Fundings & Exits

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

As Google Cloud Next opened today in San Francisco, Accenture announced its intent to acquire Cirruseo, a French cloud consulting firm that specializes in Google Cloud intelligence services. The companies did not share the terms of the deal.

Accenture says that Cirruseo’s strength and deep experience in Google’s cloud-based artificial intelligence solutions should help as Accenture expands its own AI practice. Google TensorFlow and other intelligence solutions are a popular approach to AI and machine learning, and the purchase should help give Accenture a leg up in this area, especially in the French market.

“The addition of Cirruseo would be a significant step forward in our growth strategy in France, bringing a strong team of Google Cloud specialists to Accenture,” Olivier Girard, Accenture’s geographic unit managing director for France and Benelux said in a statement.

With the acquisition, should it pass French regulatory muster, the company would add a team of 100 specialists trained in Google Cloud and G Suite to the an existing team of 2,600 Google specialists worldwide.

The company sees this as a way to enhance its artificial intelligence and machine learning expertise in general, while giving it a much stronger market placement in France in particular and the EU in general.

As the company stated, there are some hurdles before the deal becomes official. “The acquisition requires prior consultation with the relevant works councils and would be subject to customary closing conditions,” Accenture indicated in a statement. Should all that come to pass, then Cirruseo will become part of Accenture.

Powered by WPeMatico

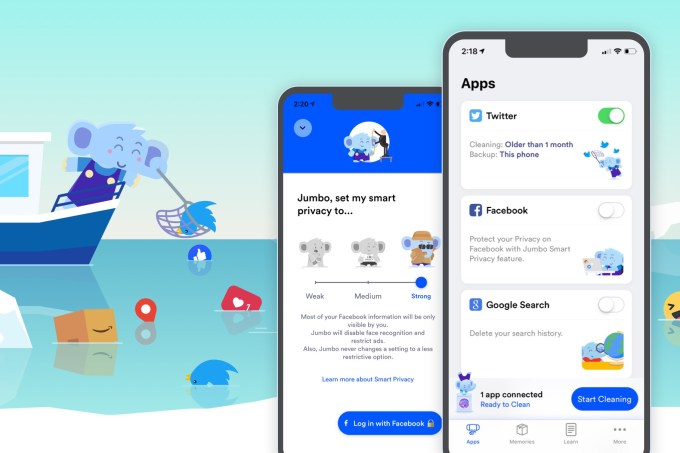

Jumbo could be a nightmare for the tech giants, but a savior for the victims of their shady privacy practices.

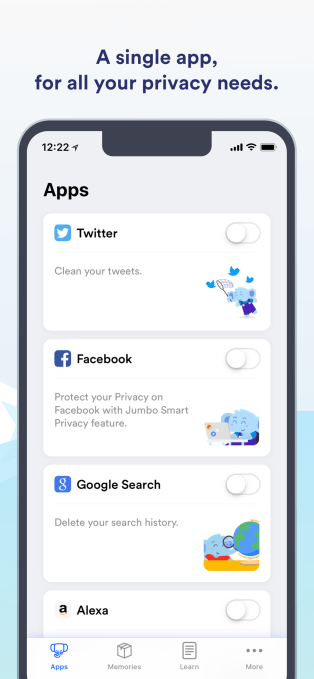

Jumbo saves you hours as well as embarrassment by automatically adjusting 30 Facebook privacy settings to give you more protection, and by deleting your old tweets after saving them to your phone. It can even erase your Google Search and Amazon Alexa history, with clean-up features for Instagram and Tinder in the works.

The startup emerges from stealth today to launch its Jumbo privacy assistant app on iPhone (Android coming soon). What could take a ton of time and research to do manually can be properly handled by Jumbo with a few taps.

The question is whether tech’s biggest companies will allow Jumbo to operate, or squash its access. Facebook, Twitter and the rest really should have built features like Jumbo’s themselves or made them easier to use, since they could boost people’s confidence and perception that might increase usage of their apps. But since their business models often rely on gathering and exploiting as much of your data as possible, and squeezing engagement from more widely visible content, the giants are incentivized to find excuses to block Jumbo.

The question is whether tech’s biggest companies will allow Jumbo to operate, or squash its access. Facebook, Twitter and the rest really should have built features like Jumbo’s themselves or made them easier to use, since they could boost people’s confidence and perception that might increase usage of their apps. But since their business models often rely on gathering and exploiting as much of your data as possible, and squeezing engagement from more widely visible content, the giants are incentivized to find excuses to block Jumbo.

“Privacy is something that people want, but at the same time it just takes too much time for you and me to act on it,” explains Jumbo founder Pierre Valade, who formerly built beloved high-design calendar app Sunrise that he sold to Microsoft in 2015. “So you’re left with two options: you can leave Facebook, or do nothing.”

Jumbo makes it easy enough for even the lazy to protect themselves. “I’ve used Jumbo to clean my full Twitter, and my personal feeling is: I feel lighter. On Facebook, Jumbo changed my privacy settings, and I feel safer.” Inspired by the Cambridge Analytica scandal, he believes the platforms have lost the right to steward so much of our data.

Valade’s Sunrise pedigree and plan to follow Dropbox’s bottom-up freemium strategy by launching premium subscription and enterprise features has already attracted investors to Jumbo. It’s raised a $3.5 million seed round led by Thrive Capital’s Josh Miller and Nextview Ventures’ Rob Go, who “both believe that privacy is a fundamental human right,” Valade notes. Miller sold his link-sharing app Branch to Facebook in 2014, so his investment shows those with inside knowledge see a need for Jumbo. Valade’s six-person team in New York will use the money to develop new features and try to start a privacy moment.

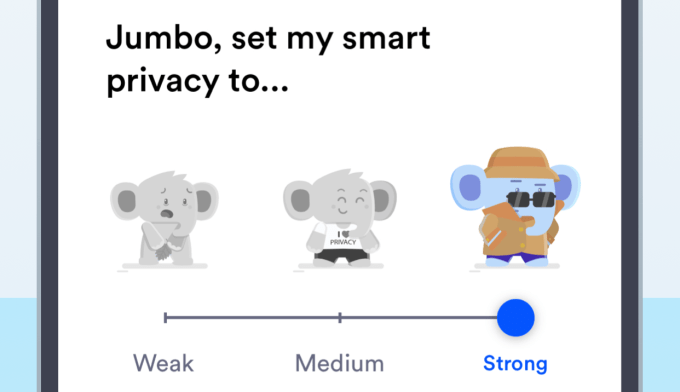

First let’s look at Jumbo’s Facebook settings fixes. The app asks that you punch in your username and password through a mini-browser open to Facebook instead of using the traditional Facebook Connect feature. That immediately might get Jumbo blocked, and we’ve asked Facebook if it will be allowed. Then Jumbo can adjust your privacy settings to Weak, Medium, or Strong controls, though it never makes any privacy settings looser if you’ve already tightened them.

Valade details that since there are no APIs for changing Facebook settings, Jumbo will “act as ‘you’ on Facebook’s website and tap on the buttons, as a script, to make the changes you asked Jumbo to do for you.” He says he hopes Facebook makes an API for this, though it’s more likely to see his script as against policies.

.

For example, Jumbo can change who can look you up using your phone number to Strong – Friends only, Medium – Friends of friends, or Weak – Jumbo doesn’t change the setting. Sometimes it takes a stronger stance. For the ability to show you ads based on contact info that advertisers have uploaded, both the Strong and Medium settings hide all ads of this type, while Weak keeps the setting as is.

The full list of what Jumbo can adjust includes Who can see your future posts?, Who can see the people?, Pages and lists you follow, Who can see your friends list?, Who can see your sexual preference?, Do you want Facebook to be able to recognize you in photos and videos?, Who can post on your timeline?, and Review tags people add to your posts the tags appear on Facebook? The full list can be found here.

For Twitter, you can choose if you want to remove all tweets ever, or that are older than a day, week, month (recommended), or three months. Jumbo never sees the data, as everything is processed locally on your phone. Before deleting the tweets, it archives them to a Memories tab of its app. Unfortunately, there’s currently no way to export the tweets from there, but Jumbo is building Dropbox and iCloud connectivity soon, which will work retroactively to download your tweets. Twitter’s API limits mean it can only erase 3,200 tweets of yours every few days, so prolific tweeters may require several rounds.

Its other integrations are more straightforward. On Google, it deletes your search history. For Alexa, it deletes the voice recordings stored by Amazon. Next it wants to build a way to clean out your old Instagram photos and videos, and your old Tinder matches and chat threads.

Across the board, Jumbo is designed to never see any of your data. “There isn’t a server-side component that we own that processes your data in the cloud,” Valade says. Instead, everything is processed locally on your phone. That means, in theory, you don’t have to trust Jumbo with your data, just to properly alter what’s out there. The startup plans to open source some of its stack to prove it isn’t spying on you.

While there are other apps that can clean your tweets, nothing else is designed to be a full-fledged privacy assistant. Perhaps it’s a bit of idealism to think these tech giants will permit Jumbo to run as intended. Valade says he hopes if there’s enough user support, the privacy backlash would be too big if the tech giants blocked Jumbo. “If the social network blocks us, we will disable the integration in Jumbo until we can find a solution to make them work again.”

But even if it does get nixed by the platforms, Jumbo will have started a crucial conversation about how privacy should be handled offline. We’ve left control over privacy defaults to companies that earn money when we’re less protected. Now it’s time for that control to shift to the hands of the user.

Powered by WPeMatico

Zoom, the only profitable unicorn in line to go public, priced its initial public offering at between $28 and $32 per share Monday morning. The video conferencing business plans to trade on the Nasdaq under the ticker symbol “ZM.”

Zoom, valued at $1 billion in 2017, initially filed to go public in March. According to its amended IPO filing, the company will raise up to $348.1 million by selling 10.9 million Class A shares. The offering will grant Zoom a fully diluted market value of $8.7 billion, a more than 8x increase to its latest private market valuation.

Although the company has garnered praise for its stellar financials — Zoom posted $330 million in revenue in the year ending January 31, 2019, a remarkable 2x increase year-over-year, with a gross profit of $269.5 million — the road to IPO hasn’t been without hiccups.

The company’s founder and chief executive officer Eric Yuan last night published an open letter concerning the conduct of Zoom’s chief financial officer Kelly Steckelberg. According to the letter, Zoom was recently informed by an anonymous source that Steckelberg had an “undisclosed, consensual relationship” during her tenure at a previous employer.

Steckelberg was most recently the CEO of the online dating site Zoosk; before that, she was a senior director in consumer finance at Cisco . The letter does not specify where the relationship took place, when or with whom.

Losing a CFO mere days before an IPO would have been a major loss for Zoom. CFOs often become the face of the IPO, handling the grueling tasks associated with crafting an IPO prospectus, leading the roadshow and more, while also maintaining day-to-day financial operations.

Yuan writes that the Zoom’s board of directors conducted a full investigation into the matter and determined that Steckelberg would stay on as Zoom’s CFO: “Kelly expressed regret for what transpired at her former employer, took ownership for the situation, and made clear to us that she had learned valuable lessons from the experience,” he wrote.

“We appreciated Kelly’s openness and candor during this process,” he continued. “It is clear that this matter related only to circumstances at her former employer. During Kelly’s tenure at Zoom, she has been an incredible contributor, as well as a model steward of our culture, values, and high standards since joining the Company.”

We reached out to Zoosk for comment. Zoom declined to comment further.

Zoom, expected to make the final call on its IPO price next Wednesday, will likely price at the top of the range and see a clean pop on its first day on the markets given its clean track record and positive financials. The business was founded in 2011 by Eric Yuan, an early engineer at WebEx, which sold to Cisco for $3.2 billion in 2007. Before launching Zoom, he spent four years at Cisco as its vice president of engineering.

Zoom has raised $145 million to date from investors, including Emergence Capital, which owns a 12.2 percent pre-IPO stake; Sequoia Capital (11.1 percent pre-IPO stake); Digital Mobile Venture (8.5 percent), a fund affiliated with former Zoom board member Samuel Chen; and Bucantini Enterprises Limited (5.9 percent), a fund owned by Li Ka-shing, a Chinese billionaire and among the richest people in the world.

Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs are leading its offering.

Powered by WPeMatico

As more universities turn to offering online degrees to expand their student bodies by way of cyberspace, one of the pioneers in enabling that trend has made an acquisition to expand into new territory around skills training and continuing education. 2U, which helps build online degree programs for a number of top universities, is paying $750 million to acquire Trilogy Education, which creates online and in-person “boot camps” — continuing education programs — in collaboration with universities to train those already in the workforce with tech skills in areas like coding, data analytics, UX/UI and cybersecurity.

The deal, which is expected to close in the next 60 days, is coming in a combination of cash and shares — $400 million in cash and $350 million in newly issued shares of 2U common stock — the company said. It’s a decent exit for Trilogy, which was valued at $545 million (according to PitchBook) when it raised $50 million in June 2018. Its investors include Highland Capital, Macquarie and Exceed, among others.

2U, meanwhile, has a market cap of $3.85 billion and is publicly traded on Nasdaq.

The acquisition helps 2U consolidate its university footprint, which will get bumped up to 68 from its previous 36. And it presents an obvious opportunity to up-sell and cross-sell: those who are already jumping into building degree programs can diversify into more skills training, while those who have yet to build full degree services but have created skills training programs now might consider how to parlay that experience into degrees — all from one provider, 2U. This also opens more generally a bigger window for 2U to expand into the continuing education market, which it estimates is worth some $366 billion.

It also helps it better compete with other companies that have already built a dual-track approach to online education, building degrees as well as short courses, like Coursera (Udacity and Udemy are among those that have focused on further education).

“[Trilogy Education] is a natural strategic fit and growth driver for 2U that will extend our reach across the career curriculum continuum, deepen our relationships with new and existing partners, drive marketing efficiencies, and open a more direct corporate training and enterprise sales channel for the company. We expect the addition of Trilogy to accelerate our path to $1 billion in revenue by one year from 2022 to 2021,” 2U co-founder and CEO Christopher “Chip” Paucek said in a statement. “Increasingly, universities are attempting to add practical, technical skills to their degrees. We simply future-proof the degree by adding this type of technical competency.”

The presence of commercial companies building educational courses for nonprofit universities, and taking a cut in the process, has seen more than a little controversy. The business spin that is put on education through these programs not only calls into question how and what schools (and their partners) prioritise in the curriculum, but they raise issues around how higher education is priced, and who profits from these degrees — which sometimes can still cost more than $60,000, despite no physical time in classrooms. (There is an excellent dive into the issue here in the Huffington Post, featuring an interview with the co-founder of 2U, John Katzman, who also founded the Princeton Review.)

To be fair, some of the issues around higher education — such as the exorbitantly high cost in some countries, and the fact that it still feels like a largely elitist endeavor with the odds of students gaining acceptance and achieving in top universities still in favor of too-small a privileged subset of families — cannot be completely tied to the development of online learning courses powered by for-profit companies.

And you could also argue that this was bound to be the next step, given how technology has evolved across all of education, and the fact that edtech is not a core competency for many institutions.

One of the potential positives that comes out of online degree programs is that it gives opportunities to a much wider group of would-be students, and mass market is something that Trilogy knows: it has to date already provided courses for 20,000 people and 1,200 instructors across 120 programs, it says, with an emphasis on practical skills to bring up local workforces, and working with universities to build these courses and connecting with big companies — customers include Google, Microsoft and Bank of America — to deliver them.

“By joining forces with 2U, Trilogy Education can empower universities to reach more students, in more places, throughout more of their lives, while driving positive economic impact in their local regions,” Trilogy Education CEO and founder Dan Sommer said in a statement. “Trilogy and 2U share a belief that universities are critical to lifelong learning and to meeting the workforce development needs of local economies both domestically and internationally, and we’re proud to further our mission and continue this important work as part of the 2U family.

Powered by WPeMatico

Just five months after announcing £85 million in Series E funding, Monzo is already gearing up to raise additional funding, which would almost double its valuation.

As reported in the Sunday Times yesterday, the U.K. challenger bank is close to raising £100 million in further funding in a new round led by an unnamed U.S. investor. If the deal goes through, it will reportedly give Monzo a pre-money valuation of close to £2 billion, up from £1 billion in October.

Now TechCrunch has learned that the new U.S. backer is Y Combinator.

According to multiple sources within investor circles on both sides of the pond, the Silicon Valley accelerator and venture capital fund plans to invest in Monzo out of its growth fund, the vehicle it typically uses to double down on fast-growing companies within its alumni.

Notably, Monzo isn’t a graduate of YC. However, Monzo co-founder Tom Blomfield’s previous startup, the payments company GoCardless, did go through the accelerator program, making Blomfield himself an alumni.

Monzo declined to comment. Y Combinator couldn’t be reached at the time of publication and I’ll update this post should I hear back.

Meanwhile, the news that Y Combinator is lining up to invest in Monzo makes a lot of sense in a number of ways beyond Blomfield’s previous ties to the accelerator. The challenger bank already boasts a plethora of U.S. investors, such as U.S. venture capital firm General Catalyst, Thrive Capital and Stripe.

And, as TechCrunch reported exclusively, Monzo has quietly begun working on a U.S. launch. This includes setting up a small team states-side to begin laying the groundwork to bring a version of Monzo to North America. It will initially be powered by a U.S. banking partner while Monzo works on the necessary regulatory licenses to go it alone.

Monzo continues to grow at a clip here in the U.K., too. To date, the challenger bank claims more than 1.7 million customers since it launched in 2015.

Powered by WPeMatico

Extra Crunch offers members the opportunity to tune into conference calls led and moderated by the TechCrunch writers you read every day. This week, TechCrunch’s Kirsten Korosec and Kate Clark led a deep-dive discussion into Lyft’s IPO and the outlook for the business going forward.

After skyrocketing nearly 10% on its first day hitting the public markets, Lyft stock has faded back down towards its IPO price as some investors grow more concerned over the company’s path to profitability (or lack thereof) and the long-term fundamentals of the business. But Lyft’s public listing is bigger than just the latest in increasingly common unicorn IPOs. As the first public “transportation-as-a-service” company, Lyft offers the first inside glimpse into the business model and its economics, and its development may ultimately act as the canary in the coal mine for the future of transportation.

“Lyft, hasn’t just survived, they’ve grown. 18.6 million people took at least one ride in the last quarter of 2018. That’s up from 16.6 million in late-2016. That illustrates the growth that the company has had. They’ve also said that they have 39% share of the ride-sharing market in the US. That’s up from 22% in 2016.

To me, the big question is let’s say they had Uber’s share, which is 66%, would they be able to make a profit? Is that the determination? And I’m not convinced that it is, which is why all these other aspects of the transportation-as-a-service business model [micromobility, AVs, etc.] are going to be really important.”

Image via Getty Images / Mario Tama

Kirsten and Kate dive deeper into what the market response to Lyft means for Uber and the timeline for its impending IPO. The two also elaborate on their skepticism of ride-hailing economics and debate which innovative transportation model will ultimately drive the path to profitability for Lyft, Uber and others.

For access to the full transcription and the call audio, and for the opportunity to participate in future conference calls, become a member of Extra Crunch. Learn more and try it for free.

Danny Crichton: Good afternoon and good morning everyone this is Danny Crichton, executive editor of Extra Crunch. Thanks so much for joining us today with TechCrunch reporters Kate and Kirsten.

I’ll start with a quick introduction for our two writers today. We have Kate Clark, our venture capital reporter. Kate has been with us for a while now covering everything in the startup and venture world. She’s also one of the hosts of TechCrunch’s podcast Equity and also writes our Startups Weekly newsletter.

Our other writer today is Kirsten, our intrepid automotive writer covering all things Elon Musk, Tesla, and everything else in the autonomous vehicle space. Kirsten has also been with us for quite some time and also writes a newsletter that she just introduced in the last couple of weeks, around transportation. So with that, I’m going to hand off the conversation to the two of them now.

Kirsten Korosec: Thanks so much Danny. This is Kirsten Korosec here. The newsletter is in a bit of a soft launch but it is being published Fridays and we hope to have an email subscription coming sometime in the future, so just keep an eye out for that.

I should also mention I too have a podcast centered around autonomous vehicles and future transportation called The Autonocast that comes out weekly. Thanks so much for joining the call and just a reminder, we want participation. So at about the halfway point, we’ll turn and open up the line and answer questions. Let’s get started.

Before we dig into all the hot takes out there, I think it’s worth providing a primer of sorts — a general timeline of events. We all probably know Lyft of course and most of us think of 2012 as the launch date when it came to San Francisco, but really Lyft was build out of the service of Zimride. Which is the ride-sharing company that John Zimmer and Logan Green founded in 2007.

A lot of attention has been placed on Lyft in 2018 with what happened in the past year, in the run-up to the IPO. But I think it is worth noting the intense activity and growth that happened between 2014 and 2016. These are critically important years for Lyft, just a frenzy of activity in a period where the company gained ground, investors, and partners.

To showcase the amount of activity that was happening; Lyft had two separate funding rounds, one for $530 million another for $150 million, just two months apart in 2015. You might also recall in early-2016 its partnership with GM and the automakers’ $500 million dollar investment as part of the Series F $1 billion dollar fundraising effort.

That was really interesting because GM’s president at the time Dan Ammann took a seat on the board, which he has since vacated. As Lyft and GM started realizing that they were competitors. Now, Dan is the CEO of GM Cruise which is the self-driving unit of GM.

2017 and 2018 were also big years, as Lyft launched their first international market in Toronto. They made big moves on the autonomous vehicle front, which we’ll talk about today, and in micromobility. Their scooter business launched in Denver in 2018. They bought Motivate, which is the oldest and largest electric bike share company in North America. Then, we finally get to the end of 2018, and this is when Lyft confidentially files a statement with the FDC and we’re off with the races to the IPO.

The last two months or three months is when Lyft unveiled its prospectus, met with investors, priced its IPO and made its public debut. So Kate what are the nuts and bolts of the IPO and what’s happening right now?

Kate Clark: Hi everybody this is Kate. So I’m just going to mention really quickly the timeline these last couple of months in the run-up to Lyft’s highly historical IPO. So going back to December, that’s when Lyft initially filed confidentially to go public. We later find out that they are going public on the NASDAQ when they eventually unveiled their S1 in early March.

This is after Lyft had raised $5 billion in debt and equity funding at a $15 billion dollar valuation, so there are a lot of people paying attention to what was the first ever rideshare IPO. So then in early-March, we’re able to get a closer look at Lyft’s S1, which tells us that the company has $911 million in losses in 2018 and revenues of $2.2 billion. So after calculating and pulling together some data, a lot of people were quick to find out that that means Lyft has some of the largest losses ever for any IPO. But also has some of the largest revenues ever for any pre-IPO company, just following Google and Facebook in that category.

So this is a really interesting IPO for a lot of people given these sky-high losses but also these huge, huge revenues. The next we see Lyft price their IPO between $62 and $68 dollars a share. Some people were quick to say that that was maybe a little underpriced, given that this was a highly anticipated IPO with a ton of demand. So on the second day of Lyft’s roadshow, the process, they say that their IPO is oversubscribed. So demand is apparently huge, their oversubscribed, so they decide we’re going to increase the price of our shares.

Image via GettyImages / maybefalse

So Lyft then says they gonna charge a max of $72 per share and then on the day of their IPO they charge $72 per share, the next day opening at $87 per share. So we see a huge IPO pop that I don’t think was particularly surprising given that they already spoke of this demand, and we had already known that there was a lot of demand on Wall Street. Not just for Lyft but just for unicorn IPO’s of this stature, given that there are so few of these. So Lyft began trading hitting $87 per share though, if you’ve been following the news that’s not were Lyft is today.

Kirsten: Yeah so I was just about to ask — Kate give me the latest numbers, you know a lot of focus is on that opening day but things haven’t exactly sustained. So what’s happened in the past few days?

Kate: Yeah it’s really tough to manage expectations after an IPO. I mean, I think there has been a lot of criticism towards Lyft now and I think it’s trading below its initial share price. So as I mentioned Lyft opened at $87 per share, it priced at $72, but almost immediately they began trading below that $72 price per share. So they closed Tuesday trading at $68.96 per share. Still boasting a market cap larger than $19 billion. So they’re still significantly valued at more than they were as a private company at $15 billion but it doesn’t look good to be trading below a price per share so quickly.

However, it actually did hit its IPO price for just a minute today, so maybe let’s give it a few more hours and see where it closes. It’s possible that it will sort of jump towards that $72, but it’s still trading quite significantly below that $87.

Kirsten: With IPOs like this, and especially such a high profile one, there’s going to be a ton of attention on share price and on volatility. And so I’m wondering, in your view, what did this first week, or first few days of volatility say to you? What does it say about Lyft’s future and, well certainly, its present?

Kate: Yeah. I mean, it’s hard to say. I think a lot of people were questioning if Wall Street was going to be interested in a company like Lyft that’s extremely unprofitable at this time and has years left before it will reach profitability, if indeed it ever reaches profitability.

So at this point you got to wonder, do some of these investors that did buy Lyft right off the bat, were they really long on Lyft? Because it does look like a lot of those investors have already sold their stock and perhaps weren’t as invested in Lyft’s long-term profitability plan, which involves a lot of very iffy things, like the future of autonomous vehicles, which we’ll talk about later in this call. And there’s a lot of uncertainty there.

But with that said, it’s not uncommon for a stock to experience volatility right off the bat, and you can’t assume the future of that stock price just because of some early volatility.

And we gathered some examples of IPOs where there was some early volatility that did not determine the long term future. So Carvana, for example, which is an online used car dealer in the automotive space, and it did experience volatility at first, with the stock sliding in the first few months but ultimately trended upward.

Kate: So Carvana opened at $13.50 a share, falling below its IPO price, so it didn’t even have the IPO pop. And then in 2018, it hit an all-time high of $65 per share. Today, it’s trading around $58 per share, so that’s ultimately a positive story to be told there.

And then another example on the other side of things is Snap, which actually took four months to dip beneath its 2017 IPO price, and we all know Snap has definitely not been a success story and it’s trading well below its offer price. But then finally, Facebook, for example, dropped below its IPO price on its second day of trading and then actually had a rough first year on the stock market before the stock ultimately took off and became a very obvious success.

Kirsten: So, Kate, I’m wondering why you think that there was that initial run up on that first day. Was it excitement? Was there something material that was pushing the price up? What was the cause?

Kate: I think there was a lot of excitement and demand around this IPO because it was very much one-of-a-kind, and there were a lot of investors that it seemed were really long on the possibility of Lyft becoming this hugely profitable company. And I think a lot of that was because in the S1, although you did see these really, really big losses — quite major, just ridiculously huge losses — you did see that they were shrinking over time and that there was definitely a path in which Lyft could take where it would reach profitability, say, in the next five years.

And I think Wall Street was really paying attention to that, and they were not paying attention to some of the other metrics. Now, they’ve taken off their rose-colored glasses and they’re looking at Lyft as a public company, and it’s just a little bit different now that it’s actually completed its debut.

Kirsten: Well, so, I mean, I like to view IPOs often times, and especially in Lyft’s case, as a measure of an investors’ faith in the company’s growth prospects, because this is a company that while it does have quite a bit of revenue, it has significant losses and it’s really planning not just for the present day but for the future. It’s been called a disruptive business for a reason, and it is certainly very forward-looking. So I’m wondering if you think it was a good strategy for Lyft. They wanted to open it up to “the everyman” when they actually went to market. They did a different approach, and do you think this might have had an effect? I mean, it’s very on-brand for them to do this, but I’m wondering if you thought that means that some of the investors aren’t as disciplined.

Kate: Do you mean with the fact they were providing bonuses to their employees and drivers to actually participate in the IPO as well?

Kirsten: Absolutely. That’s actually a really good point that maybe you can elaborate on. Lyft did a little bit of a more open approach for its IPO. Typically IPOs can be closed off to only large, institutional investors. So did this set them up perhaps to have more volatility?

Kate: Yeah, Lyft provided some of their drivers up to, I think, $10,000 to, in theory, actually buy stock in the IPO. Do I think that had a high impact? I don’t know. I think there’s not enough comparison, not enough data to really make a decision or to make a hot take on whether that really was part of the volatility. I think just given the uncertain nature of Lyft’s future and their big losses, I think their volatility was pretty inevitable, and I think people paying attention to this are probably not particularly surprised by how the stock has fared in these first couple days.

And I do want to add there’s this six-month lock-up period for the venture capital funds that own Lyft and as well as their employees, so I think we’re not sure what’s going to happen when that lock-up period ends and those holders can just sell their stock right then or how that will impact the stock price, as well.

Image via TechCrunch/MRD

Kirsten: So something to keep an eye on. It reminds me a lot of a company I write a lot about, which is Tesla, and I’ve been covering them for years. And it’s one of the most volatile stocks, and their investors, they certainly have large, institutional investors, but the number of fanboys that they have with smaller investors, either prop up the share price sometimes or add to that volatility, and I’m kind of really curious to see if that happens with Lyft. If you go to a shareholder meeting at Tesla, for example, it’s filled with people who are passionate about the brand and its CEO, Elon Musk.

And Lyft and possibly Uber, if they end up finally going through with their IPO, you can see that potentially happening because people feel very strongly about the brand and also the service it provides. So I’m curious to see how this all sort of shakes out. And I tend to take the view that I invest personally in mutual funds and things like that. I don’t invest in any of these companies, but the long, patient view tends to be the better one, and trying to catch a falling knife, as investors have told me, is never really a good idea.

So I’m curious to see if investors sort of grow up and learn with Lyft, if they’ll become disciplined and just sort of wait it out and see them play out the growth prospects for the company in the long term. So, we’ve been talking about Lyft and I can’t not talk about Uber as a result. I’m wondering what you think this might mean for Uber. The big story initially was let’s beat Uber to IPO and I’m wondering what this means then. Is this indicative of what Uber is going to experience?

Kate: I think that question is really at the top of everyone’s mind right now, including my own. I will say that I still do think it was highly beneficial for Lyft to get out first. Because imagine if and when Uber does too experience volatility, which it probably will, if it were to have gone first, I think that would have frightened Lyft a lot more than Lyft’s volatility may or may not be frightening Uber. So, with that said, I think I’m of two minds right now with my thoughts on how this impacts Uber’s IPO. I think that if Lyft stock continues to be volatile and perhaps even falls lower than it already has. I do think that there is a chance Uber may ultimately decide to push its IPO back.

I think that for a few reasons, namely being that Uber is not in a huge rush to go public. They do have the ability to wait. They have filed to go public. So it’s likely to happen quite soon, but it may not happen in April as they are reportedly planning to do.

On the other hand, Lyft went public at like a $24 or $25 billion dollar market cap. Whereas Uber is going to debut at maybe a $120 billion dollar initial market cap. So these IPOs, although they are both ride hail IPOs and they are very similar companies in a lot of ways, they’re also very different and Uber is operating on an entirely different scale though it still is unprofitable. And has some of the same issues that, investors are probably noting about Lyft.

I think it’s either going to be that it’s maybe that they do decide to push it back or maybe that Uber is like, well we’re five times larger, six times larger. We have much larger statistics to show to investors. There’s just a chance it could go either way. I wish I had a better, more concrete answer, but I just don’t think we know yet.

Kirsten: Well I’m okay with not taking hot takes just a few days into this IPO. I think this is a good time to open it up to questions. While we wait for a question, I will do one quick follow up with you Kate. What do you think this means for Uber? Will it delay its IPO?

Kate: Right now, no, I don’t think they’re going to. But it’s like I said, it’s tough to say given that it’s only been a few days of Lyfts IPO. But no, I think you’ve got to imagine that they are ready to discuss the possibilities of Lyfts IPO and already planned ahead if there was volatility. They maybe already assumed that would happen, given that that’s not uncommon. So right now I’m going to say no, I don’t think they’re going to delay, but it’s certainly still a possibility.

Kirsten: Okay, great. I think another really interesting piece for Uber was their acquisition of Careem. This is a deal that was made right before their IPO, so it was shifting attention away from Lyft, just for a moment.

Why did Uber do this? Is this not a signal that they’re delaying their IPO? Is this just prepping for it? What are you hearing on it? I’m wondering if this might have just been a strategy to show the world investors, specifically potential shareholders, what the road ahead is going to look like. Or is it some other reason — Is it to justify their really big losses?

Image via Careem / Facebook

Kate: I think it’s the latter two things you said. Just to give some background Uber is paying about $3.1 billion to acquire Careem, which is a Middle Eastern ride-hailing company. So basically just the Uber of the Middle East. Uber does have a history of acquiring, smaller competitors like this in different markets where it’s not active, just as a way for Uber to quickly grow essentially.

So I do think it’s a big deal to make just before going public. So I guess we don’t know if they necessarily will go public in April, but I think it was a move to present to public market investors as a prep for an IPO, to show “we just acquired this company, here’s more evidence of future growth”. Like you mentioned, it’s definitely a justification of those huge losses that we know Uber has.

Kirsten: Thanks for that. Questions?

Caller Question: Hi there, so when we talk about looking ahead and moving towards profitability — what role, if any, do you think the acquisition of a scooter or other mobility companies will have for companies like Lyft and Uber?

Kirsten: That’s a great question. I think it’s going to be a huge piece of both of their businesses. A lot of people describe this as the first ride-hailing IPO. We need to stop calling this a ride-hailing company. These are transportation-as-a-service companies and they’re making money. But generating revenue as opposed to making profit is a totally different thing. When you start talking about ridesharing, it’s a tough business. With those it’s an asset-light business, right? They don’t own the cars and then they technically don’t employ these drivers.

But at the same time, as of 2016 only something like 1% of people in the US were using rideshare. So you see this opportunity, but they’re not pushing forward. There is a ton of car ownership still that’s happening. Yes, sharing has absolutely increased, but 17 million new cars were sold in the US last year. So scooters, bike share and other businesses are going to be key to their paths to profitability because ride-sharing alone is just difficult to make a profit. It’s not difficult to generate revenue. It’s difficult to make a profit on.

And I’m wondering, talking about that road to profitability, I do think it’s worth noting how much they have grown. Lyft, hasn’t just survived, they’ve grown. 18.6 million people took at least one ride in the last quarter of 2018. That’s up from 16.6 million in late 2016, that illustrates the growth that the company has had.

They’ve also said that they have 39% share of the ride-sharing market in the US. That’s up from 22% in 2016. To me, the big question is let’s say they had Uber’s share, which is 66%, would they be able to make a profit? Is that the determination? And I’m not convinced that it is, which is why all these other aspects of the transportation-as-a-service business model are going to be really important.

Kate: I think what you pointed out is important, about Lyft and Uber both becoming transportation businesses, not ride-hailing companies and I think their long-term visions involve scooters, bikes, autonomous vehicles, all sorts of different models of transportation beyond just car sharing.

Kirsten: I hate to be wishy-washy here and say, I don’t know, but I do really think that it’s going to come down to a variety of items all coming together. It’s just not going to be enough for Lyft to scale up its ride-hailing business. And I should point out that Uber should be treated in some ways the same way, but there are some distinct differences. But it’s important for us to think of Lyft as a transportation-as-a-service business. I mean they say in their prospectus that transportation is a massive market opportunity. The hard part of course is turning that into a profit. There might be opportunity there.

So there’s this asset-light business that they have right now, which is the ride-hailing, but then they are making acquisitions in the micromobility space and that is going to become more capital intensive. And that’s going to force them to change their business. And then there’s the autonomous vehicle piece. And then finally, I actually think that one of the pieces of their S1 that has really not received much attention at all is what they’re pursuing in terms of public transportation. And they have said that they, and Uber, intend on being a piece of the public transit ecosystem.

Now that doesn’t mean that they’re going to necessarily be operating buses, but there are people that I’ve talked to in the industry who actually feel like, in Uber’s case, they want to control every mode of transportation. For Lyft, I see them seeing more of the opportunity financially with the data piece and becoming more of a platform and becoming that one-stop shop where you use an app to figure out if you want to use the scooter or a bike, or ride-hailing or buy that ticket for the L in Chicago or the Bart System.

So I really think that the public transit piece often gets ignored and cities are having so much more control now and weighing in. We see this in New York City with congestion pricing. It’s going to force Lyft and Uber to take advantage of these opportunities and use their platform in a way that perhaps accelerates faster than they had intended.

Kate: I’m very interested in the public transportation element, but I’m also very skeptical of the scooters and bikes in the future for Lyft, I think, given the unit economics, I certainly wouldn’t rely on them to be Lyft’s path to profitability. I think autonomous vehicles are a much more interesting path towards profitability. So a lot of companies, Uber, Lyft, Waymo and more are focusing on autonomous vehicles and their development, whether that be with hardware or software. How does Lyft’s strategy with autonomous vehicles differentiate from some of their competitors or does it does differentiate?

Kirsten: It does differentiate, and the funny thing is, is that so you don’t see micromobility necessarily as the oath to profitability and are interested in AVs and I write about AVs, but I see that AVs as a harder path to profitability in a way because of the nuts and bolts that it takes to develop them.

So just to weigh in really quickly on the micromobility piece and then I’ll move on to AVs; To show the opportunity but also the volatility in a real-world example for micromobility, I was in Austin for South by Southwest, I think you were there too, and you probably saw scooters everywhere, right? 18 months ago there were no scooters or bike share in the city. Then bike share came first.

Image via Flickr / Austin Transportation / https://www.flickr.com/photos/austinmobility/41536051644/in/album-72157669223418248/

And I was talking to that mayor of Austin and one of the folks from Spin, which is a Ford owned business, and they told me something that was really remarkable that I hadn’t thought about, which was that scooters were disrupting the bike share business. So bikes share came in and then scooters came in and all of a sudden they’re pulling bikes off the streets because no one was using them or were not using them at the same level as scooters.

Lyft is going to go through these same exact growing pains and people are figuring out what works. And as you mentioned, the unit economics are an issue, the wear and tear on the scooters alone is driving up costs and driving down revenues certainly, but pretty much making it very difficult to make a profit on it.

But that’s a near term business, right? So it’s at least generating revenue right now. On the other hand, you have this other piece, which is the AV piece. Lyft is doing some really interesting things on the AV piece — they kind of have a two-prong approach.

So they basically created a ton of partnerships to use their platform. So this started a couple of years ago and companies like Aptiv, drive.ai, even Waymo and nuTtonomy, which Aptiv just recently bought about a year ago and GM, and Lyft basically allows developers to use their platform and connect to their autonomous vehicle and offer these rides.

And the best example of this, if you’ve been to CES or if you have been to Las Vegas I should say more specifically, is this partnership that Lyft has with Aptiv — and Aptiv as a tier one supplier, they used to be called Delphi, they spun out, they bought nuTonomy, and they’re Aptiv now. And this is taking Aptiv automated BMW, which are on the Lyft network. If you hail a ride, you might be asked if you want a self-driving car, or “are you okay with a self-driving car?” And they have a safety driver, no humans have been pulled away from it yet. But they provided about 35,000 rides since I want to say January 2018.

Then they’re also doing Level 5, a dedicated self-driving vehicle division that launched in 2017. And here they’re basically creating an open self-driving system or open SDS. On top of that, they have partnered with Magna, an auto parts producer, to develop these self-driving systems that can be manufactured at scale.

And so you just see a rush of partnerships and sort of dual approaches and all of that costs a lot of money. And I can’t emphasize the amount of money that it costs or will cost to develop these systems and deploy them commercially. And I hear from other companies figures like $5 billion to get self-driving vehicles. So developing the full stack, doing fleet management, maintenance, all of that — that’s a lot of money. And, I’m not sure where Lyft, will get that capital, will they get it from the open market or will they have to go and ask for more capital.

Kate: So when do you think then that Lyft will be able to commercialize autonomous vehicles?

Kirsten: The timeline? So depending on who you talk to, you can hear from any of these developers between five years and 30 years. I think it’s important to talk about language and how we talk about autonomous vehicles. So to be clear, there is currently not a single commercial autonomous vehicle deployment where a human being or safety driver has been pulled away from the wheel. It just doesn’t exist.

There are plenty of pilots and Waymo is probably considered the leader in that list, though it is a bit of a confusing one for me because they have so many partnerships and they’ve become competitors to some of those partnerships. The analogy I use is “Survivor,” the reality show. Everyone wants to make these alliances so they don’t get voted off the island.

And now we’re at that point where autonomous vehicle development has entered what we call the trough of disillusionment, which is heads down, “let’s get away from the hype, let’s do the hard work.” And I think we’re going to see a lot of those partnerships and headwinds really come up in the next year, 18 months. So to put a target date on Lyft, it’s really going to depend on which one of those partnerships really play out and are real. I think the one with Aptiv seems the most real to me based on what I know the company is doing and I can see them doing a lot more pilots in the next 18 months.

Does that mean commercial deployment without a human safety driver behind the wheel? I’m not sure I can see a lot more these pilots with a human safety driver expanding beyond Las Vegas. I see pilots happening absolutely in the next year to 18 months. The issue is going to be when is that human safety driver going to be pulled out and with which partner.

Kate: So should we open it up to questions again?

Caller Question: Hi, I was just wondering how we should think about the regulatory risks that might exist as these companies expand to new cities, new markets, or even the public transport use case you mentioned. Thanks.

Kirsten: The regulatory piece is an interesting one. Let’s talk about ride-hailing first. We’ve already seen the regulatory environment, in cities, push back against companies like Uber and Lyft. I think the congestion pricing model that just launched in New York City is going to be one to watch and could be something that will put pressure on, on businesses like Lyft.

Kate: I agree and just to speak, quickly on the scooters; I think the narrative around scooters has been pretty dominated by how cities have forced them out or cities push these strict regulatory barriers on them. And I think that’s still playing out very much. There are even some scooter providers that have had to pull out of cities that they worked very hard to get into in the first place. So I think that has slowed down some of the growth there. And given that Lyft has micromobility as such a key part of their road to profitability, I think that’s partially why I am a little bit skeptical of how that’s gonna play out.

Kirsten: One thing we’ve found, and something to consider for Uber as well, in the future, if any of these AV developers end up, filing for IPOs on their own — there’s been chit chat about Waymo someday doing that or GM cruise someday— the implications for all of these companies and their relationship with cities should not be ignored or undervalued.

And I think you see a bit of that playing out with the present day track we have, which is the ride-hailing scooters and bike share cities and transit agencies or the DOT of different counties finding that they are in a more powerful position than they’ve ever been before. And they are exerting that power.

And so you will see instances like Los Angeles where they have put forth a mandatory data sharing component if you want to operate in their city. This raises some privacy concerns by the way, but it also adds another cost to a company or certainly forces them to look at their business a little bit differently.

Then you start talking about AVs and where are they will operate, how they will operate, where are they will park, what type of vehicle will be allowed in the urban center. In places like Europe, there are strict emissions rules, so that’s going to go to an AV or hybrid profile. And it’s important to think about what that regulatory framework might be and acknowledge the fact that it’s really a mishmash.

There are voluntary guidelines on the federal level right now, but there were no mandates. And so it’s really left up to the cities, counties and states to decide how an AV might be deployed. It’s going to mean probably more lobbyists in DC working with federal folks to ensure that their business doesn’t get hamstrung as a result as well as more of a presence in those cities and states and counties.

But Kate, I’m wondering what is your view from a startup perspective? Do you think of Lyft as a startup anymore are they acting like a startup or are they acting like a company that could handle all of these different complicated, various challenges? I mean, we’ve got pricing pressure, regulatory pressure or you’ve got AV development, opportunities with scooters and all this other stuff. So are they acting like a company that is able to handle this?

Image via Getty Images / Jeff Swensen

Kate: That’s an interesting question. I mean, they’re definitely not a startup anymore by, by anybody’s definition. You maybe could have still used that word, if they were still private, but even then, I know many people would yell at you for using that term for a company worth $15 billion. But now it’s a public company. It’s not a startup. I don’t think they’re acting like a startup, no. I think that they are mature in the way that they’re handling all of these different, so-called paths to profitability.

But we need to wait and see. Let’s see how this year goes, let’s see how they handle all the criticism that they’re going to undoubtedly take from Wall Street or from everyone who’s either interested in buying or just taking a seat and watching how the stock favors and then we’ll know what kind of lessons they took from all those years as a private company. Then we can decide if their behavior is really that of a mature public company.

Kirsten: I do want to make one point that I think is an interesting one on Lyft’s strategy versus Uber is in terms of AVs. Let’s all put a big asterisk that says no, AVs are still a ways out. It is important to note the Lyft and Uber’s strategies for AVs are wildly different and Uber does not take this dual approach. Uber is throwing a ton of capital towards developing their own, self-driving stack and also they’ve done, some acquisitions as well.

They’ve also had quite a bit of trouble. Last year Uber had the first self-driving vehicle fatality that happened in Tempe, Arizona, which looked like it was going to derail their self-driving unit, but it did not. They’re back, testing in a very limited way, but Lyft’s is all about what they call the democratization of autonomous vehicles.

And we can look at that as marketing speech, but I do think that it’s important to look at those words because it shows what their business model is. Their business model is partnerships, alliances, opening up the platform and casting the widest net possible. What I’m very interested to find out is which approach will end up being the winner. It’s going to be a very long game. It’s not going to be anything that’s going to be determined in the next year. I think what Lyft’s proven is that when they look like they’re down and out, they come back.

We’ll see what the better approach is. Do you do everything in-house and launch your own robo-taxi service? Or take capital partners on or do the Lyft approach, with multiple partners? Are partnerships actually too complicated? As someone who covers the startup world, do you have a thought on which one might work or not?

Kate: I have no idea which will work better and I’m sort of excited to see where this all goes, especially as Uber and Lyft are now going to be public.

That’s a good spot to end the call on.

Kirsten: Thanks so much for joining. Thanks again for being Extra Crunch subscribers, we really appreciate it. Bye everyone.

Powered by WPeMatico

Zaver, a Swedish fintech that has built a payments platform to facilitate peer-to-peer trades and more, has picked up just over $1.2 million in seed funding. Backing the burgeoning startup are VC firms Inventure and Inbox Capital, as well as a number of relatively well-established angel investors.

They include Joen Bonnier (partner at Atomico), Tom Dinkelspiel, Pontus Hagnö, Fabian Hielte (owner of Ernström & C:o and a previous investor in Spotify and iZettle), Bo Mattsson (founder of Cint) and Fredrik Österberg (founder of Evolution Gaming).

Aiming to disrupt the market for P2P payment solutions, Zaver is developing a SaaS and accompanying apps to bring together buyers, sellers and merchants with the promise of “secure payments on your terms.” The fintech startup aims to facilitate trades between peers by enabling the use of flexible payment methods such as direct payments, “buy now, pay later” and installments.

To support this, Zaver’s platform claims to embed “intelligent fraud detection” algorithms in tandem with the automatic creation of “verified digital agreements” between transacting parties.

“The Zaver app is the first platform-independent checkout solution for P2P transactions,” says Amir Marandi, who co-founded Zaver alongside Linus Malmén — both former engineering students at KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

“With Zaver’s intelligent fraud prevention, automated and immediate credit decisions and cryptographically signed digital receipts, peers can do safe payments on their own terms with people they really don’t know that well,” he says. “We try to make P2P trades as safe as possible for all parties involved and offer flexible payment options, without compromising on the user experience.”

In addition, Zaver for Business enables merchants to utilise the platform to increase conversion and reduce transaction costs. “Our mission with this product is to reduce the need of a physical card reader,” adds Marandi.

Zaver’s typical user is described as a young student who wants to sell their iPhone on a classified site in a secure way, or a plumber who wants to buy a used VW Golf today and pay later. Meanwhile, the typical customer of Zaver for Business is a company with omni-channel sales, selling products/services online and offline.

“Our main competitors are not the kind of business you might expect,” explains Marandi. “It’s not the banks, but rather upcoming startups wanting to innovate the payment industry. The most direct competitor today I would say is the credit card industry.”

To that end, Zaver makes money from the transaction fees it charges merchants (which it says are up to 70 percent cheaper than traditional payment services), and on interest charged when someone chooses to pay via installments.

Adds Marandi: “Using automated systems for the entire customer journey we are able to offer individualised interest rates at the point of sale. The system automatically chooses an interest rate for you, based on your creditworthiness.”

Powered by WPeMatico

We live in the subscription streaming era of media. Across film, TV, music, and audiobooks, subscription streaming platforms now shape the market. Gaming and podcasting could be next. Where are the startup opportunities in this shift, and in the next shift that will occur?

I sat down with Pär-Jörgen “PJ” Pärson, a partner at European venture firm Northzone, to discuss this at SLUSH this past winter. Pärson – a Swede who now runs Northzone’s office in NYC – led the top early-stage investor in Spotify and led the $35 million Series C in $45/month sports streaming service fuboTV (which has roughly 250,000 subscribers).

In the transcript below, we dive into the core investment thesis that has guided him for 20 years, how he went from running a fish distribution to running a VC firm, his best practices for effective board meetings and VC-entrepreneur relationships, and his assessment of the big social platforms, AR/VR, voice interfaces, blockchain, and the frontier of media. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Eric Peckham:

Northzone isn’t your first VC firm — Back in 1998, you created Cell Ventures, which was more of a holding company or studio model. What was your playbook then?

Powered by WPeMatico

Managed by Q, the office management platform based out of New York, has today been acquired by The We Company, formerly known as WeWork.

Financial terms were not disclosed. The WSJ reports that it was a cash and stock deal. Managed by Q, which has 500 employees, will remain as a wholly owned separate entity and CEO Dan Teran will remain following the acquisition to join WeWork leadership.

Upon its latest financing in January, Managed by Q was valued at $249 million, according to PitchBook.

Here’s what Teran had to say in a prepared statement:

We are excited for this incredible opportunity to deepen our commitment to realizing our ambitious vision of building an operating system for the built world. WeWork is uniquely positioned to invest in workplace technology and services, and I look forward to partnering with their team to build more robust products for our clients and create a global platform to help companies push the bounds on our collective potential.

Managed by Q was founded in 2014 with a plan to change the way that offices run. The platform allowed office managers and other decision-makers to handle supply stocking, cleaning, IT support and other non-work related tasks in the office by simply using the Managed by Q dashboard. Managed by Q serves the demand through a combination of in-house operators and third-party vendors and service providers.

Notably, Managed by Q took a different tack than most other logistics companies, employing their operators as W2 workers instead of 1099 contractors. Moreover, Managed by Q offered a stock option plan to operators that gives 5 percent of the company back to those employees.

The company has raised a total of $128.25 million since launch from investors such as GV, RRE and Kapor Capital. Managed by Q currently serves the markets of New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston and Silicon Valley, with plans to aggressively expand following the acquisition, according to the WSJ.

Not only has Managed by Q swiftly matured into a big player in the NY tech scene and Future of Work space, but it has also fostered interesting competition and consolidation within the space. Managed by Q has itself made several acquisitions, including the purchase of NVS (an office space planning and project management service) and Hivy (an internal comms tool to let employees tell office managers what they need).

Powered by WPeMatico

When everyone always tells you “yes,” you can become a monster. Leaders especially need honest feedback to grow. “If you look at rich people like Donald Trump and you neglect them, you get more Donald Trumps,” says Torch co-founder and CEO Cameron Yarbrough about our gruff president. His app wants to make executive coaching (a polite word for therapy) part of even the busiest executive’s schedule. Torch conducts a 360-degree interview with a client and their employees to assess weaknesses, lays out improvement goals and provides one-on-one video chat sessions with trained counselors.

“Essentially we’re trying to help that person develop the capacity to be a more loving human being in the workplace,” Yarbrough explains. That’s crucial in the age of “hustle porn,” where everyone tries to pretend they’re working all the time and constantly “crushing it.” That can leave leaders facing challenges feeling alone and unworthy. Torch wants to provide a private place to reach out for a helping hand or shoulder to cry on.

Now Torch is ready to lead the way to better management for more companies, as it’s just raised a $10 million Series A round led by Norwest Venture Partners, along with Initialized Capital, Y Combinator and West Ventures. It already has 100 clients, including Reddit and Atrium, but the new cash will fuel its go-to market strategy. Rather than trying to democratize access to coaching, Torch is doubling-down on teaching founders, C-suites and other senior executives how to care… or not care too much.

“I came out of a tough family myself and I had to do a ton of therapy and a ton of meditation to emerge and be an effective leader myself,” Yarbrough recalls. “Philosophically, I care about personal growth. It’s just true all the way down to birth for me. What I’m selling is authentic to who I am.”

Torch’s co-founders met when they were in grad school for counseling psychology degrees, practicing group therapy sessions together. Yarbrough went on to practice clinically and start Well Clinic in the Bay Area, while Keegan Walden got his PhD. Yarbrough worked with married couples to resolve troubles, and “the next thing I know I was working with high-profile startup founders, who like anybody have their fair share of conflicts.”

Torch co-founders (from left): Cameron Yarbrough and Keegan Walden

Coaching romantic partners to be upfront about expectations and kind during arguments translated seamlessly to keep co-founders from buckling under stress. As Yarbrough explains, “I was noticing that they were consistently having problems with five different things:

1. Communication – Surfacing problems early with kindness

2. Healthy workplace boundaries – Making sure people don’t step on each others’ toes

3. How to manage conflict in a healthy way – Staying calm and avoiding finger-pointing

4. How to be positively influential – Being motivational without being annoying or pushy

5. How to manage one’s ego, whether that’s insecurity or narcissism – Seeing the team’s win as the first priority

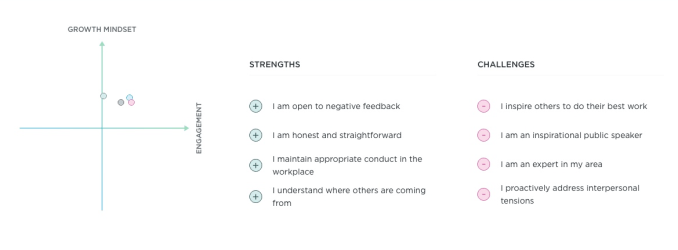

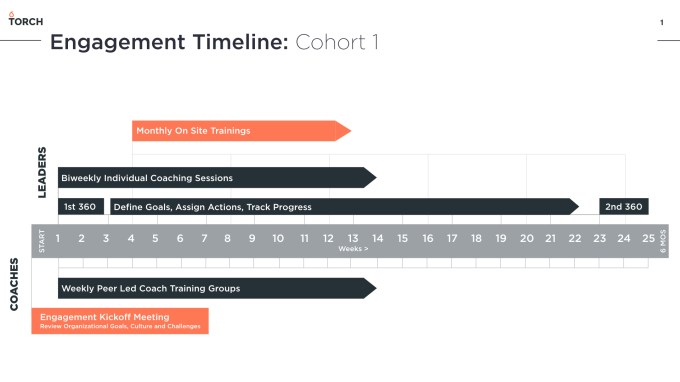

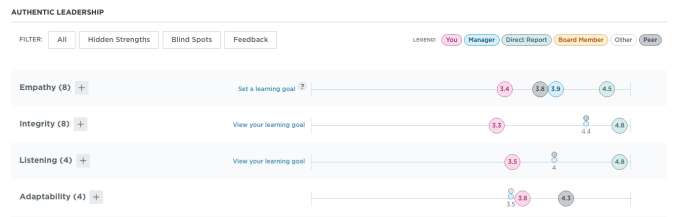

To address those, companies hire Torch to coach one or more of their executives. Torch conducts extensive 360-degree interviews with the exec, as well as their reports, employees and peers. It seeks to score them on empathy, visionary thinking, communication, conflict, management and collaboration, Torch then structures goals and improvement timelines that it tracks with follow-up interviews with the team and quantifiable metrics that can all be tracked by HR through a software dashboard.

To make progress on these fronts, execs do video chat sessions through Torch’s app with coaches trained in these skills. “These are all working people with by nature very tight schedules. They don’t have time to come in for a live session so we come to them in the form of video,” Yarbrough tells me. Rates vary from $500 per month to $1,500 per month for a senior coach in the U.S., Europe, APAC or EMEA, with Torch scoring a significant margin. “We’re B2B only. We’re not focused on being the most affordable solution. We’re focused on being the most effective. And we find that there’s less price sensitivity for senior leaders where the cost of their underperformance is incredibly high to the organization.” Torch’s top source of churn is clients’ going out of business, not ceasing to want its services.

Here are two examples of how big-wigs get better with Torch. “Let’s say we have a client who really just wants to be liked all the time, so much so that they have a hard time getting things done. The feedback from the 360 would come back like ‘I find that Cameron is continually telling me what I want to hear but I don’t know what the expectations are of me and I need him to be more direct,’ ” Yarbrough explains. “The problem is those leaders will eventually fire those people who are failing, but they’ll say they had no idea they weren’t performing because he never told them.” Torch’s coaches can teach them to practice tough-love when necessary and to be more transparent. Meanwhile, a boss who storms around the office and “is super-direct and unkind” could be instructed on how to “develop more empathic attunement.”

Yarbrough specifically designed Torch’s software to not be too prescriptive and leave room for the relationship between the coach and client to unfold. And for privacy, coaches don’t record notes and HR only sees the performance goals and progress, not the content of the video chats. It wants execs to feel comfortable getting real without the worry their personal or trade secrets could leak. “And if someone is bringing in something about trauma or that’s super-sensitive about their personal life, their coach will refer them out to psychotherapists,” Yarbrough assures me.

Torch’s direct competition comes from boutique executive coaching firms around the world, while on the tech side, BetterUp is trying to make coaching scale to every type of employee. But its biggest foe is the stubborn status quo of stiff-upper-lipping it.

The startup world has been plagued by too many tragic suicides, deep depression and paralyzing burnout. It’s easy for founders to judge their own worth not by self-confidence or even the absolute value of their accomplishments, but by their status relative to yesterday. That means one blown deal, employee quitting or product delay can make an executive feel awful. But if they turn to their peers or investors, it could hurt their partnership and fundraising prospects. To keep putting in the work, they need an emotional outlet.

“We ultimately have to create this great software that super-powers human beings. People are not robots yet. They will be someday, but not yet,” Yarbrough concludes with a laugh. IQ alone doesn’t make people succeed. Torch can help them develop the EQ, or emotional intelligence quotient, they need to become a boss that’s looked up to.

Powered by WPeMatico