Boston-based startup focused on automating QA testing for web apps.” All of that is still true aside from the location. According to its CEO, ProdPerfect transferred its headquarters from Boston to San Francisco earlier in 2019. However, Widing said, ProdPerfect doesn’t focus on the move much, as it views itself as “a remote-first company.”

But no matter where its nexus sits, the company plans on investing heavily in sales and marketing spend (traditional for a Series A-level company looking to quickly expand revenue), and invest in “product development and customer service,” according to Widing. So, tech investments, go-to-market spend and a modest war chest for the future are the game plan for ProdPerfect’s new money. (Widing noted in an email to TechCrunch that “it helps to have a good stockpile” in times of global macro uncertainty, which is a smart perspective.)

The firm ARR figure that ProdPerfect provided will help the market vet its progress over the next few years. The company will probably aim for more than a doubling in size next year, more likely shooting for a tripling. So, how close to $6 million ARR that ProdPerfect can reach in 2020 will be fun to watch. If the firm manages that sort of growth, expect it to raise again to keep investing in its product and go-to-market motion.

Photo by Ilya Pavlov on Unsplash

Powered by WPeMatico

HackerRank, a popular platform for practicing and hosting online coding interviews, today announced that it has acquired Mimir, a cloud-based service that provides tools for teaching computer science courses. Mimir, which is HackerRank’s first acquisition, is currently in use by a number of universities, including UCLA, Purdue, Oregon State and Michigan State, as well as by corporations like Google.

HackerRank says it will continue to support Mimir’s classroom product as a standalone product for the time being. By Q2 2020, the two companies expect to have an initial release of a combined product offering.

“HackerRank will work closely with professors, students and customers to help student developers learn, improve and assess their skills from coursework to career,” Vivek Ravisankar, the co-founder and CEO of HackerRank, told me. “Ultimately, we envision a combined product that allows students to obtain both a formal academic education as well as practical skills assessments which can help build a strong and successful career.”

The two companies did not disclose the financial details of the acquisition, but Indiana-based Mimir previously raised a total of $2.5 million and had eight employees at the time of the acquisition, including the three-person executive team.

As the companies stress, both focus on allowing developers for a variety of backgrounds to successfully vie for jobs, no matter where they went to school. HackerRank argues that the combination of its existing services and Mimir’s classroom tools will “provide computer science classrooms with the most comprehensive developer assessment platform on the market; allowing students to better prepare for real-world programming and universities to more accurately evaluate student progress.” The idea here clearly is to expand HackerRank’s reach into the world of academia and expand the talent pool for its customers who are looking to recruit from its users, but Ravisankar also noted that he hopes the combined strengths of HackerRank and Mimir will allow students to combine their academic learning with market learning. “This will ensure that they’re equipped with the skills that their future workplaces require,” he said.

Mimir isn’t so much a tool for massive online courses but instead focuses on helping teachers and students manage programming projects and assignments. To do so, it offers a full online IDE, as well as support for Jupyter notebooks, as well as more traditional teaching tools for creating quizzes and assignments. The built-in IDE supports 40 programming languages, including Python, Java and C. There’s also a tool for detecting plagiarism.

Currently, about 15,000 to 20,000 students are using Mimir’s platform for their coursework. That’s dwarfed by the 7 million developers who have signed up for HackerRank so far, but not all of those are active, while, almost by default, all of Mimir’s users will be on the job market sooner or later.

“Mimir has made a name for itself by becoming a secret weapon for computer science programs — Mimir equips them with the tools to make a real difference in the education of developers,” said Prahasith Veluvolu, co-founder and CEO of Mimir. “Working with HackerRank is a natural evolution of our mission, allowing our customers to scale their programs while simultaneously giving students an unmatched classroom experience to prepare them for the careers of tomorrow.”

Powered by WPeMatico

The amount of data that most companies now store — and the places they store it — continues to increase rapidly. With that, the risk of the wrong people managing to get access to this data also increases, so it’s no surprise that we’re now seeing a number of startups that focus on protecting this data and how it flows between clouds and on-premises servers. Satori Cyber, which focuses on data protecting and governance, today announced that it has raised a $5.25 million seed round led by YL Ventures.

“We believe in the transformative power of data to drive innovation and competitive advantage for businesses,” the company says. “We are also aware of the security, privacy and operational challenges data-driven organizations face in their journey to enable broad and optimized data access for their teams, partners and customers. This is especially true for companies leveraging cloud data technologies.”

Satori is officially coming out of stealth mode today and launching its first product, the Satori Cyber Secure Data Access Cloud. This service provides enterprises with the tools to provide access controls for their data, but maybe just as importantly, it also offers these companies and their security teams visibility into their data flows across cloud and hybrid environments. The company argues that data is “a moving target” because it’s often hard to know how exactly it moves between services and who actually has access to it. With most companies now splitting their data between lots of different data stores, that problem only becomes more prevalent over time and continuous visibility becomes harder to come by.

“Until now, security teams have relied on a combination of highly segregated and restrictive data access and one-off technology-specific access controls within each data store, which has only slowed enterprises down,” said Satori Cyber CEO and co-founder Eldad Chai. “The Satori Cyber platform streamlines this process, accelerates data access and provides a holistic view across all organizational data flows, data stores and access, as well as granular access controls, to accelerate an organization’s data strategy without those constraints.”

Both co-founders (Chai and CTO Yoav Cohen) previously spent nine years building security solutions at Imperva and Incapsula (which acquired Imperva in 2014). Based on this experience, they understood that onboarding had to be as easy as possible and that operations would have to be transparent to the users. “We built Satori’s Secure Data Access Cloud with that in mind, and have designed the onboarding process to be just as quick, easy and painless. On-boarding Satori involves a simple host name change and does not require any changes in how your organizational data is accessed or used,” they explain.

Powered by WPeMatico

The world of healthcare has notoriously been described as “broken” — plagued with high-friction workflows, sky-high costs and convoluted business models.

Over the past several years, a long list of innovative startups and salivating venture investors have pinned their focus on repairing the healthcare industry, but its digital transformation still appears to be in the very early innings. After a record-setting 2018, however, digital health investing continued to reach meteoric heights in 2019.

Mammoth pools of capital have flooded into various sub-verticals and business models, backing collections of new B2B and B2C companies focused on optimizing healthcare workflows, improving healthcare access and offering lower-cost distribution models. Over the past two years, digital health startups have raised well over $10 billion in funding across nearly 1,000 deals, according to data from Pitchbook and Crunchbase.

As we close out another strong year for innovation and venture investing in the sector, we asked nine leading VCs who work at firms spanning early to growth stages to share what’s exciting them most and where they see opportunity in the sector:

Participants discuss trends in digital therapeutics, telehealth, mental health and the latest in biotech and medical devices, while also diving into startups improving medical practitioner efficiency, evaluating the evolving regulatory environment and debating valuations and offering a ‘temp check’ on the market for digital health startups leveraging ML.

Although Kleiner Perkins has a long history of investing in iconic health companies, we believe it is still the early innings of digital health as a category today.

When I evaluate new opportunities in the space, I often start by thinking through how the company will move the needle on cost, quality, and access to care — the “iron triangle” of health care systems. Conventional wisdom has been that it’s impossible to improve all three dimensions simultaneously, but we are seeing companies leverage technology to shift this paradigm in meaningful ways.

It’s no longer just a promise. For example, Viz.ai is using artificial intelligence to detect and alert stroke teams to suspected large vessel occlusion strokes, enabling patients to get treatment faster. Their workflows improve access to life-saving care, deliver higher quality through reduced time to treatment (every minute counts as ‘time is brain’ in stroke care), and dramatically reduce the costs associated with long-term disability.

We are also seeing companies provide this type of tech-enabled care outside of the hospital setting. Modern Health is a mental health benefits platform that employers are making available to their employees. The platform triages individual employees to the right level of care, providing clinical care to those with diagnosable depression or anxiety, and making self-guided or preventative care available to everyone else. Their solution improves quality and access by offering mental health services to every employee and reduces the cost associated with untreated mental illness, lost productivity, or employee churn.

Heading into 2020, we’re eager to back digital health companies in new areas that leverage technology to impact cost, quality, and access. A few spaces that I’m excited about are behavioral health (mental health, substance abuse, addiction, etc), care navigation, digital therapeutics, and new models integrating telehealth, remote care and AI to better leverage medical professionals’ time.

Below are some thoughts and coming predictions on health tech broadly:

- Digital therapeutics continue to pick up steam — on the back of Pear and Akili, more companies push to FDA and enter the market. In addition, broader consumer platforms like Calm and Headspace look to broaden their offerings by investigating clinical approvals.

- At least one major pharma looks to expand its consumer surface area by acquiring one of the new digital, consumer-facing generics platform (ex Hims, Ro, NuRx).

- Venture funding for biotech continues to boom with at least three Series A’s of $100M or more in size.

- Drug discovery for neurodegeneration sees a renaissance. High-profile failings of Biogen and the beta-amyloid hypothesis sees a shift of innovation to early-stage biotech and venture creation.

- Big pharma has its DeepMind moment acquiring at least one machine-learning (AI) enabled drug discovery company.

- Clinical trial tech investments heat up; new companies and technologies emerge to make trials patients first and systems get smarter at finding the right patients at their point of care; large incumbents like IQVIA, LabCorp and PPD get acquisitive.

- At least three traditional Sand Hill Road tech venture firms open life science practices or raise dedicated funds.

- Machine learning targets chemistry driven by large advancements in transformer (NLP) models; has the time for computational chemistry finally come?

- HCIT sees a renaissance driven by increased CIO responsibility towards data interoperability. Companies either working on federated ML to allow systems to speak to each other or lightweight edge applications enabling rapid clinical deployment will see quick uptake and traction, until now impossible in HC.

Kristin Baker Spohn, CRV

In the last 10 years, digital health has exploded. Over $16B has been invested in the sector by VCs and we’ve seen IPOs from Livongo, Progyny and Health Catalyst, just in the last year alone. That said, there’s still a lot that mystifies people about the sector — there are spots that are overheated and models that will struggle to deliver venture scale outcomes. I’ve seen digital health evolve first hand as both an operator and investor, and I’m more excited than ever about the future of the space.

A few areas and trends that I’ve been following recently include:

Powered by WPeMatico

OneConnect’s U.S.-listed IPO flew under our radar last week, which won’t do. The company’s public offering is both interesting and important, so let’s take a few minutes this morning to understand what we missed and why we care.

The now-public company sells financial technology that banks in China and select foreign countries can use to bring their services into the modern era. OneConnect charges mostly for usage of its products, driving over three-quarters of its revenue from transactions, including API calls.

After pricing its shares at $10 apiece, the SoftBank Vision Fund-backed company wrapped last week worth the same: $10 per share.

One one hand, OneConnect is merely another China-based IPO listing domestically here in the United States, making it merely one member of a crowd. So, why do we care about its listing?

A few reasons. We care because the listing is another liquidity event for SoftBank and its Vision Fund. As the Japanese conglomerate revs up its second Vision Fund cycle (Vision Fund 2, more here), returns and proof of its ability to pick winners and fuel them with capital are key. OneConnect’s success as a public company, therefore, matters.

And for us market observers, the debut is doubly exciting from a financial perspective. No, OneConnect doesn’t make money (very much the opposite). What’s curious about the company is that it brought huge losses to sale when it was pitching its equity. Which, in a post-WeWork world, are supposed to be out of style. Let’s see how well it priced.

OneConnect targeted a $9 to $10 per-share IPO price. That makes its final, $10 per-share pricing the top of its range. That said, given how narrow its range was, the result doesn’t look like much of a coup for the company. That’s doubly true when we recall that OneConnect lowered its IPO price range from $12 to $14 per share (a more standard price band) to the lower figures. So, the company managed to price at the top of its expectations, but only after those were cut to size.

When it all wrapped, OneConnect was worth about $3.7 billion at its IPO price, according to math from The New York Times. TechCrunch’s own calculations value the firm at a slightly richer $3.8 billion. Regardless, the figure was a disappointment.

When OneConnect raised from SoftBank’s Vision Fund in early 2018, $650 million was invested at a $6.8 billion pre-money valuation, according to Crunchbase data. That put a $7.45 billion post-money price tag on the Ping An-sourced business. To see the company forced to cut its IPO valuation so far is difficult for OneConnect itself, its parent Ping An and its backer SoftBank.

I promised to be brief when we started, so let’s stay curt: OneConnect’s business was worth far less than expected because while it posted impressive revenue gains, the company’s deep unprofitability made it less palatable than expected to public investors.

OneConnect managed to post revenue growth of more than 70% in the first three quarters of 2019, expanding top line to $217.5 million in the period. However, during that time it generated just $70.9 million in gross profit, the sum it could use to cover its operating costs. The company’s cost structure, however, was far larger than its gross profit.

Over the same nine-month period, OneConnect’s sales and marketing costs alone outstripped its total gross profit. All told, OneConnect posted operating costs of $227.6 million in the first three quarters of 2019, leading to an operating loss of $156.6 million in the period.

The company will, therefore, burn lots of cash as it grows; OneConnect is still deep in its investment motion, and far from the sort of near-profitability that we hear is in vogue. In a sense, OneConnect bears the narrative out. It had to endure a sharp valuation reduction to get out. You can see the market’s changed mood in that fact alone.

Photo by Roberto Júnior on Unsplash

Powered by WPeMatico