How to decarbonize America — and the world

Contributor

The Green New Deal has burst onto the American stage, spurring more conversation about – and aspiration for – ambitious climate policy than at any point in at least a decade.

I’m glad to see it. Suddenly, climate is on the agenda, and ambitions for climate policy are higher than perhaps at any point in US history.

The Green New Deal is a resolution right now. It’s a statement of intent. It hasn’t yet progressed to the point of detailed policy proposals or legislation, which means now is the time to help craft its details.

For the last decade I’ve written about and publicly spoken about innovation in clean technology and ways to address climate change. I’ve helped to lead a climate-fighting citizen ballot initiative in my home state of Washington, invested in clean energy startups, and advised on climate and clean energy policies of other nations.

In that time, my views on what sort of climate policies have the most impact and have the greatest chances of winning over voters have changed. Policies that I thought were foolish a decade ago have revealed themselves to have been farsighted and effective. Policies I thought were powerful and elegant have, on closer inspection, revealed themselves to be far less effective than I believed. And the history of climate and energy legislation and attitudes in the US has demonstrated a path to getting new and more ambitious policies passed.

What I’ve learned over time is that good climate policy has 3 key traits:

- It has a large, meaningful impact on carbon emissions and climate change.

- It specifically tackles the problems that aren’t already being tackled by the market.

- It actually gets passed into law.

All of that is compatible with a Green New Deal. Here’s what it could look like.

- Impact: Climate Change Isn’t Local. Good Policy Isn’t, Either.

The conventional wisdom on climate policy is straightforward. Every nation uses its policies to reduce its own emissions. This conventional wisdom is wrong. Carbon dioxide doesn’t honor national boundaries. Climate change is global. And the best climate policies have a global impact as well.

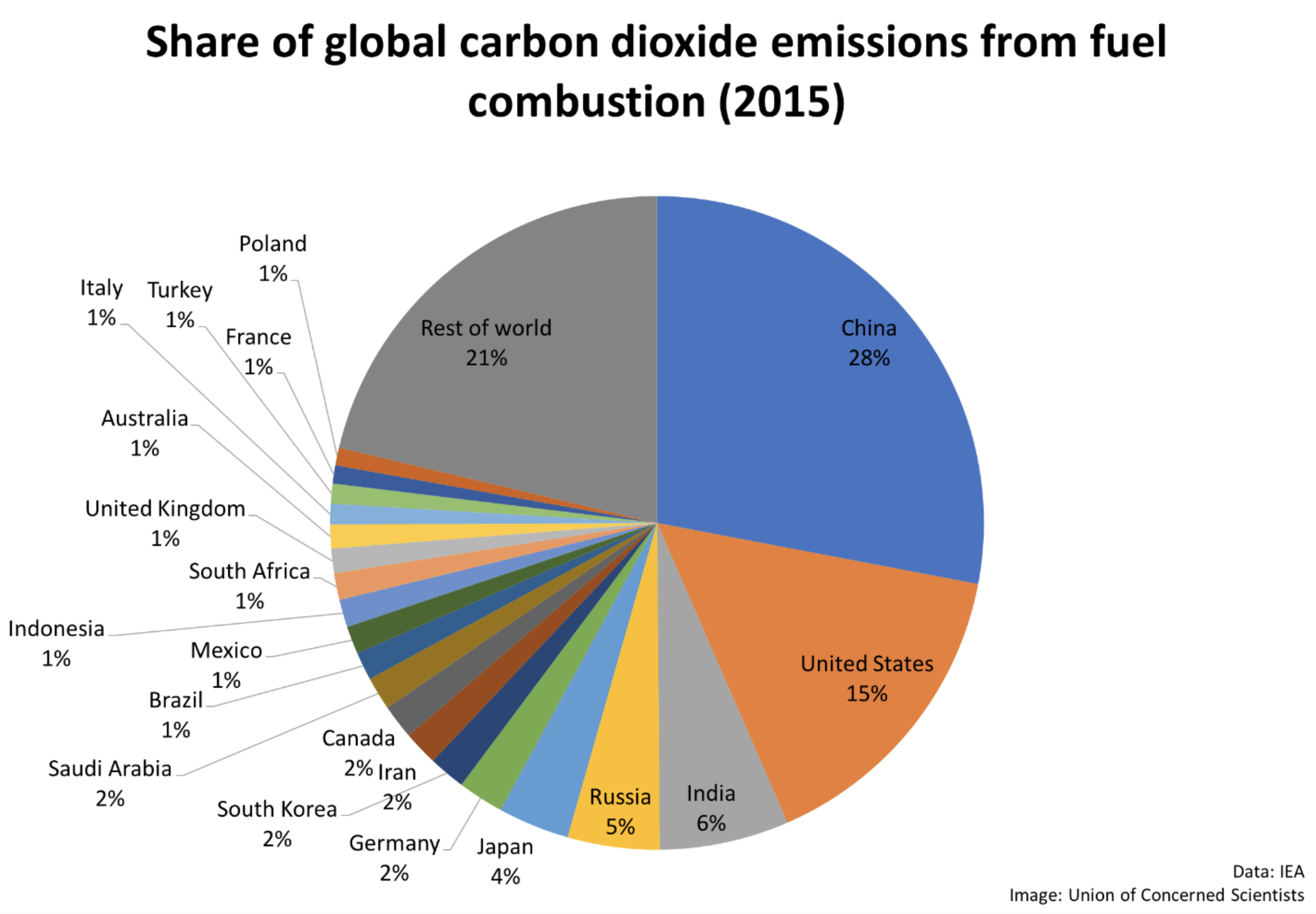

The US, overwhelmingly, is the country most responsible for climate change. The carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases we’ve emitted over the past decades are largely still in the atmosphere, still warming the planet. The world’s present and future emissions, though, are increasingly elsewhere. The US now accounts for just 15% of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels. And because the developing world is rising in energy consumption far faster than the US, American emissions will be an ever-smaller share each year.

That means that, despite the fact that the US is the largest overall contributor to climate change thus far, the US could completely eliminate its carbon emissions and barely affect the future course of climate.

This means we need a different strategy. It’s not enough to eliminate the US’s carbon emissions alone. Our goal has to be to drive down the whole world’s emissions.

The Most Effective Climate Policy in the World

How can the US drive down the emissions of other countries? We can do it by making clean technologies irresistible to the entire world. And there we can take a lesson from the most effective climate policy of all time – Germany’s early subsidies of solar and wind.

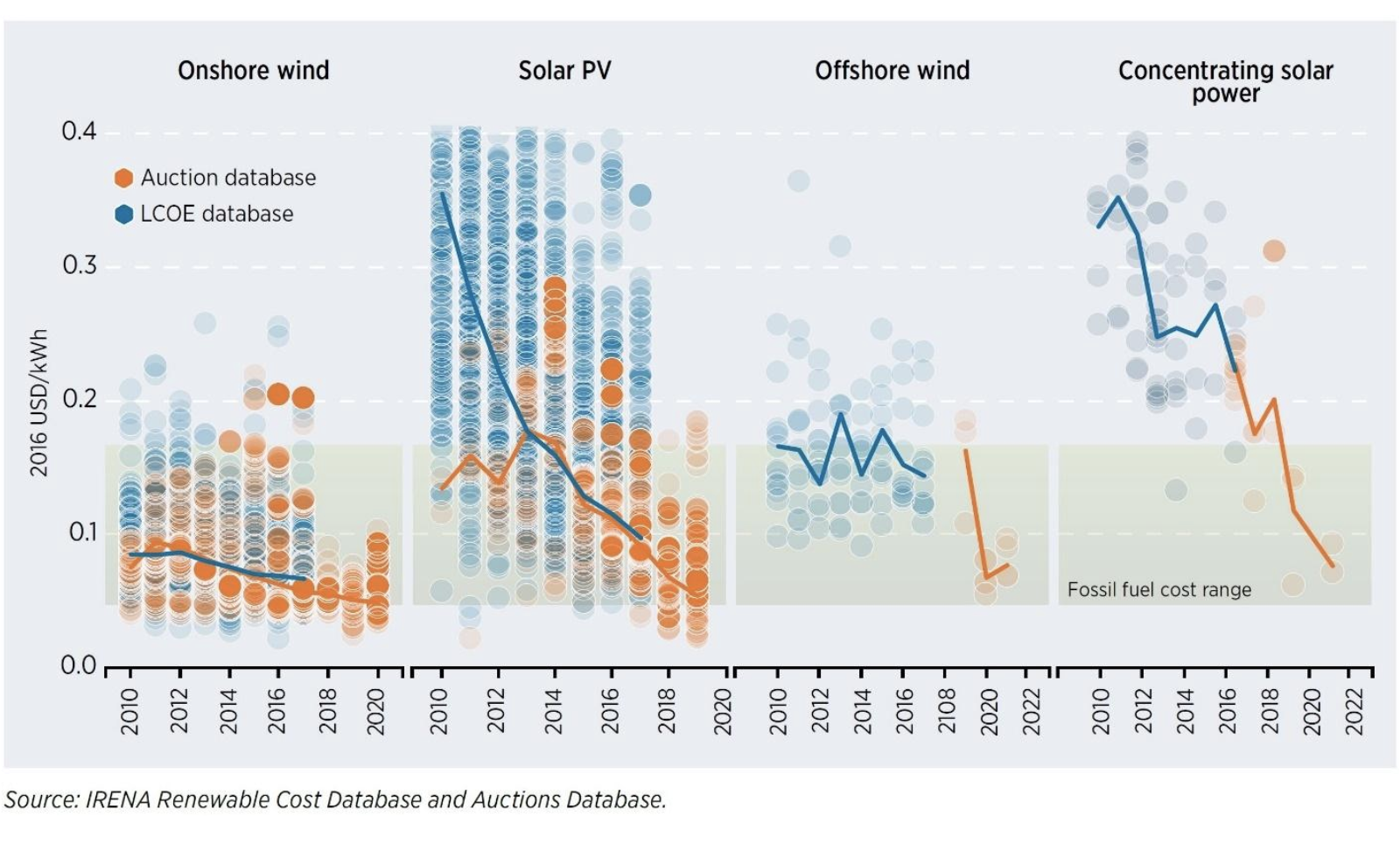

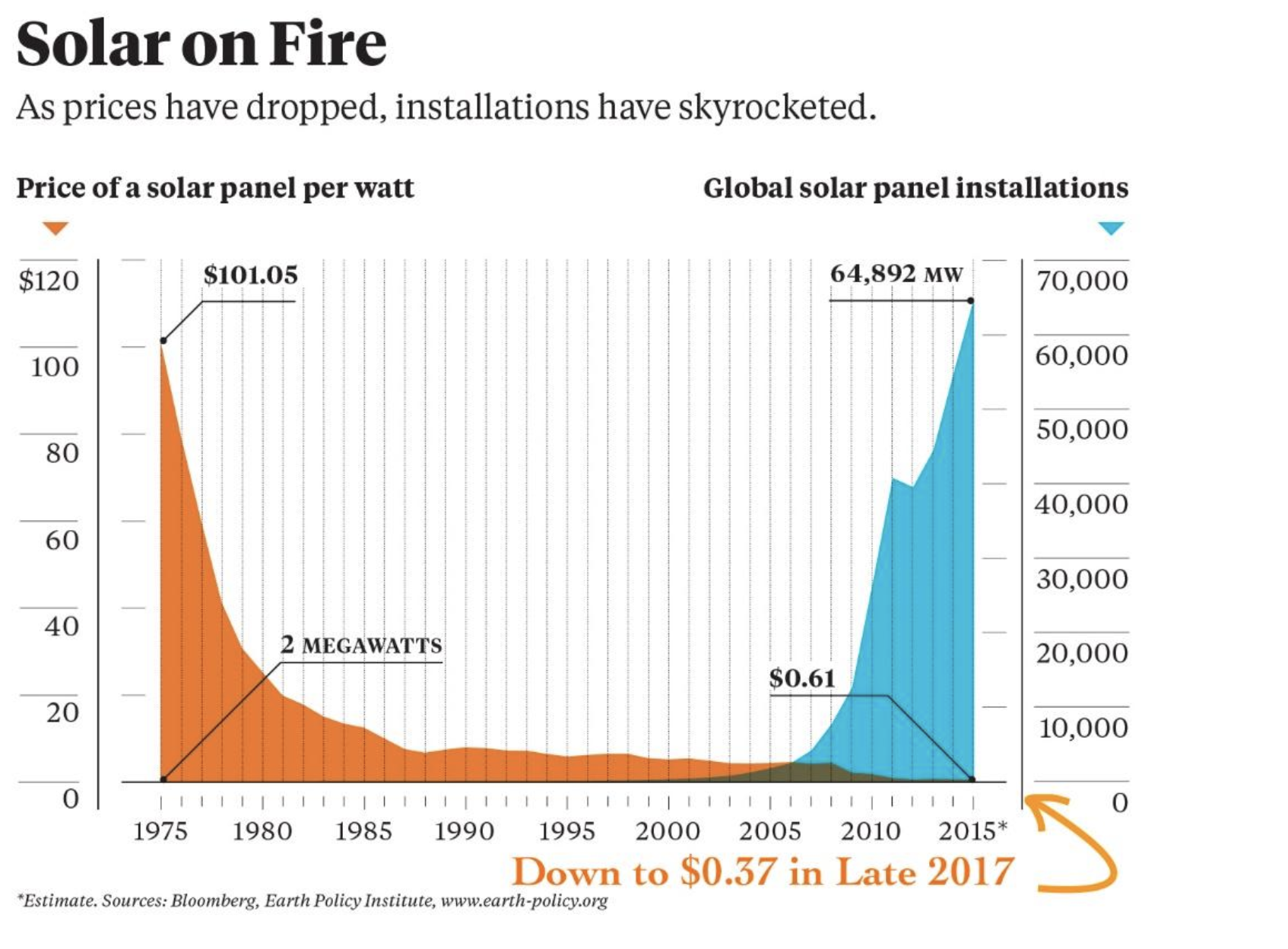

Solar panels and electricity-producing wind farms have been around for decades. Yet, for most of that time, they’ve been a far more expensive way to produce electricity than burning coal or natural gas. Germany changed that. Starting in 2010, Germany’s Energiewende legislation heavily subsidized solar and wind. That, in turn, drove utilities and home owners and corporations to purchase solar and wind. And that, in turn, made the technology cheaper. As prices fell, other nations – first European nations, then the US, and then China – jumped into the fray, enacting more ambitious policies that further brought down the price of solar and wind (and now batteries and electric cars).

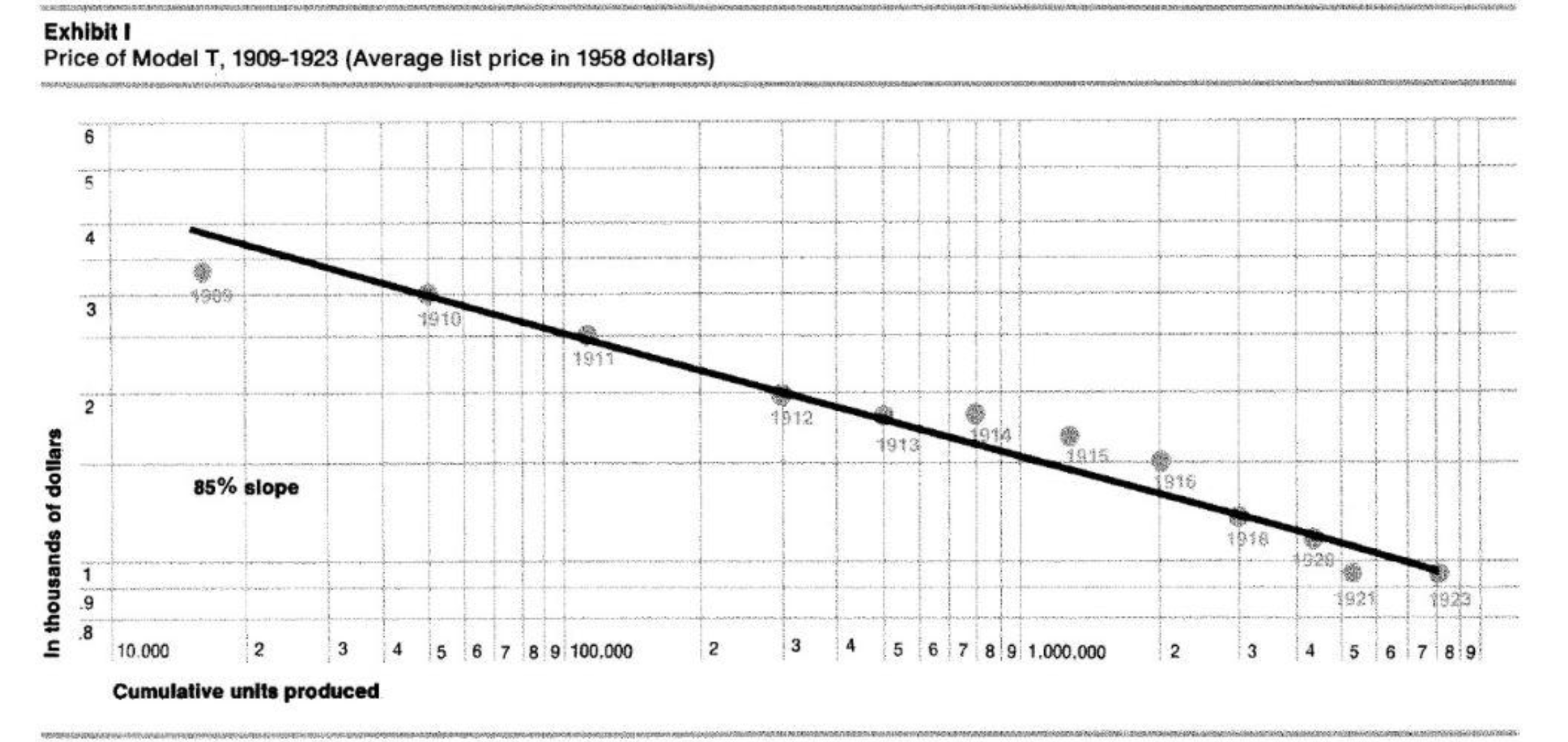

Why did subsidies bring down the price of technology? Because industry scale leads to industry learning and innovation, and that, in turn, leads to lower cost ways to manufacture, deploy, and manage new technologies. We’ve seen this for a century. Almost all technologies improve via Wright’s Law, often referred to as the learning curve or the experience curve. In the late 1930s, Theodore Paul Wright, an aeronautical engineer, observed that every doubling of production of US aircraft brought down prices by 13%. Since then, a similar effect has been found in nearly every technology area, going back to the Ford Model T.

Electricity from solar power, meanwhile, drops in cost by 25-30% for every doubling in scale. Battery costs drop around 20-30% per doubling of scale. Wind power costs drop by 15-20% for every doubling. Scale leads to learning, and learning leads to lower costs.

Germany began subsidizing solar and wind when they were extremely small scale industries, and their costs were quite high. Those subsidies drove German utilities, businesses, and home owners to purchase clean energy. That created a market. That, in turn, led solar and wind manufacturers to leap into the market, competing ruthlessly against one another to bring down their prices faster, offering the best product at the best price to customers.

By scaling the clean energy industries, Germany lowered the price of solar and wind for everyone, worldwide, forever.

The International Renewable Energy Agency finds that, between 2010 and 2019, the price of solar power, worldwide, has dropped by more than a factor of 5. The price of offshore wind power has dropped by a factor of three.

In just the past decade, solar power has gone from being uneconomical anywhere on earth without subsidies, to being cheaper than any fossil fuel electricity in the sunniest parts of the world. Building new solar is now cheaper than building new fossil fuel electricity plants in India, Chile, Mexico, Spain, and in sunny US states like Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, and Texas.

And because, in general, businesses, utilities, and consumers all around the world will deploy the cheapest energy they can, solar is now the fastest growing energy source around the world.

Happy? Good. Thank policy makers in Germany, and the US, and China – all of whom took action to bootstrap markets for solar and wind before they were cost-competitive.

The lesson for US climate policy is clear: The biggest impact we can have is by driving down the cost of technologies that reduce carbon emissions, to the point that clean technologies are cheapest way to provide the energy, food, and transportation that everyone around the world desires, and then spreading those technologies to the world. That means a mix of early-stage government R&D, government incentives to scale deployment in the private sector, and a very healthy dollop of private sector competition.

1 – As solar volume has grown, prices have dropped, leading to more growth.

Would the Green New Deal drive down the cost of clean technologies in a way that scales to the rest of the world? The current resolution is vague on exactly how the rapid decarbonization in the US would happen. One reason for concern is that the now-retracted Green New Deal FAQ released by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez specifically dismissed the idea that the private sector – even with government incentives – could pull off this decarbonization, and explicitly says that “Merely incentivizing the private sector doesn’t work”.

I agree in one sense – basic government R&D is a high-value investment, especially when the technologies we need to invent don’t even exist yet. The government has a vital role to play. At the same time, the incredible, unprecedented decline in cost of solar power, wind power, batteries, and electric cars has happened both because of early government R&D, and because private sector companies, incentivized by governments, have brought these technologies to market and been forced to compete with one another to provide the best technology at the lowest price. Ignoring this is to ignore what brought us the very best progress we’ve seen in cleaning up the way we produce energy.

The FAQ I reference has been retracted. The Green New Deal hasn’t yet become a detailed roadmap or legislation. As it does, I urge you, Green New Deal legislators and architects: Craft policies that create incentives to build and deploy clean technologies. Then use the market for what it’s good at: fierce competition that delivers ever-better products at ever-lower prices.

- Tackling the Hardest, Least-Solved Problems

The Green New Deal resolution is really quite comprehensive. It touches on almost every source of US emissions.

Even so, there’s a tendency for climate and energy wonks – and legislators – to focus on electricity and cars when discussing climate policy.

Electricity and cars aren’t our hardest problems. They’re both big chunks of our carbon emissions, yes. And they both need more policy to drive them home. (More on that down below.) They’re also the areas where we’ve made the most progress, with incredible declines in the price of clean electricity and electric vehicles that put us at the edge of a tipping point. We aren’t over the hump yet, but the solutions are here – and if we continue to push them with policy, we can decarbonize electricity and cars.

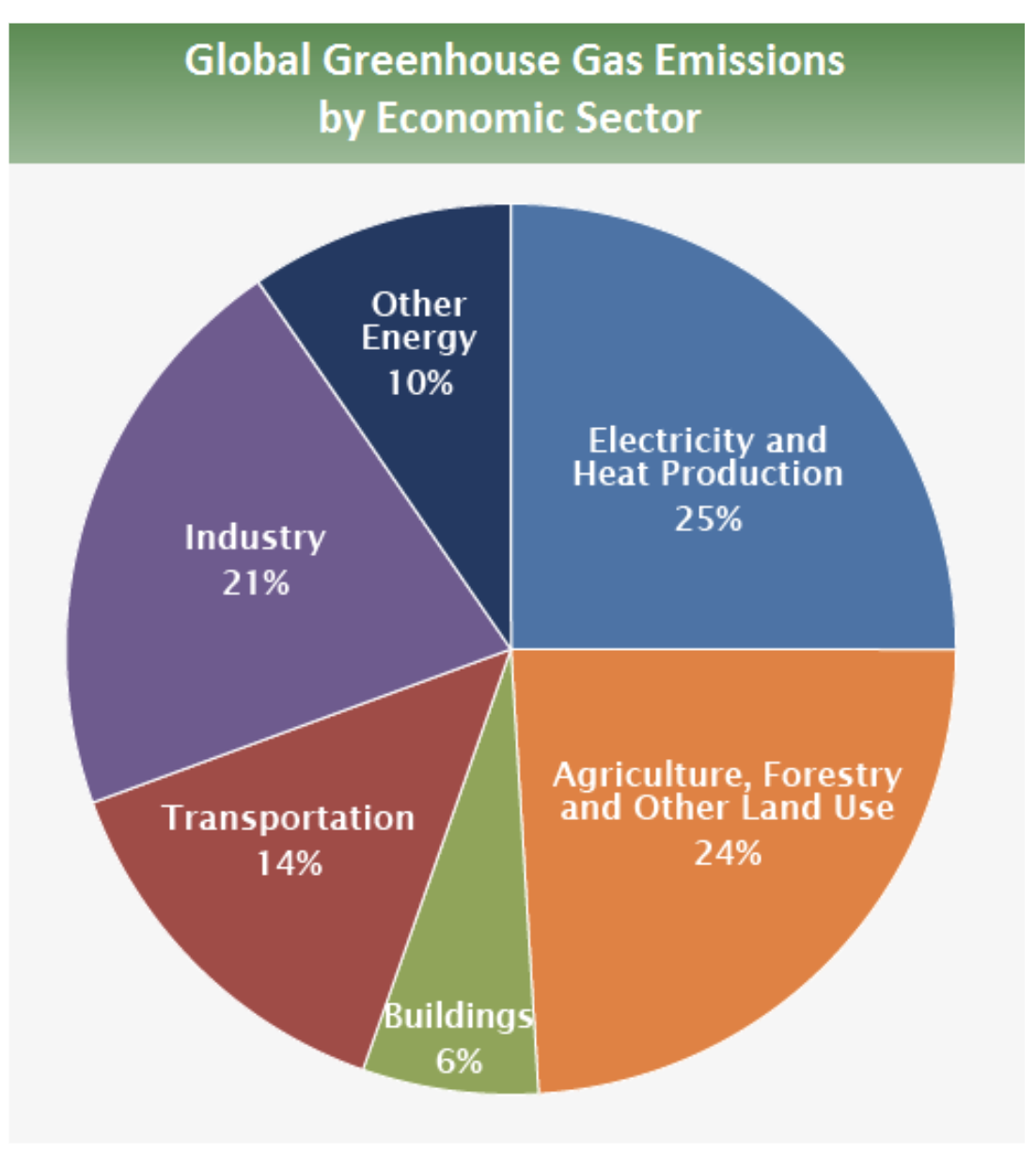

Our hardest climate problems – the ones that are both large and lack obvious solutions – are agriculture (and deforestation – its major side effect) and industry. Together these are 45% of global carbon emissions. And solutions are scarce.

Our hardest climate problems – the ones that are both large and lack obvious solutions – are agriculture (and deforestation – its major side effect) and industry. Together these are 45% of global carbon emissions. And solutions are scarce.

Agriculture and land use account for 24% of all human emissions. That’s nearly as much as electricity, and twice as much all the world’s passenger cars combined.

Industry – steel, cement, and manufacturing – account for 21% of human emissions – one and a half times as much as all the world’s cars, trucks, ships, trains, and planes combined.

Add industry, agriculture, and land use together and you have a very sticky, very difficult-to-improve 45% of carbon emissions.

By contrast, electricity and transportation are 39% of global emissions – nearly as big. The good news is that in electricity and transportation, we have momentum.

We do NOT have momentum in reducing the carbon emissions of industry and agriculture.

Decarbonizing Agriculture and Industry

The Green New Deal does, happily, mention these sectors. In agriculture, though, it avoids the biggest chunk of the problem: Livestock.

Livestock around the world – specifically cows, pigs, and other mammals – consume a tremendous amount of the world’s agriculture output. They drive the bulk of the deforestation around the world (which itself releases carbon into the atmosphere, and reduces forest land that could absorb carbon instead). And cows and pigs belch methane – a greenhouse gas that’s causes tremendously more warming than CO2 – about 100 times more in the first year, and 30 times more over the course of a century. Livestock in total produce about 15% of the world’s carbon emissions, as much as all transportation on land, air, and sea combined.

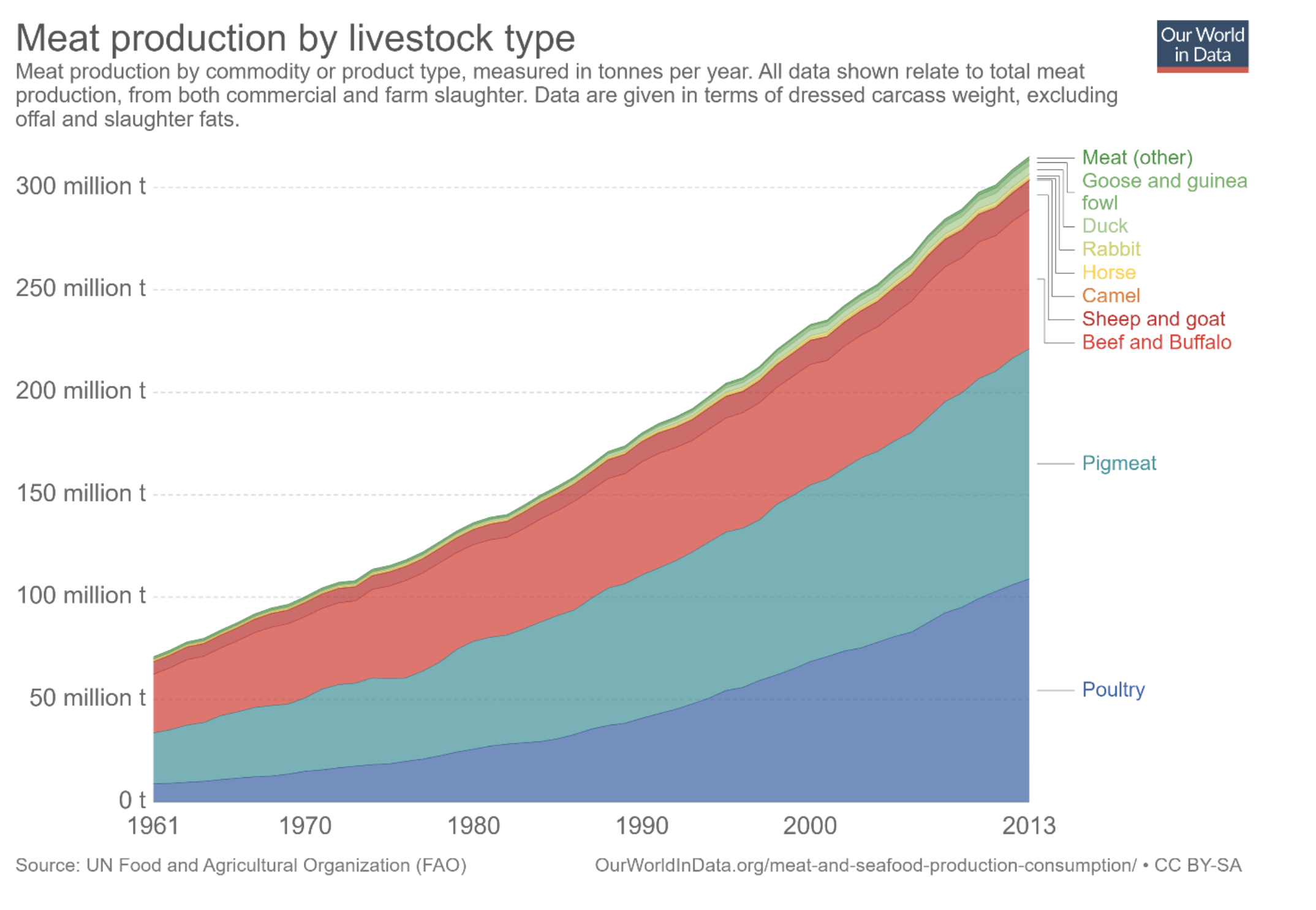

And the world’s appetite for meat is rapidly growing, with consumption expected to double in the next 40 or so years.

Cows should scare you more than coal.

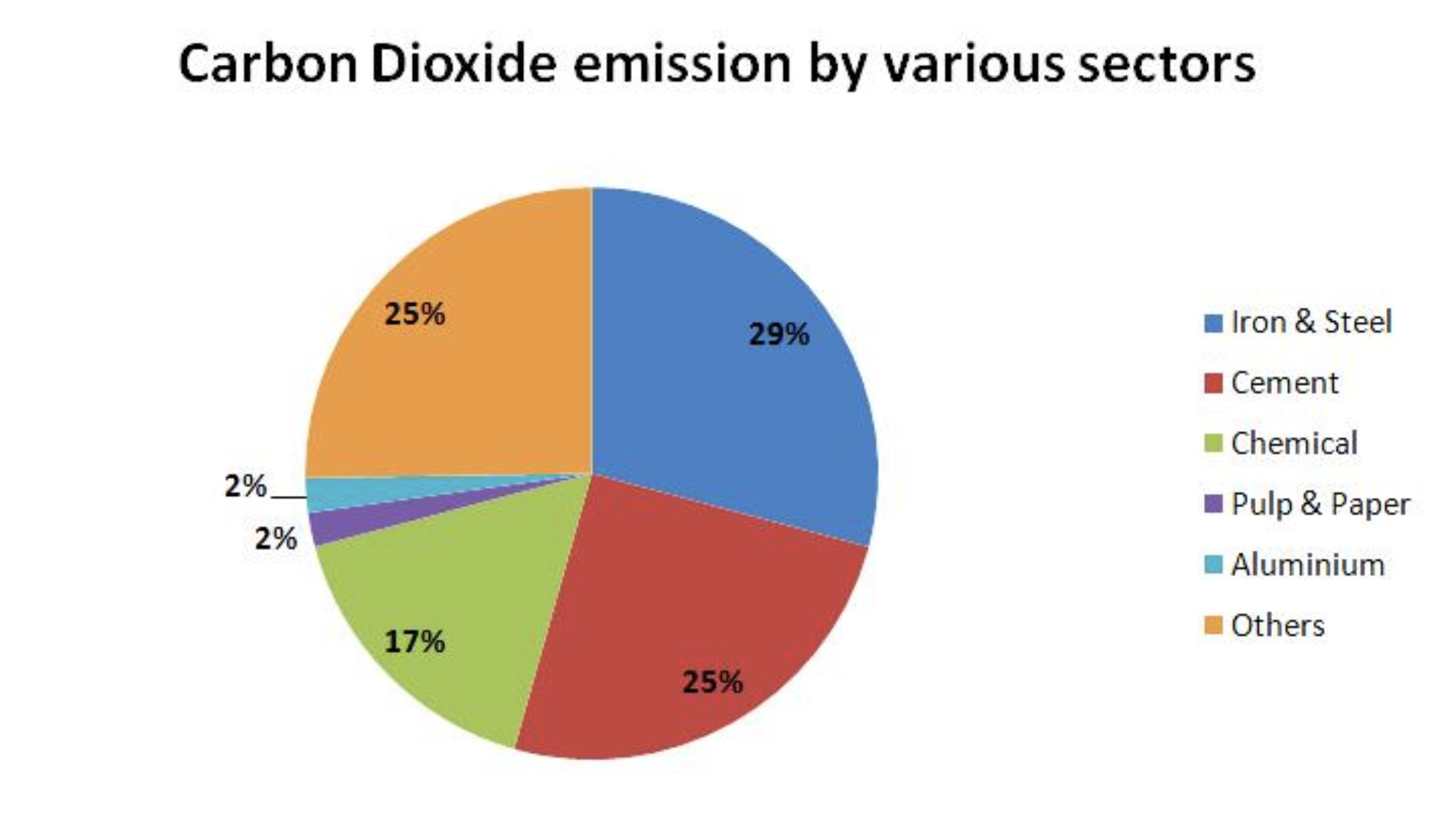

In industry, meanwhile, steel and cement production both remain incredibly carbon intensive. We’ve learned to recycle steel using electricity, but making new steel from ore still involves the use of a tremendous amount of coal. (Theoretical ways to make steel without coal exist, but aren’t expected to be commercially viable for another 20 years.) We’re closer to technologies that could make cement without carbon emissions, but those technologies are still young, expensive, and haven’t been deployed to any significant degree. And the rest of industry – from manufacturing finished goods to making petrochemical products like plastics and lubricants – remains extremely carbon intensive.

These two sectors – agriculture and industry – are on path to be the two largest sources of carbon emissions in the world. And they’re the ones we have the fewest and least developed solutions for. The Green New Deal – or any serious climate policy – ought to focus first and foremost on R&D to develop methods for clean agriculture and clean construction and manufacturing; and then on incentives to deploy those clean methods, which will initially be extremely expensive, until they hit the scale to compete directly with dirty methods on cost alone.

What would a climate policy for agriculture and industry look like? Let’s take a page from energy, where we have a one-two punch: 1) Agencies like the Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency for Energy, ARPA-E, that funds early stage energy science and technology R&D; and 2) A breadth of state and national subsidies and incentives that help those technologies reach higher scale and lower costs.

This one-two punch first invents technology (ARPA-E is modeled after the original ARPA, which created the foundations of the internet, originally called ARPANET), and then scales technology to the point that the new clean technology is cheaper than the alternatives.

We can use that one-two punch in agriculture and industry, by creating:

- An ARPA-A in the Department of Agriculture, tasked with finding a way to reduce the carbon emissions of agriculture broadly, and especially of livestock and meat. ARPA-A might fund research into:

- Radically increasing crop yields so farmers have less need to chop down forests to feed their animals.

- Technologies to eliminate the methane emissions of cows and pigs.

- Technologies to reduce the emissions of NOx (another incredibly powerful greenhouse gas) that’s produced by animal manure left on fields, and to a lesser extent by excess synthetic fertilizer.

- Real-time global deforestation monitoring technology, (perhaps in partnership with other agencies) to spot illegal deforestation as soon as it happens, and nip it in the bud.

- New alternatives to meat – from plants or stem cells – that might someday taste and feel as compelling as the real thing.

- Incentives to Deploy Clean Agriculture would be paired with the early-stage research of an ARPA-A. Just-out-of-the-lab technologies to reduce agricultural greenhouse emissions are likely to start expensive. Early (and steep) subsidies could motivate farmers (or even consumers) to adopt those new technologies and products. Just like German subsidies, by scaling solar, bootstrapped an industry whose fierce competition then brought down prices, early subsidies for clean agriculture and clean foods would do the same.

Such incentives could include:- Incentives for farmers who capture carbon in their soils. (By far the cheapest way to remove carbon from the atmosphere.)

- Subsidizing feed additives or other products that reduce methane emissions or NOx emissions from animals and their manure.

- Tax breaks for farmers who invest in “precision agriculture” technologies that reduce the amount of fertilizer or fuel they use on the farm.

- Incentives for farmers to deploy clean energy on their farms, and to switch farm operations from diesel to electric.

- An ARPA-I for Industry, meanwhile, would be chartered with funding early stage R&D in carbon-free industry. Research areas would include:

- Carbon-free steel – technologies that can make steel from iron ore without the use of coal.

- Carbon-free cement technologies.

- Alternative building materials that have lower carbon emissions.

- Carbon-free manufacturing technologies.

- Better carbon-free or low-carbon plastics, lubricants, and other petrochemicals that don’t require oil extraction.

In several of these areas some options exist today, but a need for more innovation and more fundamental research – that the federal government is uniquely equipped to fund – still exists.

2-ARPA-I would fund research to decarbonize industry, starting with the largest industrial sources – steel, cement, and petrochemicals.

- Incentives to Deploy Carbon-Free Industrial Methods would give steel mills, manufacturers, and builders a reason to use these new, carbon-free methods while they’re still young and expensive. These incentives would include:

- Tax breaks for new carbon-free industrial equipment, to reduce the cost for manufacturers to adopt these new technologies in their early stages.

- Tax breaks or subsidies for the buyers of carbon-free steel, cement, or other industrial goods, to bootstrap a market of customers for these new products and grow it to scale.

As with solar and wind in Germany, scaling use of these methods in industry would bring their prices down, with a target of beating the price of existing, carbon-heavy methods.

All of the above is compatible with Green New Deal language. It’s just a matter of emphasis. We need to double down on these two areas – agriculture and industry – that are soon to be the largest sources of global carbon emissions, and the ones we have the least progress in solving.

- Good Policy Must be Passable

Perhaps the most important question about the Green New Deal is this – what can we actually pass?

The Green New Deal has already moved the Overton window, by elevating the conversation about climate. At the state level, in progressive states like California and New York, Democrats have solid majorities and could pass large parts of the Green New Deal that are applicable at a state level. As I argued just after Donald Trump’s election, the States are where we can most effectively push for climate action.

What about at the Federal level? Maybe the Green New Deal, by motivating the base, will lead to more electoral victories for Democrats in 2020. Or maybe it will hurt in red states like Alabama, where Democrats are defending a Senate seat. It’s far too early to say.

Democrats don’t have any chance of reaching 60 Senate seats in 2020. They do have the option, if they win a majority and the Presidency, of eliminating the legislative filibuster (using the so-called “nuclear option”), in which case a simple majority of the House and Senate could pass as much of the Green New Deal as Democrats could achieve consensus on, without the need for any Republican legislators.

What if none of the above occurs? What if Democrats don’t get a Senate majority at all? Or do get a majority, but are unwilling to eliminate the legislative filibuster? Could any parts of the Green New Deal pass with some Republican support?

Bipartisan Climate Policy is Possible. In Fact, It’s Here Now

Yes. Recent history shows that, while climate is a highly divisive issue in the US, clean energy and innovation have massive support on both sides of the aisle.

Consider the following:

- In 2015, a Republican Congress reached a bipartisan deal to extend the solar and wind tax credits (the ITC and PTC) out through 2022.

- In 2017, a Republican Congress, under Donald Trump, could have easily repealed or prematurely ended these tax credits. Yet the GOP left solar, wind, and electric vehicle tax credits untouched.

- In 2017, a Republican Congress gave clean energy research in the Department of Energy’s ARPA-E its largest budget increase since 2009.

Wait. Don’t Republicans hate clean energy?

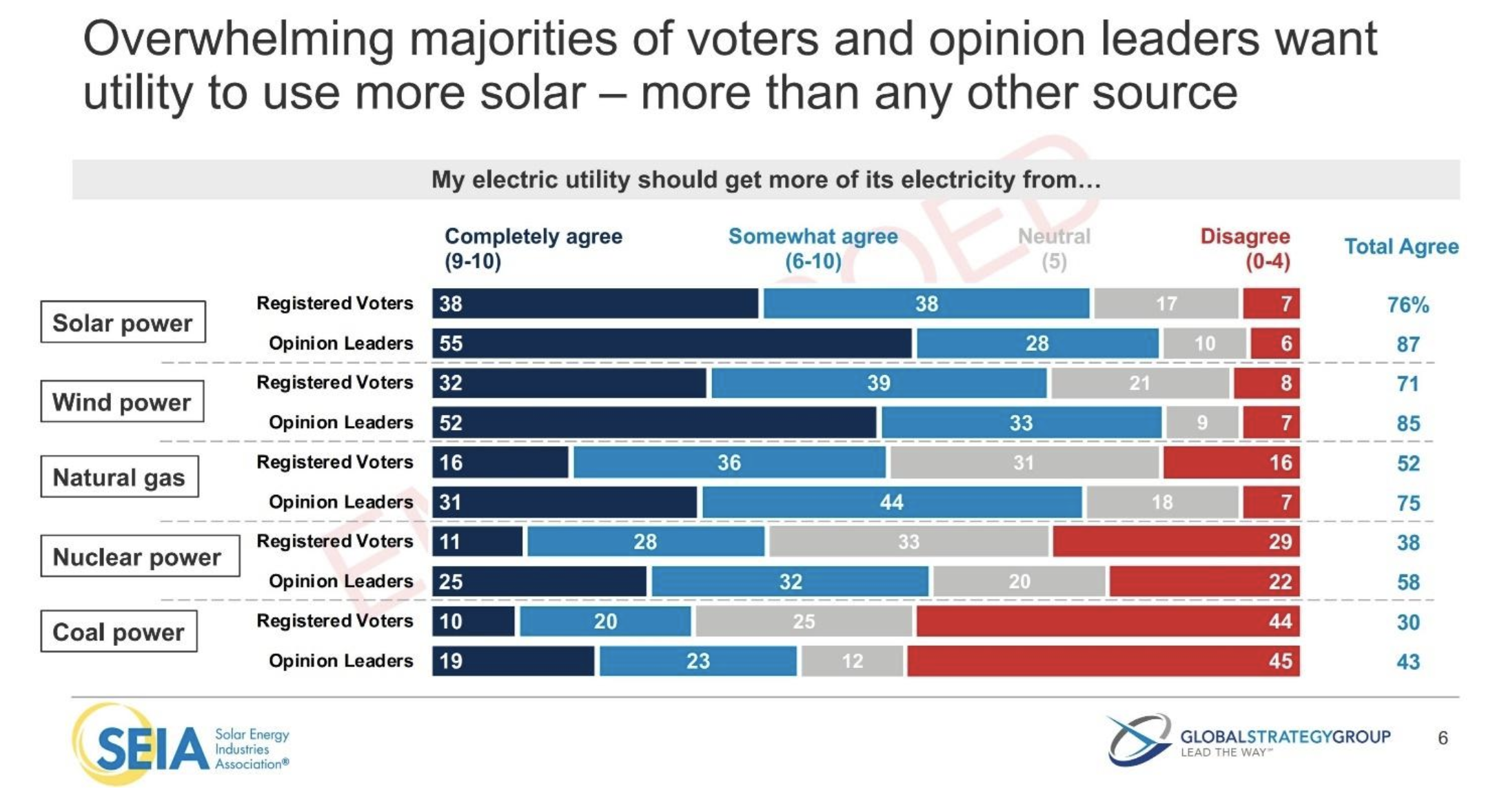

Nope. Not at all. Americans on both sides of the aisle love solar and wind. Solar is the most popular energy source in the US, with 76% of Americans saying that their utility should get more energy from solar. Wind is a close second, at 71%. The third choice, natural gas, is 24 points behind solar, at 52%. And a meager 30% of Americans want more coal.

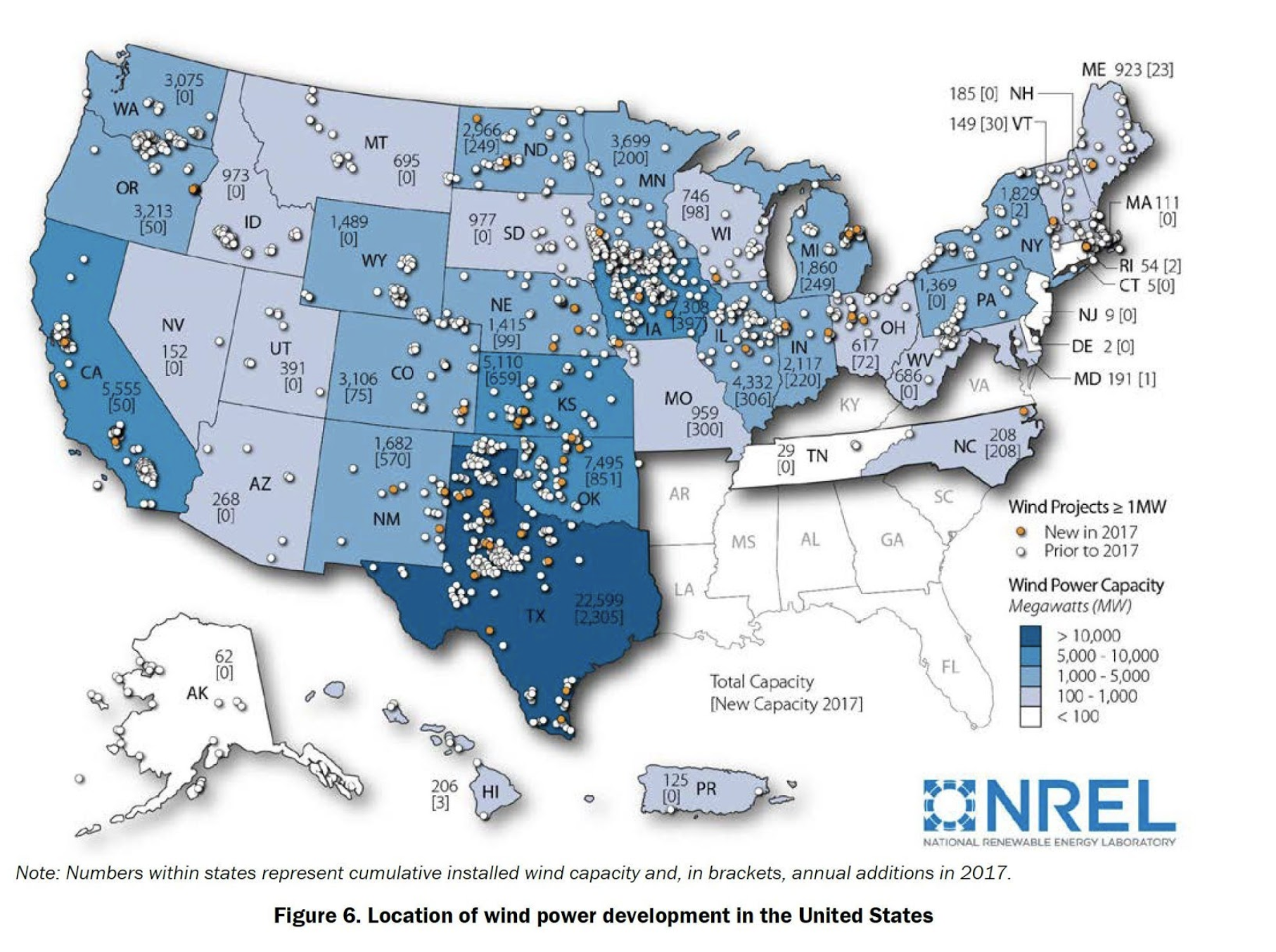

It helps that clean energy is literally everywhere in America. Solar and wind have been built out in every state. Wind power, especially, is booming in rural districts in red states. Representatives from these districts, and Republican Senators from red states like Iowa and Texas that have deployed a tremendous amount of solar and wind, have every reason to support policies that benefit clean energy.

What’s more, Americans – on both sides of the aisle – wildly support research into new technologies that can improve their lives. A whopping 85% of Americans support funding more research into renewable energy sources. Ready for the real shocker? Solid majorities in virtually every county and every congressional district in the US support more funding of research into clean energy.

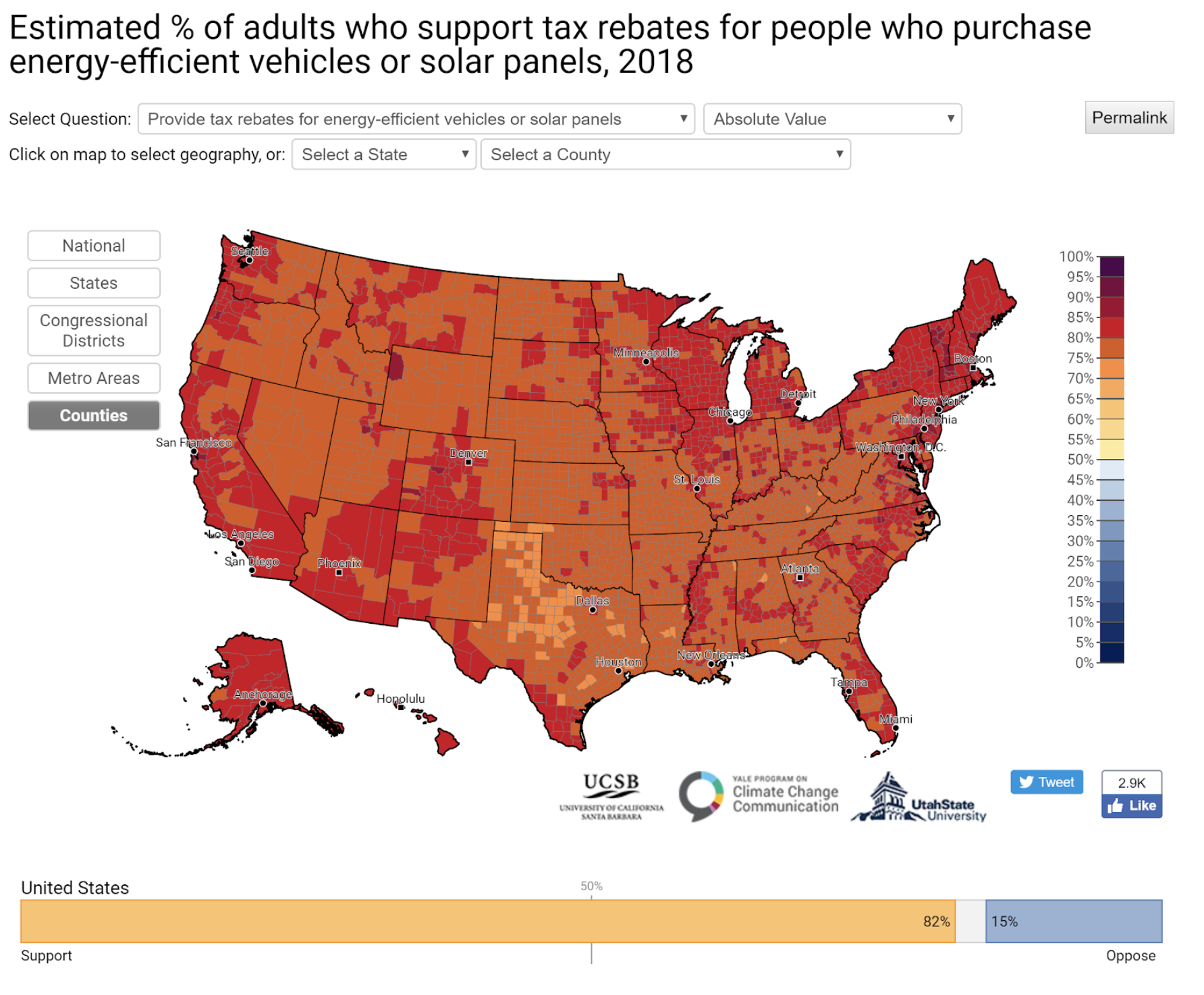

Nearly as many Americans – 82% – support tax breaks for Americans who purchase energy-efficient vehicles or solar panels. And again, the support isn’t limited to blue states or blue districts. It’s overwhelmingly national.

So Americans don’t just love innovation and R&D spending. They also support incentives to deploy clean technology faster. And, in fact, those two policy levers – more research funding, and incentives to deploy clean technology – get both the most support in poll after poll, the most bipartisan support, and the most geographically consistent support. If you want a policy proposal that that will work in red or purple states, or that can win over some Republican Senators and Representatives, clean technology research and clean technology deployment incentives are the two most likely to garner support.

What Bipartisan Policy Would Look Like

If Democrats do get both the White House a filibuster-proof congressional majority – one way or another – and get enough internal consensus, they can drive forward whatever GND policy they wish. Right now, that seems unlikely to me.

In the event that we have a Congress without that filibuster-proof majority, or with enough moderate democrats who balk at the entirety of the Green New Deal, there are still extremely effective climate policies that Congress can put in place.

First, in industry and agriculture, the four policies we mentioned already:

- ARPA-A to fund research into carbon-free agriculture & forestry.

- Clean Agriculture Incentives and subsidies to deploy carbon-free ag rapidly to farmers and drive down its price through scale.

- ARPA-I to fund research into carbon-free steel, cement, and manufacturing.

- Clean Industry Incentives and subsidies to deploy carbon-free industrial tech and drive it down in price.

Those policies in agriculture and industry have an excellent chance of getting bipartisan support. They follow a pattern of Americans being willing to invest in new science and technology R&D. And, because they benefit industrial and agricultural states and districts, by giving carrots for deploying clean industry and clean agriculture, they’re a benefit to politicians from those – often red – states that have the greatest concentration of farms and factories. That’s the exact opposite of a policy that penalized farmers or factories for their carbon emissions. You’d have a hard time getting much bipartisan support for that. Make the policy an incentive that helps farms and industry thrive, and helps them get an edge over their global competitors, and the politics completely change.

In electricity, transportation, and buildings, there are also policies – some of them counter-intuitive – that would accelerate us towards a clean future :

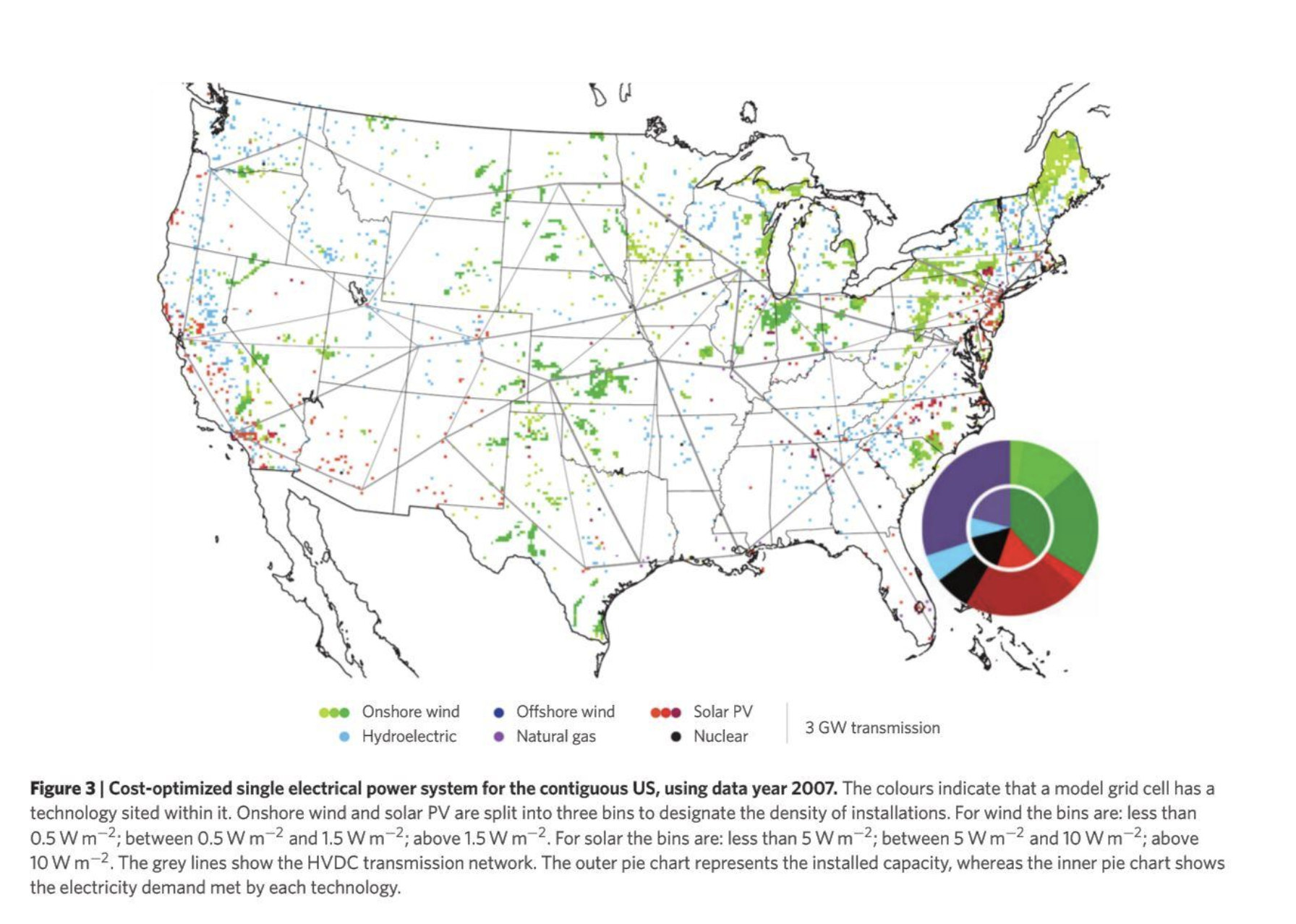

- Continent-Wide Electricity Transmission. It’s a common perception that renewable energy means less dependence on the grid. The opposite is true, for two reasons. First, at any given time, weather may hurt the output of solar panels or wind farms in any given area. The further away you are from that area, the less likely you are to be in the same weather pattern. Second, the sunniest parts of the US, the windiest parts of the US, and the parts of the US that need the most electricity don’t all coincide. Study after study shows that the larger an area we integrate renewables over, the more renewables we can put on the grid, and the lower the cost.

3- A nation-sized grid increases the amount of energy we can use from solar and wind, and reduces the overall cost. Source – Nature Climate Change

Long-range transmission is also remarkably efficient and low cost. High-voltage DC transmission lines can send power 2,000 miles with only 10% losses and a small additional cost. That means solar power plants in Texas could be powering New York City…an hour after the sun has gone down in New York. China understands this, and is building the world’s largest high voltage power grid, moving power from the sunniest and windiest areas in the west to the coastal population centers 3,000 km (1,860 miles) east. In the US, meanwhile, it’s nearly impossible to build new long-range transmission – largely because of NIMBY. Congress should make it easier to get the necessary permissions to build transmission, paving the way for a grid with more and cheaper clean energy.

4- China’s Ultra High Voltage Grid moves clean energy 2,000 miles from the sunny and windy interior to the population centers on the eastern coast. The US has nothing similar.

- Clear the Way for Offshore Wind. The most exciting development in wind power is building offshore. Winds blow faster and more consistently just a few miles off the coast of the US than they do almost anywhere on land. Not only does that mean offshore wind power is likely to be the cheapest wind power, it also means – because the winds are more steady – that it causes fewer intermittency problems for grid operators and is closer to being a “baseload”-like power source. Offshore wind sites are also closer to electricity demand in cities along the coast, making it easier to get power where its needed. And while solar power peaks in the sunny months of summer, wind power peaks in winter – making solar and wind great complements for each other. Offshore wind has plunged in price in Europe, reaching grid parity last summer, and is now growing faster there than wind power on land. It’s also still much smaller than on-land wind. That means that is has much farther to fall in price, and that deploying it now can bring the price down faster than with on-land wind. Unfortunately, the US is far behind in building offshore wind. A law from the 1920s and a raft of lawsuits have held offshore wind power up. Congress can and should take action to clear the way for offshore wind.

- Extend & Unify Solar, Wind, and Energy Storage Tax Incentives. Congress should make the 30% Investment Tax Credit for solar (the ITC) permanent. Failing that, it should extend it out to at least 2030. Wind, which has long mostly used a different tax credit called the PTC, should be moved to the same 30% tax credit and timing as solar. Energy storage – batteries and the technologies that come after them – should get the exact same tax credit, however and wherever that energy storage technology is deployed. While this tax credit may sound modest, solar and wind are now on the very edge of a tipping point.

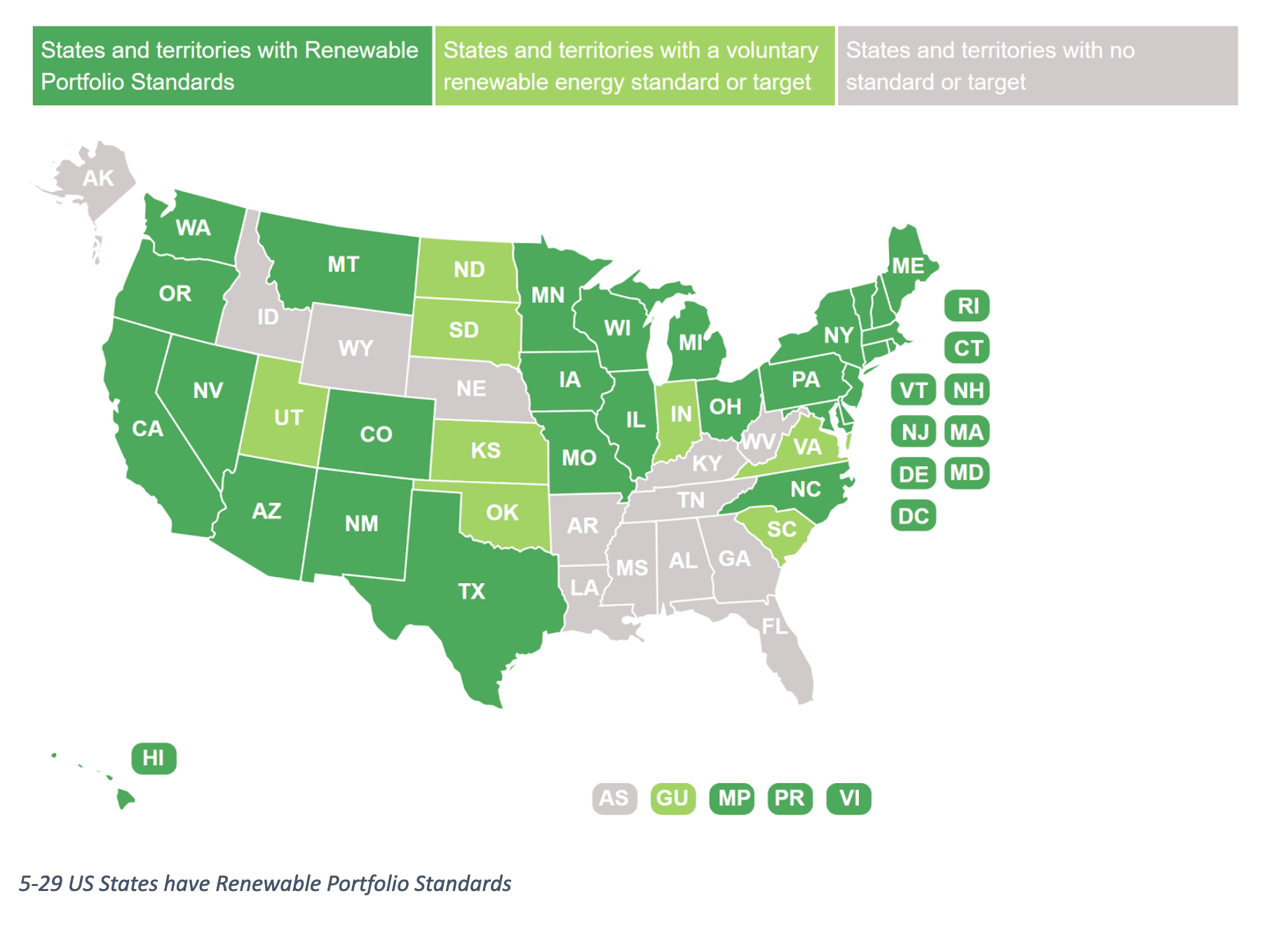

Consider, for example, that late last year, a utility in Northern Indiana announced that the cheapest way for it to provide power to its customers was to go from being 65% coal powered today, to just 15% coal powered by 2023, and zero coal by 2028 – and to replace that coal with solar, wind, batteries, and flexible storage. Let me repeat that: This utility wants to replace 50% of their power generation in just 4 years, and the rest in 5 more. And it wants to do so because solar and wind and batteries are cheaper than running their existing coal power plants. That’s a tipping point moment. And the solar and wind deployed in Indiana will lower the cost of future solar and wind deployed elsewhere. If this sort of tipping point can happen in Indiana, a deeply red state that Donald Trump won by 19 points, that isn’t all that sunny, and that has good but not amazing wind, then that tipping point can happen anywhere. Our job is to keep the pressure up. - A National Renewable Portfolio Standard. 29 US states – including red states like Texas, Missouri, Iowa, and Ohio – have Renewable Portfolio Standards that mandate that a certain percentage of their electricity must come from carbon-free or renewable sources. That means 21 states don’t have such mandates. If electricity were a perfectly competitive market, solar and wind and batteries would win on price and displace coal and gas in all these states. But utilities have a number of ways to resist change, even when it makes economic sense.

5-29 US States have Renewable Portfolio Standards

The solution is for Congress to mandate a Renewable Portfolio Standard nationally, dragging the laggard states up to the standard of the rest. How high should that mandate be? The Green New Deal goal of 100% carbon free electricity by 2030 is incredibly ambitious. And it pushes us into the unknown. Beyond 70 or 80 or 90% of electricity from renewables, integration becomes increasingly difficult as periods of bad weather nation-wide cause serious problems. The technical challenges there can be overcome – perhaps through nuclear, or next-generation carbon-capturing natural-gas plants, or long-term energy storage technologies (which are being funded by ARPA-E).

The solution is for Congress to mandate a Renewable Portfolio Standard nationally, dragging the laggard states up to the standard of the rest. How high should that mandate be? The Green New Deal goal of 100% carbon free electricity by 2030 is incredibly ambitious. And it pushes us into the unknown. Beyond 70 or 80 or 90% of electricity from renewables, integration becomes increasingly difficult as periods of bad weather nation-wide cause serious problems. The technical challenges there can be overcome – perhaps through nuclear, or next-generation carbon-capturing natural-gas plants, or long-term energy storage technologies (which are being funded by ARPA-E).

Those challenges are still real enough that even a clean energy optimist like me gets nervous. A goal of 50% of electricity from carbon free sources in every state by 2030, then 80% by 2040, and 100% by 2050 would be in-line with what scientific models say we need to achieve in order to stay below 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming. And by scaling both clean energy and the technology to integrate it to high percentages of the total grid, it would drive those technologies down in price for the rest of the world, and pave the way for cleaner grids everywhere.

- Permanent, Uncapped, On-the-Spot Electric Vehicle Tax Credit. On transportation, we may have reached another tipping point. 2018 may have been the peak year for gasoline and diesel car sales, ever. Electric Vehicles, while still small in number, are growing at an astounding rate, and account for all growth in the auto industry. In some areas, electric vehicles are now cheaper to own than gasoline cars on a per-mile basis. And that will become true in more and more areas as the price of batteries declines. Even so, we need to move faster. On average, a US car gets replaced when it’s around 10 years old. That means that, even if electric vehicles were 100% of new sales today, it would take around 20 years for them to replace all gasoline cars. That needs to happen faster. Congress can help.

First, for individually owned vehicles, Congress should improve the federal electric vehicle tax credit. Today’s $7,500 federal tax credit is capped at 200,000 electric vehicles per manufacturer. That’s an absurdly low number in a country that has 260 million cars on the road. General Motors CEO Mary Barra recently called for the cap to be removed. Congress ought to put electric vehicles on the same footing as solar, wind, and batteries: A 30% tax credit – like the solar ITC – with no limit on the number of vehicles its applied to would be simple, clear, and consistent. For individuals buying their own vehicles, that tax credit ought to be structured so it can be taken off the purchase price of the vehicle directly, rather than waiting for tax season.

Second, the same tax credit ought to apply to fleet operators who buy or build electric vehicles to offer rides to consumers. While the pace at which consumers buy new cars is slow, the pace at which they switch miles of transport can be far faster, as they switch some of their travel to fleets like Uber, Lyft, and whatever comes after. Those fleets, today, are mostly gasoline engine vehicles of hybrids. As electric vehicles increasingly become the cheapest per mile, those app-based transport fleets will go electric. And a typical taxi drives 70,000 miles a year, or roughly 4 times the 13,500 miles per year of a typical individually-owned car. That means each electric vehicle deployed as a taxi can have the impact of four individually owned vehicles.

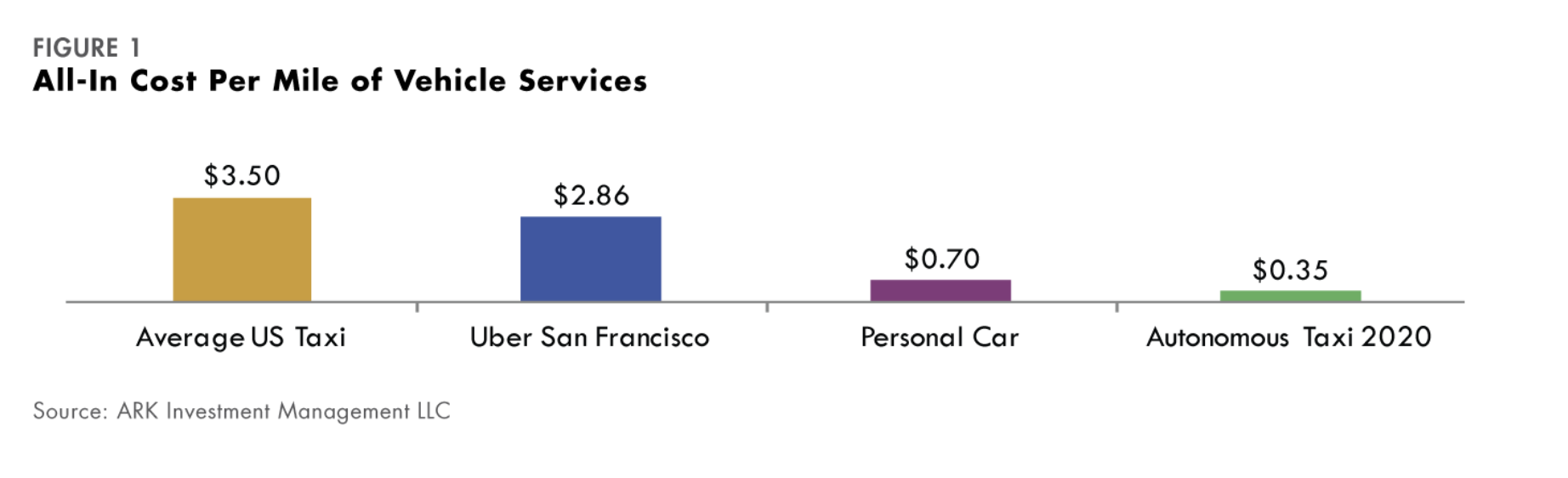

Finally, Congress ought to accelerate the deployment of autonomous cars on the nation’s roads. Why? Because an autonomous vehicle, by taking out the cost of the driver, can cut the cost per mile by half. Some calculations show that an autonomous electric taxi, by 2025, could cost 35 cents per mile. That’s 1/10th of what a taxi costs, 1/5th of what a Lyft or UberX costs today, and half the cost of owning and operating your own car. That lower cost would cause even more rapid switching to electric transport fleets, as currently-owned gasoline vehicles increasingly sat unused, or saved for long-distance trips or other scenarios. Some studies find that, even at twice that price, as much as 40% of miles driven would switch to these electric fleets.

6 – Autonomous Electric Taxis could be half the cost per mile of owning and operating a gasoline car – if autonomous vehicles arrive.

Getting to those costs absolutely depends on autonomy. Today, however, autonomous driving is regulated by a hodge-podge of different laws at the State level. Congress should step in and act to standardize safety testing, unify laws between states, and accelerate the deployment of safe, cheap, efficient, electric autonomous taxi services. Congress almost did so in 2018. It’s time to try again.

These three actions would both accelerate the deployment of electric vehicles in the US, and drive innovation in a sector where US companies are currently in the lead, and where they could be global leaders in trillion-dollar industries for decades to come.

- Incentives for EV Chargers – Everywhere. Deploying more electric vehicles also means a demand for more charging infrastructure. Congress ought to create incentives to deploy electric chargers in the places they make the most sense, and to lower the cost of charging stations by scaling them.

For individually-owned vehicles, incentives already exist to install a charger at home. But drivers who park on the street or who live in apartment buildings without charging don’t have an easy way to use a home charger. Congress ought to create federal incentives to deploy charging stations in multi-unit buildings, in malls, at grocery stores, and so on. Congress should especially create incentives for employers to deploy charging stations for their employees at work. Charging stations make the most sense in the locations that cars spend the most time in. And after home, the clear #2 for most vehicles is at work. In addition, vehicles driven to work are most likely to be idle during the day – when solar power is producing. Charing electric vehicles during the day both allows the US to put more total solar power to use (effectively storing it in these vehicles) and solves the problem of a lack of charging location for those who don’t have convenient charging at home.

Similarly, if transportation is going to move more and more to electric (possibly autonomous) taxi fleets, those vehicles will need charging too. Congress ought to create incentives for that charging infrastructure to accelerate its deployment.

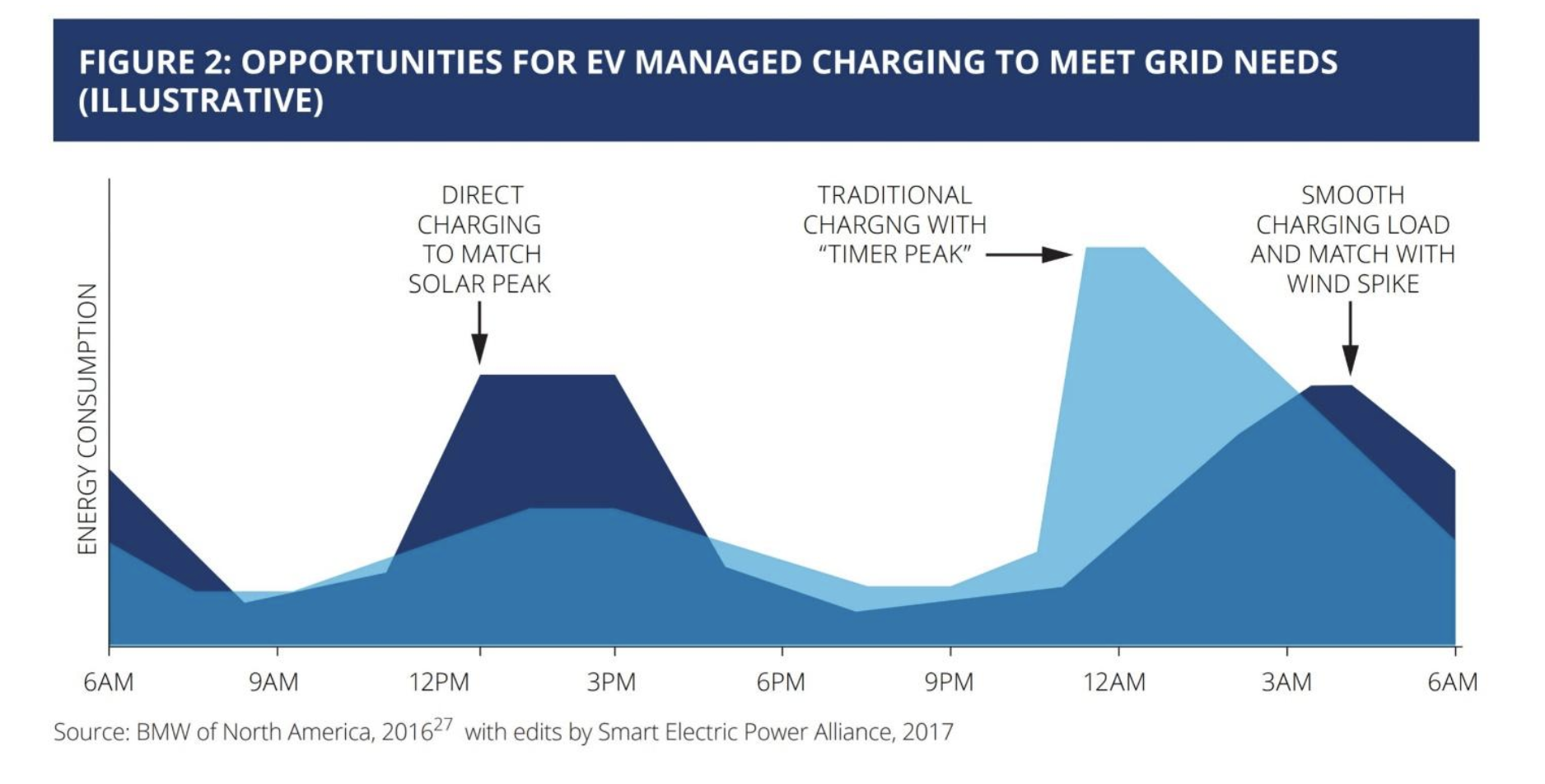

More generally a report from the Smart Electric Power Alliance finds that as electric vehicles and electric vehicle charging infrastructure spread, there’s an opportunity to use software to manage when vehicles charge, to line that charging up with both solar and with the hours of peak wind power output, allowing more renewables to be integrated onto the grid.

7 – Electric vehicles with smart chargers could charge when solar and wind are most abundant on the grid, increasing the amount of renewable energy we can use.

- Tax Credits for Carbon-Free Heating and Building Efficiency. Beyond electricity and transportation, heating buildings accounts for 6% of all carbon emissions around the world, and is growing rapidly. To decarbonize the world’s economy, we need to shift from heating with natural gas (or, in the poorest parts of the world, with coal or wood) to heating with carbon-free energy. While extending tax credits for solar and wind, Congress should keep those credits consistent for passive solar heating and geothermal heating systems, and extend those tax credits to also to include switching to an electric heat pumps, and any energy efficiency improvements made to a building.

Wait, but what about?

So I didn’t list your favorite technology, policy, or issue? Here:

- Nuclear. In 2018, the US got roughly 20% of its electricity from nuclear power, or roughly twice as much as it does from solar and wind combined. That’s carbon-free electricity from already running reactors. Shutting down those reactors prematurely would be a mistake. Germany’s shutdown of their nuclear reactors led to Germany missing their goals for carbon reduction. Existing reactors – so long as they’re safe – should be kept running as long as possible, while solar and wind scale up. And indeed, there’s still quite a bit of debate about whether solar, wind, hydro, and batteries together can power 100% of the US. Some very smart scientists who care deeply about climate are skeptical that renewables can get us all the way there. I’m on the more optimistic side of this equation. Even so, let’s not tie one hand behind our back.

New nuclear, on the other hand, is probably dead in the US and Europe. Costs are rising over time, and reactors are plagued by cost overruns and schedule delays. The US ought to continue funding research into next-generation reactors that could be built smaller, more repeatably, and hopefully one day at a lower cost. Even those reactor designs are most likely to be a fallback in case solar, wind, and batteries stop falling in price the way they have. - Carbon Taxes. I spent much of 2015 advocating for a revenue-neutral carbon tax in Washington State. I love carbon taxes. And in electricity, they can be quite powerful. As I explain elsewhere, though, outside of the electricity sector, carbon taxes are far less effective than believed. They have only a little impact on industry, almost no impact on transportation, and usually aren’t applied to agriculture. If a carbon tax magically passed Congress, I’d cheer, and it could be an effective way to fund some of the proposals here. It’s not a silver bullet, though, and it doesn’t address the hardest sectors.

- Carbon Capture. People mean a wide variety of things when they say “carbon capture”. If we mean retrofitting coal power plants with equipment to capture their carbon emissions and store it, that’s probably a waste of time. Coal is economically dead, even before adding on the cost of carbon capture. On the other hand, the NetPower design for an advanced natural gas plant that has carbon capture built right in could be a great complement to solar and wind, filling in for them during wind droughts in winter. (Though keeping any sort of natural gas in use also requires that we address the serious problem of methane leaks from natural gas wells and infrastructure.)

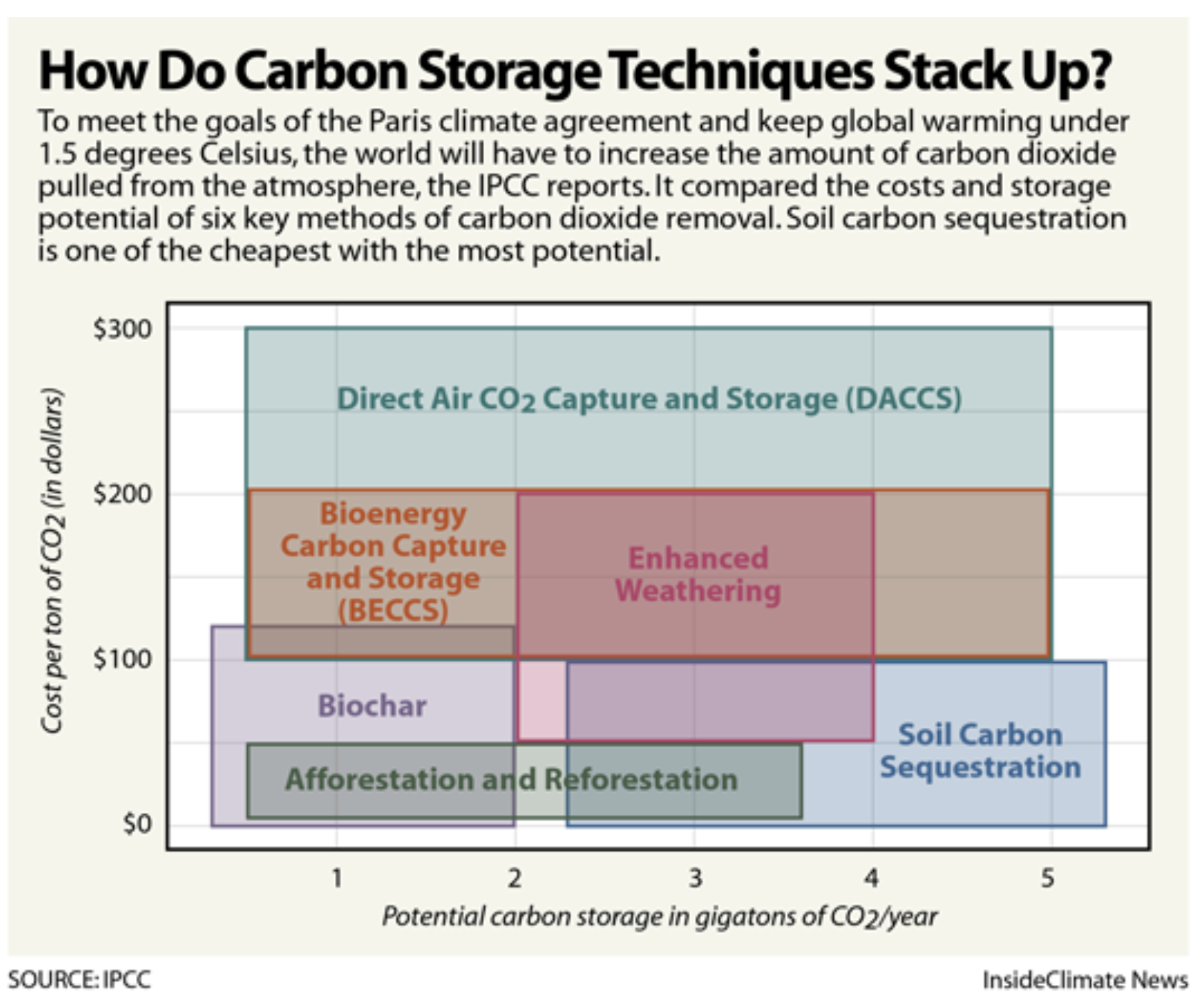

The most important type of carbon capture, though, is being able to capture carbon directly from the air. I support more R&D into high-tech ways to scrub carbon from the air. I’m also cheered to see the tax credit Congress created to encourage carbon capture. That said, overwhelmingly the most affordable ways to capture carbon, today, are the ones the Green New Deal talks about: returning carbon to the natural environment, by enriching soils and planting trees. Enriching farm soils and planting trees cost ten times less than fancier methods of carbon capture, and could capture a billion tons of carbon a year in the US alone. What’s more, the US could make those methods even cheaper by spurring new technology – like tree-planting drones, or transparent digital markets for carbon capture – in a way that increases the adoption of carbon capture into natural ecosystems around the world. Ultimately, we may need to draw even more carbon out of the air than soils and trees can handle. We should do the R&D for higher tech methods that can do so, and encourage their deployment, even as we use the cheapest methods of soils and forests first.

8 – The cheapest ways to capture carbon are on the bottom of this chart – in soils and forests.

What About Climate Justice?

The Green New Deal advances a plan to fight climate change and to ensure that we do so through a just transition. Here, I think a few principles clearly apply.

- First, the cost of the transition shouldn’t be paid by those with the lowest income or who’ve contributed the least to the problem. In the long term, transitioning to a clean economy will make energy, transportation, and the rest of the goods we consume cheaper. If, in the short run, (when we’re using subsidies to scale out new technologies to drive their costs down) there’s any temporary increase in the cost of life’s necessities, that shouldn’t be passed on to low-income Americans. If costs for basic necessities go up, that needs to be offset by policies that buffer lower-income Americans against those changes.

- Second, if we need new taxes to pay for these programs, those taxes should be highly progressive. If those taxes are on income, they should come in at the higher tax brackets. This also has to inform our view of a carbon tax. Carbon taxes are, on their own, highly regressive. Lower-income Americans spend a larger fraction of their paycheck on electricity, heating, transportation, and other carbon-intensive goods than wealthier Americans do. Rural Americans, who also tend to be lower income and who have the highest rates of poverty in America, spend even more of their paycheck on transportation. So raising the price of energy, transportation, and other goods hits low-income Americans and rural Americans the hardest. If we use a carbon tax, we can offset it by sending a flat dividend check to every woman, man, and child in America. In Washington State, in our 2016 ballot initiative, we used another approach, using carbon tax revenue to boost the federal Earned Income Tax Credit – a tax credit that goes to low-income working families, and which is the closest thing to a basic income we have now.

- Third, we need to help Americans in the most vulnerable communities with climate resistance and climate adaptation. Whether those are communities that are vulnerable to climate-related flooding, crop losses from extreme weather, heat and drought, or to wildfires that will get worse as temperatures rise, society ought to invest in boosting the resilience of these communities, and, if necessary, in helping individuals and communities relocate to areas that are less vulnerable to climate.

- Fourth, massive investment in new clean energy, industry, transportation, and agriculture will pour trillions into the US economy. What’s more, it has the potential to turn the US into an exporter of new clean technology. Together, they’ll create the opportunity for potentially millions of new jobs. That opportunity ought to be open to all – to workers in dirty industries like coal who have their jobs displaced, to lower income Americans who have fewer opportunities today, and to immigrants willing to come to America and work. Job training programs, and programs to bridge the gap between the end of an old career and the start of a new one – are a win/win for America. They help us produce the labor pool to transition to this clean economy, and they provide a means for millions of Americans to uplift themselves with new, highly in-demand skills.

All of that is fully in alignment with the Green New Deal resolution. The GND goes further, though, making the case for universal healthcare, universal higher education, universal housing, a job guarantee for all people in the United States, strengthening unions, reducing discrimination in the workplace, respect for Native American rights and sovereignty, and stopping the transfer of jobs overseas.

Many of those policies are ones I support, or at least where I support the motivations behind them. Yet I am not at all certain those policies should be coupled with climate action. Coupling a long list of liberal priorities with climate action would seem to make it harder to get the bipartisan support we’ll probably need to enact these climate policies. That said, the Green New Deal resolution is a high level map, not a specific bill. The original New Deal wasn’t one piece of legislation – it was made up of more than 30 separate bills. Democrats should approach the Green New Deal the same way. They ought to embrace the idea that the overall effort may take multiple years and multiple Congresses to enact, and that it’s perfectly acceptable to support some parts of the Green New Deal and not others. They ought to embrace alliances and assistance – including bipartisan alliances – to pass parts of the Green New Deal where they can.

(Photo by Ira L. Black/Corbis via Getty Images)

Climate Action is the Ultimate Climate Justice

Even more importantly, though, acting on climate change itself creates a more just world. Climate change is a slow, insidious, and massive threat to human well-being. It’s also profoundly unjust. Americans may only emit 15% of carbon emissions today, but all the CO2 we’ve emitted in the past will linger in the atmosphere for roughly a century from when it was released. Add up all the carbon the US has emitted over time, and the US remains the largest cumulative emitter of greenhouse gases on the planet. We Americans are more responsible for climate change than any other nation, even those with many times our population.

Meanwhile, two billion people live in countries that have emitted the least carbon dioxide over history – the poorest countries on planet earth – which are also the countries where people are likely to suffer the most from climate change. Climate change itself is a deep inequity. The most just thing we can do is to address climate change as rapidly as possible, and to produce and spread the tools that also boost climate resilience around the developing world. Indeed, most of the benefits of fighting climate change don’t go to Americans at all. Americans do benefit. But the largest benefits of fighting climate change go to the billions around the world who have the fewest resources and who live in the nations with the greatest vulnerability.

Lower income Americans also stand to suffer more from climate change than do wealthier Americans. A lower-income American in Detroit isn’t as vulnerable as a subsistence farmer in Botswana – not by a long shot. At the same time, it’s hard to deny that Katrina, for example, hit the poor of New Orleans harder than it did the rich. Wealthier Americans can relocate more easily, can pay energy bills more easily, can rebuild from climate disasters more easily. And here again, the most just thing we can do is to act on climate, as rapidly as possible.

Should we find ways to use the fight against climate change to also address the long history of inequality and injustice, and the differences in wealth and income that exist in the US? If so, should we stop there? Climate change is global. Carbon emissions and the harm they cause know no national borders. The harm of American (and European, and more recently Chinese) carbon emissions will fall most heavily on the poor of the developing world. Should climate policy aim to decarbonize the world as rapidly as possible? Or should it aim to decarbonize and address other global ills?

For me, the answer is clear. Climate change itself is so unjust, so lopsided in who has benefited from burning fossil fuels and who will suffer the most from that combustion, that addressing climate change is, itself, to help undo an injustice – one that threatens billions of people around the world.

Let’s tackle all the world’s other problems too. As we do so, let’s keep in mind that addressing climate change, even if we don’t succeed at everything else, is a major, vital, and necessary step towards a more just world.

Powered by WPeMatico