WhatsApp has an encrypted child porn problem

WhatsApp chat groups are being used to spread illegal child pornography, cloaked by the app’s end-to-end encryption. Without the necessary number of human moderators, the disturbing content is slipping by WhatsApp’s automated systems. A report from two Israeli NGOs reviewed by TechCrunch details how third-party apps for discovering WhatsApp groups include “Adult” sections that offer invite links to join rings of users trading images of child exploitation. TechCrunch has reviewed materials showing many of these groups are currently active.

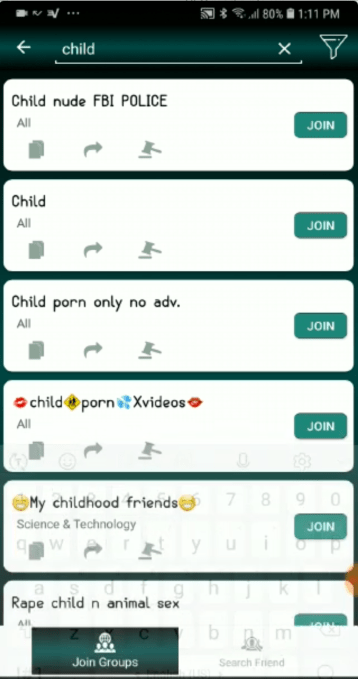

TechCrunch’s investigation shows that Facebook could do more to police WhatsApp and remove this kind of content. Even without technical solutions that would require a weakening of encryption, WhatsApp’s moderators should have been able to find these groups and put a stop to them. Groups with names like “child porn only no adv” and “child porn xvideos” found on the group discovery app “Group Links For Whats” by Lisa Studio don’t even attempt to hide their nature. And a screenshot provided by anti-exploitation startup AntiToxin reveals active WhatsApp groups with names like “Children

” or “videos cp” — a known abbreviation for ‘child pornography’.

” or “videos cp” — a known abbreviation for ‘child pornography’.

A screenshot from today of active child exploitation groups on WhatsApp. Phone numbers and photos redacted. Provided by AntiToxin.

Better manual investigation of these group discovery apps and WhatsApp itself should have immediately led these groups to be deleted and their members banned. While Facebook doubled its moderation staff from 10,000 to 20,000 in 2018 to crack down on election interference, bullying and other policy violations, that staff does not moderate WhatsApp content. With just 300 employees, WhatsApp runs semi-independently, and the company confirms it handles its own moderation efforts. That’s proving inadequate for policing a 1.5 billion-user community.

The findings from the NGOs Screen Savers and Netivei Reshe were written about today by Financial Times, but TechCrunch is publishing the full report, their translated letter to Facebook, translated emails with Facebook, their police report, plus the names of child pornography groups on WhatsApp and group discovery apps listed above. A startup called AntiToxin Technologies that researches the topic has backed up the report, providing the screenshot above and saying it’s identified more than 1,300 videos and photographs of minors involved in sexual acts on WhatsApp groups. Given that Tumblr’s app was recently temporarily removed from the Apple App Store for allegedly harboring child pornography, we’ve asked Apple if it will temporarily suspend WhatsApp, but have not heard back.

Uncovering a nightmare

In July 2018, the NGOs became aware of the issue after a man reported to one of their hotlines that he’d seen hardcore pornography on WhatsApp. In October, they spent 20 days cataloging more than 10 of the child pornography groups, their content and the apps that allow people to find them.

The NGOs began contacting Facebook’s head of Policy, Jordana Cutler, starting September 4th. They requested a meeting four times to discuss their findings. Cutler asked for email evidence but did not agree to a meeting, instead following Israeli law enforcement’s guidance to instruct researchers to contact the authorities. The NGO reported their findings to Israeli police but declined to provide Facebook with their research. WhatsApp only received their report and the screenshot of active child pornography groups today from TechCrunch.

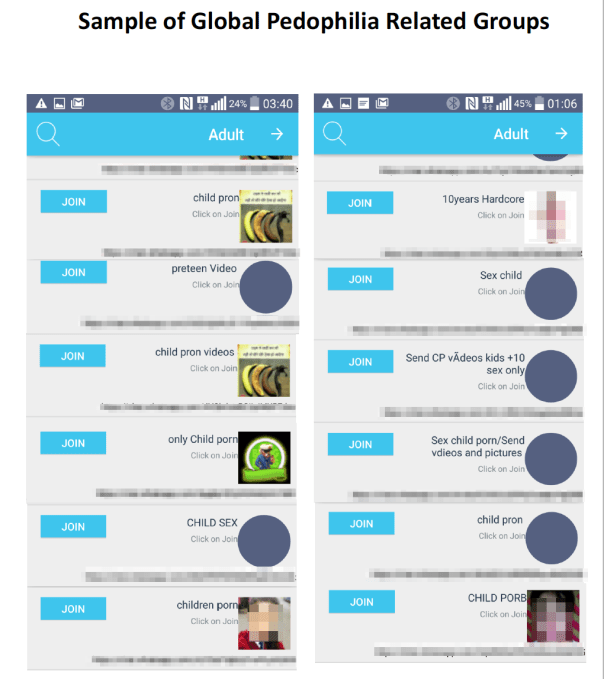

Listings from a group discovery app of child exploitation groups on WhatsApp. URLs and photos have been redacted.

WhatsApp tells me it’s now investigating the groups visible from the research we provided. A Facebook spokesperson tells TechCrunch, “Keeping people safe on Facebook is fundamental to the work of our teams around the world. We offered to work together with police in Israel to launch an investigation to stop this abuse.” A statement from the Israeli Police’s head of the Child Online Protection Bureau, Meir Hayoun, notes that: “In past meetings with Jordana, I instructed her to always tell anyone who wanted to report any pedophile content to contact the Israeli police to report a complaint.”

A WhatsApp spokesperson tells me that while legal adult pornography is allowed on WhatsApp, it banned 130,000 accounts in a recent 10-day period for violating its policies against child exploitation. In a statement, WhatsApp wrote that:

WhatsApp has a zero-tolerance policy around child sexual abuse. We deploy our most advanced technology, including artificial intelligence, to scan profile photos and images in reported content, and actively ban accounts suspected of sharing this vile content. We also respond to law enforcement requests around the world and immediately report abuse to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Sadly, because both app stores and communications services are being misused to spread abusive content, technology companies must work together to stop it.

But it’s that over-reliance on technology and subsequent under-staffing that seems to have allowed the problem to fester. AntiToxin’s CEO Zohar Levkovitz tells me, “Can it be argued that Facebook has unwittingly growth-hacked pedophilia? Yes. As parents and tech executives we cannot remain complacent to that.”

Automated moderation doesn’t cut it

WhatsApp introduced an invite link feature for groups in late 2016, making it much easier to discover and join groups without knowing any members. Competitors like Telegram had benefited as engagement in their public group chats rose. WhatsApp likely saw group invite links as an opportunity for growth, but didn’t allocate enough resources to monitor groups of strangers assembling around different topics. Apps sprung up to allow people to browse different groups by category. Some usage of these apps is legitimate, as people seek communities to discuss sports or entertainment. But many of these apps now feature “Adult” sections that can include invite links to both legal pornography-sharing groups as well as illegal child exploitation content.

A WhatsApp spokesperson tells me that it scans all unencrypted information on its network — basically anything outside of chat threads themselves — including user profile photos, group profile photos and group information. It seeks to match content against the PhotoDNA banks of indexed child pornography that many tech companies use to identify previously reported inappropriate imagery. If it finds a match, that account, or that group and all of its members, receive a lifetime ban from WhatsApp.

A WhatsApp group discovery app’s listings of child exploitation groups on WhatsApp

If imagery doesn’t match the database but is suspected of showing child exploitation, it’s manually reviewed. If found to be illegal, WhatsApp bans the accounts and/or groups, prevents it from being uploaded in the future and reports the content and accounts to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. The one example group reported to WhatsApp by Financial Times was already flagged for human review by its automated system, and was then banned along with all 256 members.

To discourage abuse, WhatsApp says it limits groups to 256 members and purposefully does not provide a search function for people or groups within its app. It does not encourage the publication of group invite links and the vast majority of groups have six or fewer members. It’s already working with Google and Apple to enforce its terms of service against apps like the child exploitation group discovery apps that abuse WhatsApp. Those kind of groups already can’t be found in Apple’s App Store, but remain available on Google Play. We’ve contacted Google Play to ask how it addresses illegal content discovery apps and whether Group Links For Whats by Lisa Studio will remain available, and will update if we hear back. [Update 3pm PT: Google has not provided a comment but the Group Links For Whats app by Lisa Studio has been removed from Google Play. That’s a step in the right direction.]

But the larger question is that if WhatsApp was already aware of these group discovery apps, why wasn’t it using them to track down and ban groups that violate its policies. A spokesperson claimed that group names with “CP” or other indicators of child exploitation are some of the signals it uses to hunt these groups, and that names in group discovery apps don’t necessarily correlate to the group names on WhatsApp. But TechCrunch then provided a screenshot showing active groups within WhatsApp as of this morning, with names like “Children

” or “videos cp”. That shows that WhatsApp’s automated systems and lean staff are not enough to prevent the spread of illegal imagery.

” or “videos cp”. That shows that WhatsApp’s automated systems and lean staff are not enough to prevent the spread of illegal imagery.

The situation also raises questions about the trade-offs of encryption as some governments like Australia seek to prevent its usage by messaging apps. The technology can protect free speech, improve the safety of political dissidents and prevent censorship by both governments and tech platforms. However, it also can make detecting crime more difficult, exacerbating the harm caused to victims.

WhatsApp’s spokesperson tells me that it stands behind strong end-to-end encryption that protects conversations with loved ones, doctors and more. They said there are plenty of good reasons for end-to-end encryption and it will continue to support it. Changing that in any way, even to aid catching those that exploit children, would require a significant change to the privacy guarantees it’s given users. They suggested that on-device scanning for illegal content would have to be implemented by phone makers to prevent its spread without hampering encryption.

But for now, WhatsApp needs more human moderators willing to use proactive and unscalable manual investigation to address its child pornography problem. With Facebook earning billions in profit per quarter and staffing up its own moderation ranks, there’s no reason WhatsApp’s supposed autonomy should prevent it from applying adequate resources to the issue. WhatsApp sought to grow through big public groups, but failed to implement the necessary precautions to ensure they didn’t become havens for child exploitation. Tech companies like WhatsApp need to stop assuming cheap and efficient technological solutions are sufficient. If they want to make money off huge user bases, they must be willing to pay to protect and police them.

Powered by WPeMatico